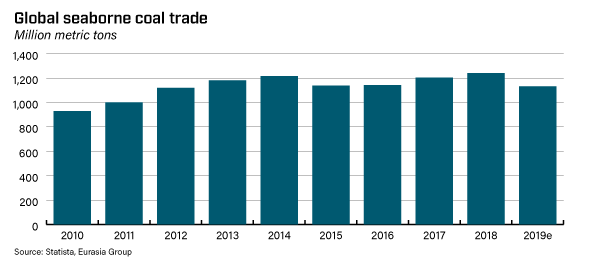

Coal has been the main fuel of industrialization over the past century and a half. To this day, it remains a key feedstock for power generation (thermal coal) and in making steel (coking coal). Yet demand for coal appears to be peaking, with seaborne coal trade volumes plateauing at just over 1.2 billion tonnes.

While coking coal remains indispensable for steel, thermal coal is seeing competition from cleaner fuels. Carbon Brief published a study this month showing that worldwide electricity generated from coal dropped by 3 percent, or 300 terawatt hours, this year. While shipping data still showed a slight increase in trade, it seems clear growth has topped out.

Peak demand in America & Europe

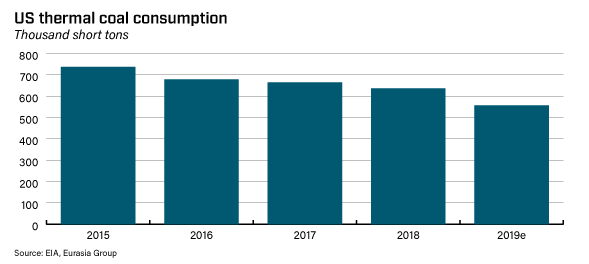

Global coal use may be peaking, but there are big regional differences. In the United States, thermal coal has been steadily pushed out by cheap shale gas and renewables. As a result, thermal coal consumption has been declining for half a decade.

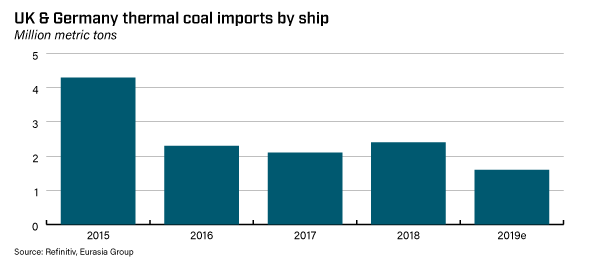

In Europe, coal also looks like it is in terminal decline. Shipped imports into former coal powerhouses Britain and Germany have collapsed over the past five years amid rising renewable and natural gas capacity while electricity consumption peaked in the early 2000s in both Britain and Germany, and has steadily declined since. Germany still burns a fair bit of domestic lignite to generate electricity, but Britain today uses barely any coal for power generation.

Asian coal use still strong

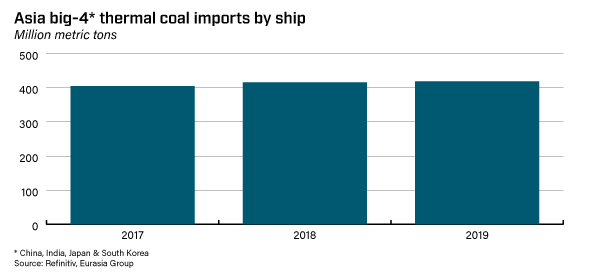

Asia is different. Shipped thermal coal imports by the top four consumers—China, Japan, India and South Korea—have remained strong at record levels above 400 million metric tons. While consumption is falling in traditional import powerhouses Japan and South Korea for the same reasons as it is in Europe, consumption is still rising in key emerging economies like China and India. While both have pledged to combat pollution and climate change, they still rely heavily on coal-fired power. In both countries, coal also receives political support as authorities fear a move away from coal would trigger rising unemployment from mining closures.

Many emerging economies across Asia—including Indonesia, Vietnam, and India—also so far prefer domestic coal to imported liquefied natural gas (LNG), as governments resist spending big to develop LNG’s costly infrastructure, which will only raise the country’s import bill.

Still, with consumption declining in Japan and South Korea but growing in China and India, Asia’s thermal coal demand is creeping up. Considering North America and Europe’s decline, it is likely the world has reached peak thermal coal demand.

