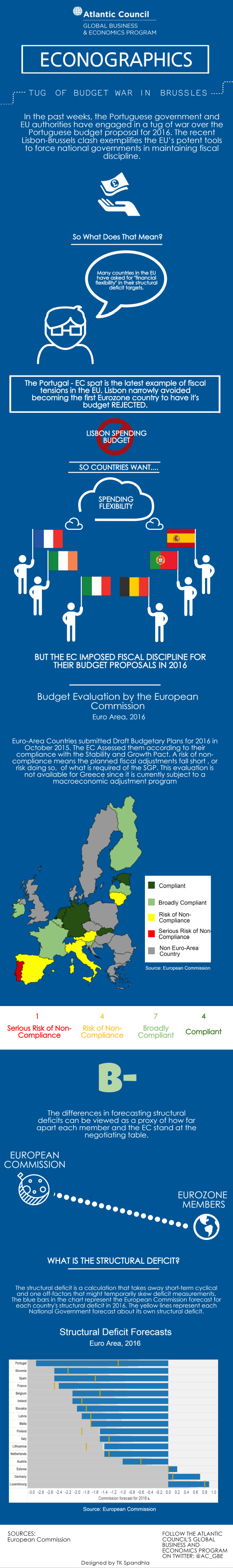

In the past weeks, the Portuguese government and EU authorities have engaged in a tug of war over the Portuguese budget proposal for 2016. The European Commission (EC) warned the newly elected anti-austerity government that it risked “serious non-compliance” with the EU’s fiscal rules. Finally, Lisbon narrowly avoided becoming the first Eurozone country to have its budget rejected by Brussels, as it agreed to additional tax hikes and spending cuts.

The Lisbon-Brussels clash exemplifies the EU’s potent tools to force national governments in maintaining fiscal discipline. It also sets a precedent for countries like Italy or Spain that have repeatedly asked for more “flexibility” in their structural deficit targets. In this context, it is worth examining the 2016 fiscal forecasts by national governments and the EC. Particularly interesting is the structural deficit, which takes away short-term cyclical and one off-factors that might temporarily skew deficit measurements. The differences in forecasting structural deficits can be viewed as a proxy of how far apart each member and the EU stand at the negotiating table. Another way to think about how much flexibility a country might have when negotiating its budget is by looking at the assessment of its budget proposal. The EC evaluates all member state’s budget proposals according to their compliance with the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP).