Prompted by the United States’ unilateral withdrawal from the nuclear deal with Iran (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action or JCPOA), the remaining signatories are urgently seeking ways to maintain the agreement—both for strategic reasons and to preserve its trade benefits. A British, French, and German proposal to launch an independent channel for maintaining trade with Tehran, however, is unlikely to succeed and risks undermining the effectiveness of European economic sanctions.

Prompted by the United States’ unilateral withdrawal from the nuclear deal with Iran (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action or JCPOA), the remaining signatories are urgently seeking ways to maintain the agreement—both for strategic reasons and to preserve its trade benefits. A British, French, and German proposal to launch an independent channel for maintaining trade with Tehran, however, is unlikely to succeed and risks undermining the effectiveness of European economic sanctions.

The three European countries (also known as the E3) are reportedly pursuing the establishment of a special purpose vehicle (SPV) to evade US sanctions and ostensibly maintain legitimate trade with Iran. The proposed SPV would essentially act as an accounting firm, tracking credits against imports and exports without the involvement of European commercial or central banks. For example, Iran could ship crude oil to a French firm, accumulating credit that could then be used to pay an Italian manufacturer for goods shipped the other way —without any funds traversing through Iranian hands. By using credits instead of cash, the SPV would not require any funds to transfer outside of the European Union (EU). Supporters of the proposal contend the SPV would keep such funds safe from the reach of US sanctions.

While the E3 may see merit in preserving the JCPOA through an SPV, such a mechanism is directly counter to broader EU policy interests in ensuring the effectiveness of UN and EU economic sanctions. Creating a shell mechanism to potentially skirt US sanctions is shortsighted for two reasons. First, the SPV is unlikely to prove a viable alternative to the global financial system nor an effective means of shielding European firms from US sanctions as the US government would likely consider these to be prohibited transactions rendering the SPV irrelevant. Second, the SPV directly undermines the EU’s ability to enforce the more than thirty sanctions programs it currently has in place, as well as future sanctions programs.

The looming November “snapback” of US sanctions on Iran, particularly on its economic lifeline—the oil sector—is the primary driver of the EU’s motivation for identifying an alternate payment mechanism. EU leaders likely fear that Iran will continue to comply with the nuclear deal only if it can still export oil. Once the significant US sanctions snap back into place following their multiyear suspension under the JCPOA, any global firm engaging in proscribed business with Iran may be subject to sanctions by the US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC).

The EU has already taken steps to try to mitigate the impact of US President Donald J. Trump’s May 2018 decision to withdraw from the JCPOA. In August, the EU amended its 1996 Blocking Statute, which purports to protect EU firms “against the effects of extra-territorial application of legislation adopted by a third country, and any actions based thereon or resulting therefrom.” The statute enables European firms to seek compensation for damages arising from US sanctions and also allows for potential penalties against European companies that comply with US sanctions without the European Commission’s approval. The Blocking Statute’s original intent was to mitigate the impact of US sanctions on Cuba, Iran, and Libya. Following a 1998 agreement between the United States and the EU, the need for the statute was largely mitigated, and the statute has essentially been dormant since then.

Read the rest on the New Atlanticist blog.

Samantha Sultoon is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global Business and Economics Program and the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

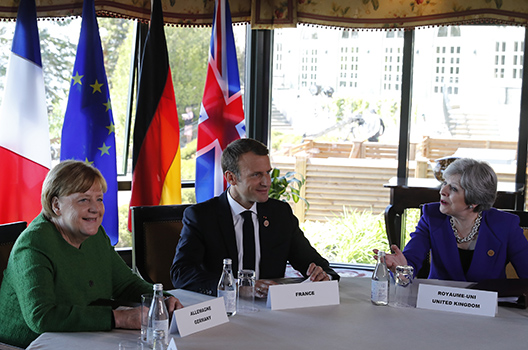

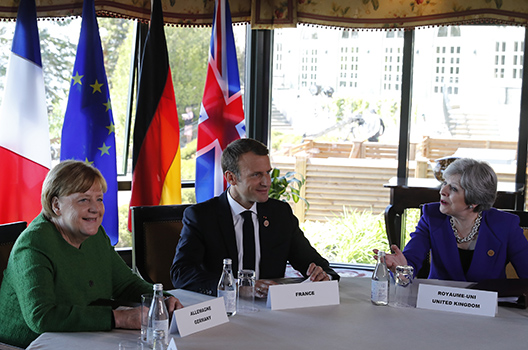

Image: German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron look on as British Prime Minister Theresa May (R) speaks during their meeting at the G7 Summit in the Charlevoix city of La Malbaie, Quebec, Canada, June 8, 2018. (REUTERS/Yves Herman)