On August 2, 2017, US President Donald J. Trump signed into law H.R.3364, a new set of economic sanctions aimed primarily on Russia (with additional measures adopted against Iran and North Korea). Essential to the success of any sanctions regime is its alignment. As defined by John Forrer in an upcoming paper, economic sanctions are aligned when they “inflict a prescribed amount of economic loss… at a level to achieve the identified foreign policy goal(s) with the least amount of unwanted harm.”

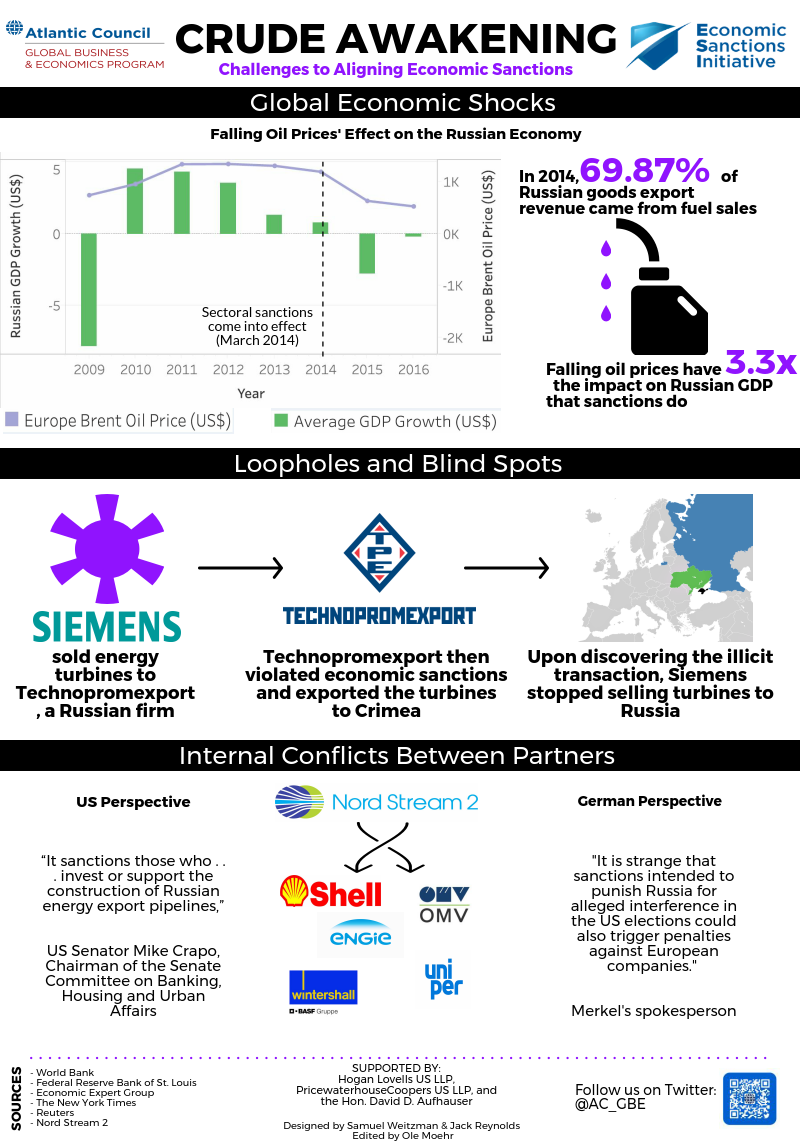

As demonstrated by previous measures imposed by the United States and the European Union (EU) against Russia, attempts to align sanctions face several major challenges. To begin with, economic sanctions often fail to account for potential economic and political shifts at the regional and global levels, resulting in higher or lower costs than originally intended. In the case of Russia, the sanctions coincided with the global collapse of oil prices, upon which much of the Russian economy depends. In turn, the combination of sanctions and low oil prices has led the Russian government to slash social spending while protecting allies of the Kremlin, to the detriment of much of the population. These impacts indicate that sanctions against Russia—which were intended “to influence Russian decision-making” by targeting allies of Russian President Vladimir Putin—were improperly calibrated when confronted with the falling price of oil.

Another problem for sanctions alignment is that they are rarely (if ever) inviolable, thus allowing some actors to take advantage of loopholes and blind spots in sanctions enforcement. The recent discovery of smuggled Siemens turbines in Crimea—in violation of existing sanctions—demonstrates the ease with which many individuals and firms are able to evade the reach of sanctions.

Furthermore, the multilateral nature of many sanctions regimes means that differences in priorities can generate friction among partners. Before the US Congress passed the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, European countries, in particular Germany, voiced concerns over the implications of H.R.3364 for the Nord Stream 2 project. The proposed twin pipeline, roughly 750 miles in length, would enable Russia to bypass Ukraine when delivering natural gas to Germany, thereby depriving Kiev of $2 billion in annual transit fees. The German government argued that the new US sanctions could punish German firms who violate H.R.3364’s section 232, which prohibits assisting in “the construction of Russian energy export pipelines.” The United States and many Central and Eastern European countries—particularly Poland and the Baltic States—contend that Nord Stream 2 would grant Moscow additional political leverage and undermine European solidarity with Ukraine. US lawmakers eventually relented by adding an instruction for the executive branch to coordinate with allies before implementing H.R.3365’s section 232. Nonetheless, these types of disagreements can imperil partnerships that are essential to current and future multilateral sanctions.

In contrast to the restrictions against Iran—which contributed to Tehran’s decision to abandon its nuclear program—it remains unclear whether sanctions against Russia have altered the Kremlin’s strategic calculus. If the United States and its European allies wish to achieve their political objectives, they must ensure the alignment of current and future sanctions.

Stay tuned for more on the topic of sanctions alignment with an upcoming issue brief by our nonresident senior fellow, Professor John Forrer.