Note: This blog is the third in a series examining the global energy transition through the lens of communities with a significant stake in the traditional energy economy. In examining the social, political, and economic dynamics, policy choices that are made or missed, and the approaches that seem most promising and scalable, there is the possibility of strengthening social cohesion and equitable outcomes amid the global energy transition.

Kentucky has been hit hard by recent trends in energy markets, particularly the downturn in the fortunes of coal. Beyond the trends, it has also been deprived of some of the positive policy architectures that helped to buttress San Joaquin Valley.

Many of those affected in Kentucky attribute the decline of coal to federal environmental regulations being imposed on the state. This was crystallized by Senator Mitch McConnell’s assertion that the goal of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) “is not to see the Kentucky coal industry comply with its boatload of regulations and red tape. It is to see the Kentucky coal industry driven out of business altogether.” In response to the Clean Power Plan, a federal plan to regulate greenhouse gas emissions announced by the EPA in 2014, McConnell argued that the “regulation seeks to shut down more of America’s power generation under the guise of protecting the climate.” This rhetoric by officials has, in turn, contributed to an attitude of skepticism, at times even resentment, towards renewables.

Although the Supreme Court halted implementation of the Clean Power Plan in 2016, coal has not seen a comeback. Recent analysis indicates that competition from falling natural gas prices is responsible for 49 percent of the recent decline in US coal production, while lower-than-expected demand is responsible for 26 percent and growth in renewable energy is responsible for only 18 percent. Over a longer period, a number of other factors have contributed, most notably regional competition between coal production centers in the west—Wyoming, for example—and those in the east, driven in turn by railroad deregulation and faster productivity gains in Western coal extraction.

Policies aimed at driving Eastern Kentucky economic growth have yielded questionable results. The state of Kentucky collects a severance tax on coal as it is removed from the ground, and while the state keeps most of the revenue in a general fund, coal-producing counties are assumed to get a proportional share to help diversify their economies. However, this money has not always seen its way directly to in-need coal communities. In 2013, $2.5 million was diverted toward renovating a University of Kentucky sports facility, Rupp Arena, with the promise of repayment. Although there was a large surplus of funds for the project, repayment was never initiated until a failed attempt to get state funding for a much larger expansion of the arena and convention center in 2016.

Recently, Kentucky has improved its allocation of funds toward coal counties, with about half of coal severance tax dollars directed toward water and sewer projects, development of industrial sites, and education and social programs. Although more money is being funneled to in-need communities, plummeting coal production makes the revenue unreliable. In 2011, the tax revenue was $20.5 million, compared to $8.9 million in 2016.

Looking ahead, little relief appears to be in sight for coal, as US production is projected to decline through 2040. In a best-case scenario, US coal production will experience a modest recovery to 2013 levels, under 1 billion tons per year. In a worst-case scenario, it could fall to 600 million tons.

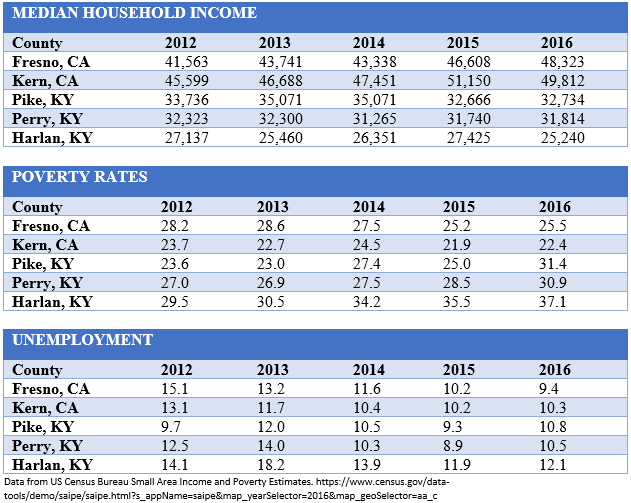

Five of the ten poorest countries in the United States run in a line through Eastern Kentucky and 64 percent of those employed by coal in Kentucky lost their jobs between 2011-2016, the worst job loss in the nation. New technologies mean that fewer people are needed to maintain the same level of coal production, so even if production stays stable, coal employment is unlikely to expand. Employers in Eastern Kentucky would need to hire around 30,000 people to move counties out of economically distressed status. This number will only increase if not quickly acted upon, due to rising layoffs in the coal industry. With clean energy creating jobs at a 12 times faster rate than the rest of the US economy, there may be opportunities to fill unemployment by embracing these technologies locally.