So what (for oil)?

Peak coal demand has not gone unnoticed. Also fearing a peak in demand and potentially stranded assets, oil producers are putting off spending on future output. Meanwhile, investors are cutting exposure to petroleum assets to comply with sustainability targets and shareholder pressure.

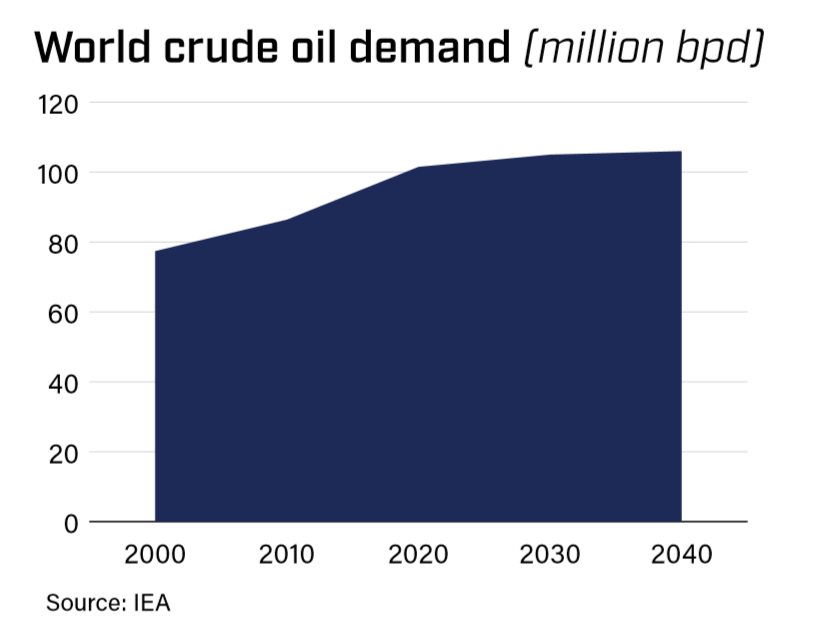

Yet peak oil demand has yet to happen. Consumption this year rose by 1 percent and will for the first time average above 100 million barrels per day. While growth is slowing, consumption will likely increase for years to come.

When it eventually peaks, a look at coal gives a glimpse of what could happen in other sectors. Peak demand does not mean consumption will fall off a cliff—coal demand has so far plateaued at or near records, with pockets of growth still around.

Serving those pockets will remain a profitable business for miners that produce the sought-after coal. The most modern coal-fired power stations—euphemistically named “ultra-supercritical” and mostly under construction in Asia—use different coal than the ageing coal-slingers. This will favor different coal exporters. For instance, high quality thermal coal from Australia is better suited to meet demand from new power stations than coal from Indonesia, which tends to be of lower quality.

And while many European and American banks now shun coal, credit remains available as investors, including from Japan, where most “ultra-supercritical” turbines are made, still lend to projects they perceive as relatively clean.

Similar trends may be emerging in oil. Many investors prefer small and short-cycle oil assets like US shale or projects in fully developed markets like Europe’s North Sea to risky, costly and long-cycle new production like Brazil’s deepwater fields.

Like coal, the oil industry will see a shift in demand for certain crude grades even as overall consumption growth stalls, plateaus, or peaks. In shipping, this is already happening as a sulfur cap from January 2020 in marine fuels has pushed up demand for niche crude grades that are medium and sweet in quality. Tightening environmental regulation will soon hit gasoline and diesel consumption from cars, albeit at high levels. However, demand for oil from other sectors like petrochemicals (e.g., household chemicals, textiles, and consumer goods) will still grow for years. This will trigger another change in demand away from heavy/sour grades commonly used for transportation to lighter/sweeter types used more by the chemical industry. For specialized producers and investors, such an outlook offers opportunity even amid a peak in overall consumption.

Henning Gloystein is director, global energy & natural resources at the Eurasia Group. You can follow him on Twitter @hgloystein

Subscribe to the Global Energy Center newsletter

Sign up to receive our weekly DirectCurrent newsletter to stay up to date on the program’s work.

Image: Photo by Unsplash/Bence Balla-Schottner