In theory, the Conservative party’s resounding victory at the end of last year should be positive for the United Kingdom’s (UK) fracking industry. A pro-business party ushering in a Brexit that could see European Union (EU) regulations on fracking reduced would normally suggest a boon for an industry once lauded by the Conservatives as a high priority.

Yet, in their pre-election manifesto, the Conservatives stated that their stance will be to “not support fracking unless the science shows categorically it can be done safely.” The manifesto pledge follows a government decision on November 2 to place a moratorium on fracking operations and an announcement that they will not move forward any proposed planning reforms for shale gas developments. The suspension was a result of the government’s Oil and Gas Authority publishing a report that concludes it is not currently possible to accurately predict the probability or magnitude of earthquakes linked to fracking operations.

Such a position is seemingly something of a U-turn for the party, which has attempted to support the industry for nearly the last decade of political power. David Cameron, then prime minister, stated in 2014 that his government was “going all out for shale” and the Tories reportedly attempted to fast track and prioritise requests for fracking from Cuadrilla Resources, the only company to have had active drilling in the country.

Why adopt such a significant policy change now? There appear to be two main reasons.

First, the industry has faced a series of legal and regulatory challenges that has slowed development and exploitation. This was not, in fact, the first moratorium placed on fracking in the UK and, as such, Cuadrilla has struggled for eight years to develop commercial sites. After being granted an exploration and development licence along the coast of Lancashire for shale gas exploration, fracking began in March 2011 but was halted in May of that same year following two seismic events measuring magnitude 2.3 and 1.4 in the area. The government responded by placing a moratorium on fracking nationwide. Although rescinded in December 2012, it was not until October 2018 that fracking resumed in a new site, following a series of legal challenges. Two months later, fracking paused again following a 1.5 magnitude tremor. Finally, the resumption of fracking in August 2019 was followed by the recent indefinite suspension in November by the government following three more seismic events. At the time of the moratorium in November, there was only one active fracking site in the UK, Cuadrilla’s Preston New Road site in Lancashire.

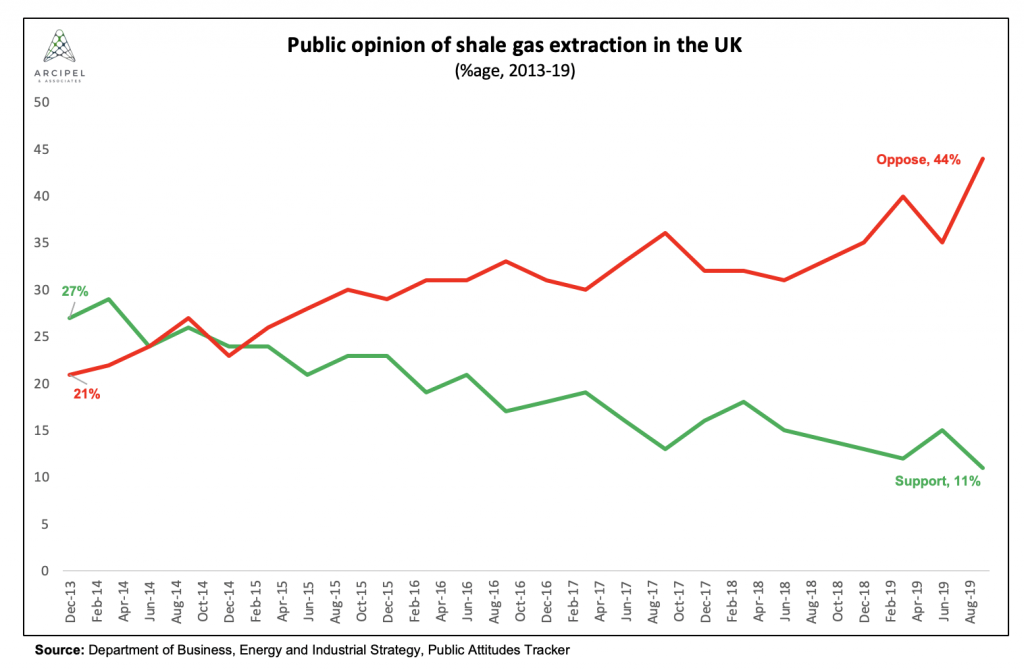

Second, and as a consequence of the first, there has been consistent opposition from environmental groups and worsening public opinion. The government’s own polling showed that public opinion was mildly in favour of fracking six years ago—by 27 percent to 21 percent. By the latest polling in September 2019, that support had flipped to broad opposition with 44 percent opposed and just 11 percent supporting fracking.

For a government heading into an election, a suspension of fracking seemed like a smart political move. The decision would seem to accord with the general public’s opinion, and in the county where the fracking has most recently taken place, the Conservatives gained three seats, holding eleven out of sixteen total. Although it is impossible to assign these victories to local issues such as fracking, for candidates campaigning in Lancashire it dulled potentially thorny attacks by Labour candidates.

This then raises the question: was the suspension of fracking a mere temporary political gambit focused purely on the election, or is it indicative of a deeper challenge for the industry? The fact that both the government and the opposition both promised at least a temporary ban on fracking suggests broad societal discontent with the industry, while the specific geology of the UK could make fracking under current techniques untenable.

Yet, the Tories have left the door open to a resumption of fracking in the future. The recent moratorium was enforced until “compelling new evidence” showed that it was safe, meaning it was not an indefinite ban. Moreover, even while announcing the moratorium in early November, Business Secretary Andrea Leadsom noted that the industry remained a “huge opportunity” if the gas could be extracted safely, underlining a continued desire within the government to develop a potentially lucrative and strategic industry.

The government is no doubt aware that fracking could boost energy security for the UK by providing an alternative domestic source of energy production. Further, the industry could assist in reducing demand for higher-emission energy sources, such as coal and oil, and thus help reach the government’s own goal of net-zero emissions by 2050.

Nevertheless, with such stringent public opposition, it may take new techniques or data before even a Conservative government relents and lets fracking proceed.

Christian Le Miere is the founder of Arcipel, a strategic advisory firm delivering predictive insight, project implementation and communications support to organisations worldwide.

Image: The UK Parliament and Big Ben in London. Photo by Unsplash/Heidi Fin