The political climate may be shifting toward a transition for Kentucky. In January 2018, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) denied US Secretary of Energy Rick Perry’s request to subsidize coal and nuclear plants. When asked his views on the future of the US electricity sector, President Trump’s own appointed FERC commissioner simply stated: “renewables, renewables, renewables.” Due to an increasingly apparent bleak future for coal, McConnell has recently dialed down his rhetoric, cautioning that ending the “war on coal” may not bring jobs back to Kentucky.

Under its current policy environment, Kentucky has the second worst rate of return for solar investments in the country. To support a transition, Kentucky could consider a renewable portfolio standard (RPS), a state-wide policy that mandates a certain share of renewables. Thirty-eight states currently have an RPS. Renewable energy comprised 2.23 percent of Kentucky’s total energy production in 2010 and 4.34 percent in 2015, with virtually zero produced in Eastern Kentucky. A study by the Mountain Association for Community Economic Development and the Kentucky Sustainable Energy Alliance in 2012 projected the net incremental impacts of an RPS: an increase personal income by nearly $1 billion, Gross State Product by $1.5 billion, and jobs by 120,140 by 2022.

It is not the resources limiting renewable energy expansion in Kentucky, but instead the policies. New York, North Carolina, and Ohio have similar levels of sun and are implementing effective solar solutions. According to solar power potential rankings based off sun index, Kentucky ties with New York at eighteenth, North Carolina twelfth, and Ohio twenty-third. Although Kentucky has ample solar potential, it is restrained structurally, ranking forty-eighth in terms of solar friendly policies (the aforementioned states all rank above thirty).

Although the state government has not moved forward with renewables, private entities are largely seizing their favorable economics. East Kentucky Power Cooperative is currently installing 32,000 solar panels after previously being more than 90 percent reliant on coal power . Last month, L’Oreal USA announced plans to purchase 40 percent of the renewable natural gas to be produced at a landfill-gas project being developed in Ashland, Kentucky. The project will help L’Oreal offset the carbon footprint of its US operations, including from its largest facility in Florence, Kentucky. Appalachian Power, a Kentucky utility, is now seeking to boost renewables’ share in its portfolio to 34 percent by 2031. The decision was largely driven by a series of meetings with some of its largest current and prospective customers, including Walmart, who underscored their need for access to clean energy. And Kentucky has given birth to a start-up, Virtual Peaker, a software firm that coordinates demand-side devices to save energy, avoid the need for new plants, and save utilities and customers money.

The future of advanced nuclear energy is also promising. In March 2017, Kentucky lifted the nuclear moratorium, which opens new avenues for zero-emissions energy. TerraPower and General Electric have expressed interest in nuclear for Paducah, a city in Western Kentucky. TerraPower’s sodium-cooled fast reactor does not need enriched uranium, and can instead run on depleted uranium left over from other nuclear plants. TerraPower hopes to use as fuel the vast stores of depleted uranium located in storage containers at a US Department of Energy uranium enrichment facility in Paducah which operated for fifty years until being decommissioned in 2013.

Along with advanced energy, particular attention must be directed toward the communities most affected by the transition. A bipartisan effort, Kentucky Appalachian Regional Development Grant Program (KARD), developed by Shaping Our Appalachia (SOAR), is currently funding job creation and retention programs for coal communities. As of 2016, KARD had awarded $1,500,000 to community organizations and nonprofits to create new training programs and STEM centers, largely in Eastern Kentucky universities. Collectively, these initiatives will yield an estimated 3,300 jobs for the region.

Expanding local development programs like KARD, embracing and meeting large corporations’ desire for greater clean energy options, and supporting innovative Kentucky energy start-ups and advanced energy demonstration projects together have the potential to transition poverty-stricken coal communities into centers of durable economic growth. The seeds of such a transition have been planted, but prudent policies and forward-looking leadership will be needed to see them grow.

David Livingston is deputy director for climate and advanced energy and Kayla Soren is an intern at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center. You can follow David on Twitter @DLatAC

Image: Aerial photo of First Point, Second Point and Four Poles, Black Mountain Off-Road Adventure Area. Photo by Brandon Goins.