Note: This blog is the second in a series examining the global energy transition through the lens of communities with a significant stake in the traditional energy economy. In examining the social, political, and economic dynamics, policy choices that are made or missed, and the approaches that seem most promising and scalable, there is the possibility of strengthening social cohesion and equitable outcomes amid the global energy transition.

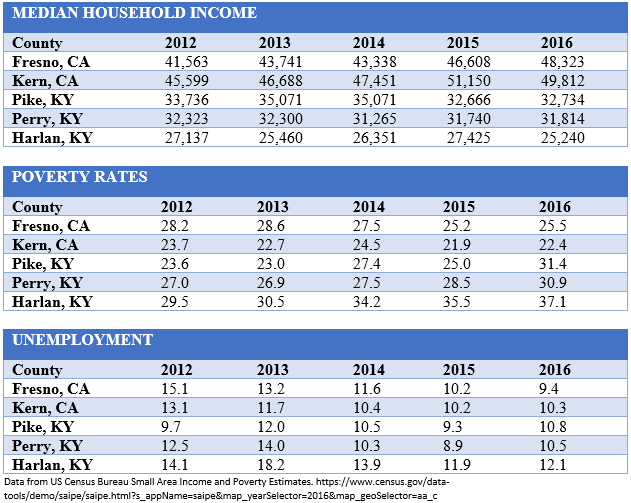

Despite assumptions that California is an affluent and prosperous state, a comprehensive assessment of various US congressional districts on metrics of health, education, and income in 2008 placed the San Joaquin area’s 20th congressional district as the worst performer in the United States. In 2010, the San Joaquin Valley earned the moniker “Appalachia of the West.” Indeed, the broader Central Valley of California is home to three of the five US regions with the highest percentage of residents living below the poverty line. Agriculture and oil, the two main economic building blocks of the San Joaquin region, are both exposed to commodity price volatility and have failed to deliver a modern, diversified regional economy.

In 2013, Kern county, the most oil dependent in the Valley, made up 70 percent of California’s oil production and 10 percent of US production. As oil production elsewhere in the United States increased as a result of the shale revolution, oil production in Kern has fallen by over 22 percent. The petroleum industry dropped from providing 50,000 jobs and comprising 25 percent of Kern’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2015 to 40,000 jobs and 20 percent GDP in 2017.

Yet, in recent years, the Valley has displayed unusual economic resilience (particularly since 2012) and growth. The trends are starker when compared against the performance of regions in Kentucky covered by the first post in this series. While recently rising oil and agricultural prices have played a role, this is also due to economic diversification, including the region becoming increasingly attractive for renewables investment.

Notably, a suite of state-level policies and accompanying revenue redistribution mechanisms have been critical components of the region’s new economic drivers. Two statewide policies have been central to the San Joaquin Valley’s economic turnaround: cap-and-trade and renewable portfolio standards.

In 2012, California adopted cap-and-trade in a 51-28 vote, with San Joaquin representatives in the minority. Despite this opposition, there is increasingly strong evidence of the net economic benefits of cap-and-trade. In practice, the cap-and-trade system imposes costs on carbon polluters, who must invest in emissions reductions and/or purchase credits in order to comply with their respective emissions “caps.” The auctioning of credits generates revenues for the state, which are then recycled back into the state economy via a “Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund” (GGRF). In the San Joaquin Valley, for instance, these GGRF funds are being spent on the local portions of a statewide high-speed rail project, along with other sustainable development projects.

In line with a statutory requirement to spend GGRF funds with a particular focus on disadvantaged communities, the San Joaquin Valley has received, and will likely continue to receive, a disproportionately high share of GGRF spending in comparison to imposed compliance costs. Between 2013 and 2015, for example, cap-and-trade policies had a net positive impact on San Joaquin of $202 million, added approximately 1,600 jobs, and created $4.7 million in new (non-climate-related) tax revenues.

