The German electorate has dealt Angela Merkel a wake-up call. Her new term will define her legacy.

The German electorate has dealt Angela Merkel a wake-up call. Her new term will define her legacy.

Germany’s election was supposed to be a sedate affair. Merkel would be confirmed as chancellor. The German people—happy with brisk growth, 4 percent unemployment, and a high trade surplus—were supposed to rubberstamp their satisfaction with the status quo. Chancellor Merkel’s moment of peril in 2015—when her open-door policy brought more than 900 thousand asylum seekers to Germany—had passed.

A different campaign

But in an election that brought 75.6 percent of eligible voters to the polls, the German electorate dealt Merkel a wake-up call. The message was muddled. But certain trend lines—and warnings—are present.

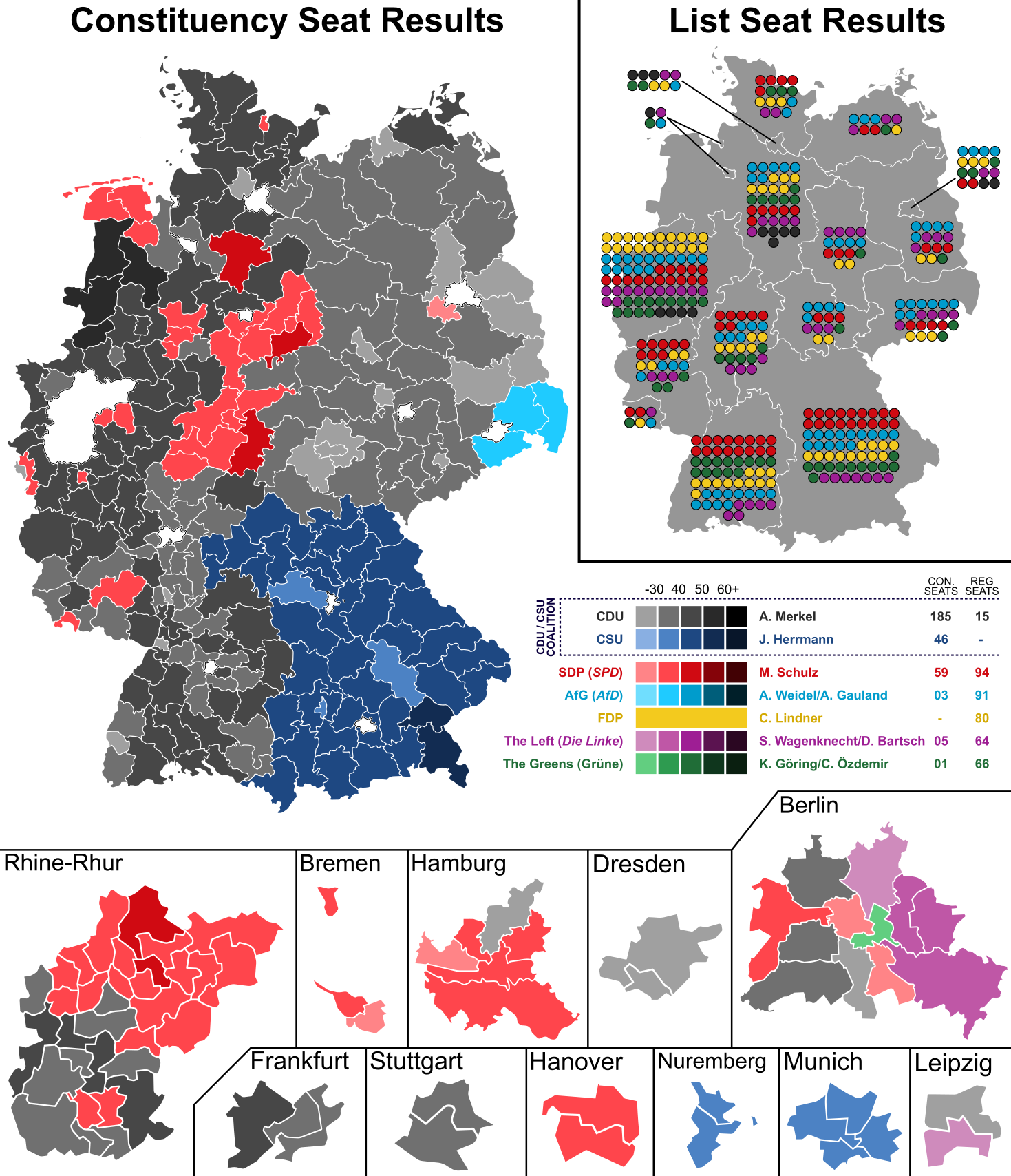

First, Germany is entering a period of uncertainty. Germany is not immune to the anti-establishment, reactionary forces sweeping the Western world. The comfortable position that the grand coalition had after 2013 has winnowed down to a mere 54 percent. The rightwing, populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) catapulted to the third strongest party in parliament. They even came in first in the state of Saxony. Combined with the Communist successor party—Die Linke—extremist parties will make up 22 percent of the new parliament.

Second, the German political landscape is more fragmented. Not one but two parties—the AfD and the pro-business, Thatcherite Liberals—that were not in the previous parliament are in. The size of the Bundestag will also grow from 631 to 708 seats. The center-left Social Democrats have already indicated that Merkel is on her own to forge a new governing coalition. That leaves Merkel no other option than an unstable coalition with the Liberals and ecologically-minded Green party. Most estimate that labored coalition talks could extend into early 2018.

Third, Germany has turned toward a more insular brand of conservatism. In total, 56.4 percent of Germans voted for parties to the right. That compared to 37.8 percent for progressive parties. But what drove this process? Economic performance, at least in the top line numbers, is not responsible for the rising tide of reactionary populism in Germany. Even 73 percent of AfD voters would describe the economic situation in the country as good.

