At this year’s G20 summit in Buenos Aires, the trade dispute between China and the United States took center stage. Chinese President Xi and his US counterpart President Donald Trump agreed to avoid further escalations of the ongoing bilateral trade war for the next 90 days. The temporary deal does not assuage the escalatory measures already taken, leaving the existing tariffs in place. This edition of the EconoGraphic explores how the brewing trade conflict is impacting manufacturing supply chains, soybean cargo routes, and trade flows of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) among the United States, China, and the rest of the world.

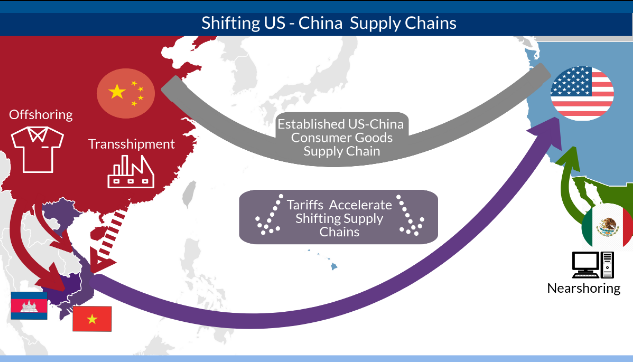

The US-China trade war is adding pressure on Chinese and foreign companies that were already facing rising costs of manufacturing consumer goods on China’s mainland before the trade tit-for-tat broke out. In turn, the reciprocal Chinese and US tariffs are bolstering a steady stream of companies that are shifting production of “electronics, apparel, household items, and other products” away from China to lower-cost destinations in Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. To avoid the tariffs, consumer goods manufacturers are also engaging in nearshoring by shifting their supply chains to countries such as Mexico and Slovakia. Unsurprisingly, there is no evidence that a significant number of companies are moving production to the United States. To protect margins without having to adjust supply chains, some Chinese factories are evading the tariffs by shipping their US-bound products, such as honey or plywood, to neighboring countries including Vietnam. Once the goods arrive in Vietnam, they are relabeled as Vietnamese exports and sent to the United States.

The Chinese tariffs on US soybeans, which Beijing imposed in July of 2018, are having a severe impact on soybeans trade flows around the world. According to recent estimates, total US soybean exports have plunged by 41 percent in the months of September and October compared to the previous year. During that period, US exports to China have fallen off a cliff, dropping by 96 percent year-over-year. At the same time, US soybean trade with the rest of the world has increased by 86 percent compared to 2017. China accounts for 60 percent of global soybean imports. This dominant market position compelled US exporters to lower their soybean prices to offset the Chinese tariff. In turn, countries in Europe and the Middle East, which traditionally imported most of their soybeans from South America, have significantly upped their purchases of US soybeans. For instance, US soybean exports to the European Union increased three-fold during the months of September and October compared to 2017. This changing trade pattern is partly the result of Brazilian soybeans trading at premium compared to the US. Brazil, which is the world’s largest soybean supplier, has increased its shipments to China to fill the large void left by missing US soybean exports. Chinese soybean demand is so strong that Brazil is taking advantage of lower US soybean prices by importing the US product to free up additional capacity for exports to China.

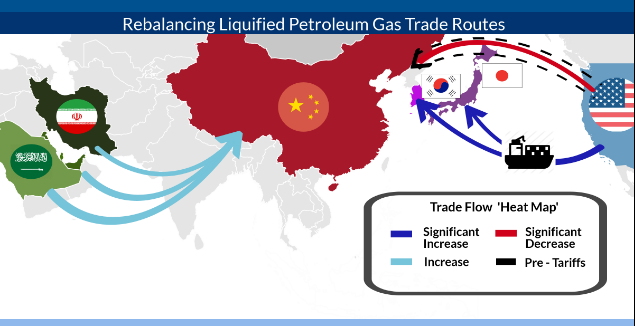

US exporters of LPG, which is a byproduct of natural gas processing and oil refining, belong to another industry that had to find new customers following the imposition of Chinese tariffs. In 2017, the US was the second largest exporter of LPG to China, contributing 20 percent or almost 3.6 million tons to China’s imports. With the threat of tariffs looming, US LPG exports to China dropped by 41 percent over the first ten months of 2018. After the Chinese government imposed tariffs on LPG in late August, US exports stopped almost completely. In contrast to the US soybean trade, Chinese buyers are not cornering the global LPG market. This contributed to total US LPG exports and prices staying stable over the course of 2018. Strong demand in Japan and South Korea is allowing US companies to shift a large fraction of LPG cargoes originally intended for China to those two countries. Meanwhile, Chinese businesses are replacing US imports with additional shipments from Iran, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait.

The examples of consumer goods manufacturers in China as well as US soybean and LPG exporters underscore how the China-US trade war is disrupting global cargo routes. The resulting economic inefficiencies create winners and losers but are harming the global economy overall. We consider the G20 trade truce between Presidents Trump and Xi as an acknowledgement of the enormous costs the trade war is imposing on both economies. Nonetheless, we remain skeptical that US negotiators and their Chinese counterparts can make meaningful progress on thorny issues, such as forced technology transfer and intellectual property protection, within the 90-day deadline. In short, even greater disruption of global trade flows continues to be a distinct possibility.

Ole Moehr is an Assistant Director at the Atlantic Council’s Global Business & Economics Program.