One notable use of GGRF revenue includes $70 million for a West Fresno Satellite Campus of Fresno City College, featuring programs in renewable energy and low carbon transportation, among others. This has tripled investment in economic development for Fresno. And the city is in good company for receiving GGRF revenue that furthers local development. In nearby Porterville, $9.5 million from cap-and-trade revenue has brought an additional ten zero-emission battery-electric buses and infrastructure to disadvantaged communities. In Los Angeles County, $35 million was granted to Watts for economic development projects including public housing, solar panel installations, and an electric car-sharing program. While it is too early in the lifecycle of most of these projects to appraise their total economic impact, they nonetheless represent a source of investment in growth sectors and technologies.

The second key policy has been the Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS). In 2002, California approved an RPS that required utilities to deliver 20 percent of their retail electricity from renewable energy sources by 2017. The policy was continuously amended to include more ambitious targets, and utilities are now required to meet a 50 percent renewable energy requirement by 2030. Since the adoption of RPS, California’s electricity rates have experienced minimal upward movement compared to installed renewable generation capacity, which has tripled. Construction of renewable energy infrastructure has created at least 88,000 jobs in San Joaquin, 90 percent of which were created between 2012 and 2015.

Kern has become a national renewable energy leader, with large-scale corporate investment playing a key role. In 2014, Google invested $145 million to a solar plant outside Bakersville. In 2015, the MidAmerican Energy Holding Company installed one of the largest solar plants in the world, “Solar Star,” between Kern and Los Angeles County, which can power roughly 255,000 homes and is creating over $500 million in regional economic impact in addition to 650 construction jobs. Kern is also is home to the largest single wind farm in the United States, the “Alta Wind Energy Center” at Tehachapi Pass, and is now the top producer of wind energy in California, with more than two-thirds of its current wind generation capacity having been installed since 2010.

Renewables investment is also harnessed for broader benefits. The Renewable Energy Neighborhood Enhancement Wind Business Investment Zone (“RENEWBIZ”) grant program, for example, is funded through incremental revenue associated with property taxes from wind farms in East Kern and distributes small matching grants to private businesses and nonprofits in unincorporated communities to upgrade and enhance infrastructure and public spaces. By 2014, the solar and wind sector alone produced $30 billion of private investment and over 1,600 permanent jobs in Kern County.

New policies implemented in San Joaquin counties have also sought to increase renewable energy access. In 2015, the county adapted its zoning ordinance to make it easier for building owners to install on-site energy systems and streamlined the requirements for energy storage projects. The HERO program uses property assessed clean energy financing (PACE) to finance 100 percent of solar and other energy efficient technology on resident or commercial properties. Property owners repay PACE through property taxes over the course of up to twenty years. Between July and December 2017, PACE financed nearly $346 million in home improvements across 14,350 projects in California. These installations are expected to save customers $420 million on their utility bills over the expected useful lifetime of the products installed, create an estimated 3,116 jobs, and generate more than $533 million in economic impact across the state. However, two cities in Kern County have ended PACE, as the program is largely based on home equity, with income not being a factor. Since Kern County is predominantly low income, it is particularly crucial to ensure that advanced energy policies are not regressive if they are to achieve broad support and afford broad benefits.

The following two trends connected to the unique character of the region are also worth highlighting.

In some cases, renewable energy is not so much challenging the area’s oil heritage as complementing it. GlassPoint solar has developed a process by which concentrated solar power is used to generate steam that, in turn, is utilized for enhanced oil recovery in Kern County’s depleted oil wells. The company is partnering with a separate solar firm to build, by 2020, what will become one of California’s single largest solar projects at the Belridge oil field in the San Joaquin basin.

In addition, the area also benefits from a long history of constructive industry-military cooperation on renewable energy issues, including the Coso geothermal project, in operation since the late 1980s on site at the Naval Air Weapons Station at China Lake, California. The project received a $4.5 million grant from the Department of Energy in 2002 to apply hydraulic fracturing technologies (such as those used in shale oil and gas drilling) for increasing the productivity of the geothermal site.

Of course, San Joaquin Valley’s economic turnaround cannot only be attributed to climate policies and renewable energy growth. Nevertheless, the positive benefits of a smart, sustainable transition to an advanced energy economy are clear.

David Livingston is deputy director for climate and advanced energy and Kayla Soren is an intern at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center. You can follow David on Twitter @DLatAC

Image: Fresno, California (Photo by Grant Porter on Unsplash).