Behind the swing

German voters bristled at attempts—both at home and internationally—to talk more about German leadership. As one former Defense Minister quipped wryly, “when Americans or Europeans talk about German ‘leadership,’ they really mean money.” It’s a resentment that many Germans feel. Some of the campaign’s best applause lines excoriated what others expected from Germans. Do more to support Macron’s EU vision with a transfer union to stabilize weak eurozone economies; do more on domestic spending to balance out Germany’s massive trade surplus; do more on defense spending to meet NATO’s 2 percent mark; do more sanctions against Russia and Iran; more on Brexit; and the list goes on.

And across the spectrum, there was a new-found embrace of the politics of national identity coupled with fear and distrust of Islam in political, social, and moral life. Even as the refugee crisis waned, the 2017 summer of Erdogan drew new anxieties into high relief. Germans in Turkey jailed for no reason. Reporters suppressed. Rule of law rolled back in the wake of a shadowy coup. Erdogan’s Islam-laced demagogic rhetoric attacking Germany for not allowing him to hold rallies on German soil. And all the while, over 60 percent of Turks from Cologne to Berlin to Hamburg voted in support of Erdogan’s authoritarian referendum. The incident left many German asking whether Germany’s Turks—and Muslims—share their values.

The EU factor

Many expect her next four years to be defined by the European Union. But it’s hard to see how she will forge an EU with cleaner lines with a smaller majority in the Bundestag, the austerity-driven Liberals in her coalition and a Euro-hostile AfD breathing down her neck. Given the domestic constraints, it won’t be easy.

Tyson Barker is Program Director and Fellow at the Aspen Institute Germany. He is a former US State Department official. Previously, Barker was the rapporteur for the Atlantic Council’s Transatlantic Digital Task Force. Follow him @tysonbarker.

This article originally appeared on The Hindu, and you can find the original here.

Image: Photo credit: Tobias Koch, Wikimedia Commons