The September 14 attacks on Saudi Arabia’s oil infrastructure will reverberate far beyond the Middle East as the economic and political consequences become more apparent. As the world’s largest oil consumer and importer, China is especially vulnerable to disruptions to energy markets, and how it responds to this could have important ramifications for the Middle East.

So far Beijing’s response has been characteristically low-key. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying condemned the attack and called for the “relevant parties to avoid taking actions that bring about an escalation in regional tensions.” The use of “relevant parties” is telling; China has thus far declined to blame anyone for the attack, saying they will wait for conclusive facts.

Despite the measured response, leaders in Beijing have to be concerned. The Middle East is an important pillar of China’s energy security and an important hub for its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Stability in the region and the Persian Gulf in particular is of economic and strategic interest. China’s approach to the Middle East has been to engage with every state, regardless of regional rivalries, developing strategic partnership relationships based on shared interests. While this leads to the impression that China is claiming neutrality in a fraught regional security landscape, Beijing does play favorites, and its preference is to work with states that share its vision of stability.

Having that been said, the energy aspect is important. In the wake of US sanctions on Iran, Beijing has leaned heavily on Saudi Arabia to meet oil demand. Between August 2018 and July 2019, Chinese imports from the Kingdom nearly doubled, from 921,811 to 1.8 million barrels per day, accounting for 16 percent of Chinese total oil imports. To be so reliant upon a state with demonstrated security risks has to be troubling. That prices jumped so substantially is another concern. With Brent crude futures spiking by nearly 20 percent after the attacks, China is paying a reported $97 million more per day.

Beyond energy the possibility of conflict in the Persian Gulf creates a lot of problems for Beijing. While the exact number of Chinese expatriates in the region is unknown, there are hundreds of thousands. Dubai alone has a Chinese community of over 300,000. There are billions of dollars worth of Chinese assets in the Gulf, with more than $123 billion worth of Chinese foreign direct investment flowing into the Middle East since the BRI was rolled out in 2013. It is the largest external source of foreign direct investment in the Middle East, and one would expect that it wants to see those investments secure.

All that is to say that if indeed it is proven that the Iranian government is responsible for the attack, expect to see Beijing’s relations with Tehran cool down significantly. The two states have long had strong relations and signed a comprehensive strategic partnership in 2016. This is the highest level in China’s hierarchy of partnerships, reserved for states that are perceived to play an important international role, politically or economically. This comes with a commitment of the “full pursuit of cooperation and development on regional and international affairs.” At the same time, it is a very asymmetrical relationship: Iran needs China much, much more than China needs Iran.

Beijing is Tehran’s top source of imports and top export market. In contrast, Iran represents China’s thirty-third largest export market, between Chile and Nigeria, and ranks twenty-fourth for imports. Iran is also less useful in terms of the BRI, which is essentially a project about international connectivity. While Iran is geo-strategically located, it is isolated within its own region and internationally, meaning it has less to offer China than Saudi Arabia and its Middle Eastern partners and allies. It’s worth pointing out as well that China also has a comprehensive strategic partnership with the Saudis, signed the same week as the one with Iran, and that Saudi Arabia and its Gulf Cooperation Council partners are deeply engaged with China in the BRI. If Iranian aggression threatens China’s interests in the Middle East, it would certainly test the durability of their partnership.

Another important consideration is the trade war. Like everyone else, Beijing has taken advantage of the US security umbrella in the Persian Gulf to build a bigger economic and diplomatic presence in the region. US preponderance provided a low-cost entry; security was guaranteed. With trade becoming weaponized, however, Beijing has to be rethinking its minimalist security role in the Middle East. The importance of the region to China’s energy security, BRI-related infrastructure investment, and deepening commercial relations all add up to make the Middle East highly important. Relying on the United States to provide security and maintain open shipping lanes creates a very dangerous vulnerability.

The attack on Saudi Arabia could be another factor that leads to a more robust approach to China protecting its Middle East interests. This in turn could add a dangerous element to China-US competition.

Jonathan Fulton is assistant professor of political science at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Follow him on Twitter: @jonathandfulton.

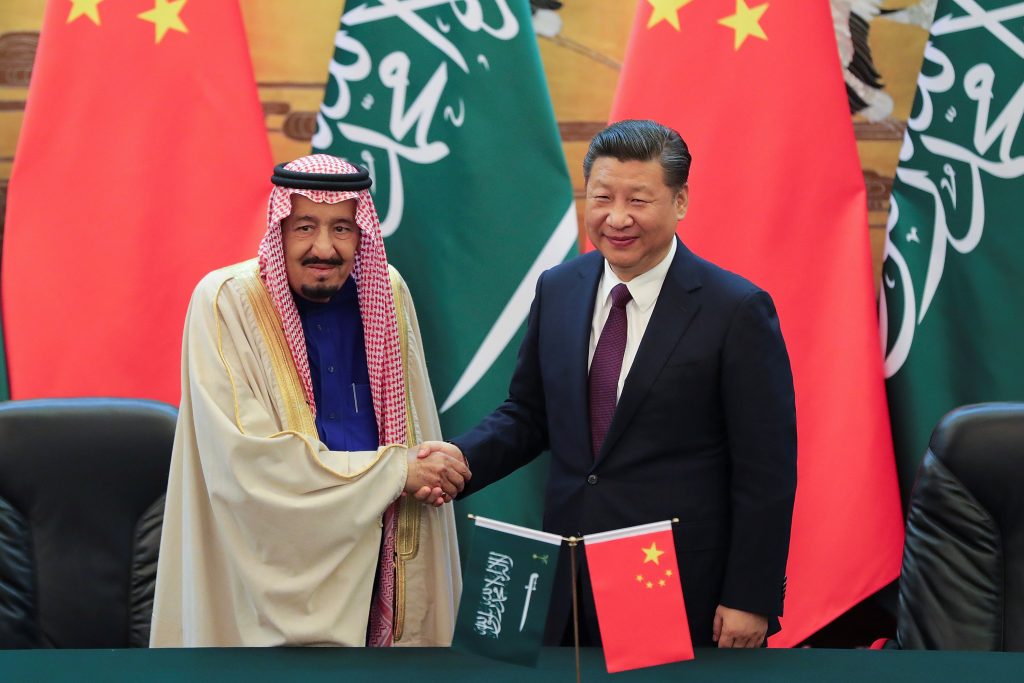

Image: China's President Xi Jinping and Saudi Arabia's King Salman during a signing ceremony in Beijing, China on March 16, 2017. (Reuters)