Hemmati: The dark horse of the Iranian presidential election?

A technocrat is running for the presidency as Iran’s economic challenges stack up. One wonders if the former Central Bank of Iran (CBI) governor Abdolnaser Hemmati, a moderate, stands a chance. His performance in the debates and his wife’s appearance in an interview have certainly garnered attention in what is expected to be a historically-low turnout election on June 18.

Hemmati’s candidacy was a surprise to many until he appeared at the interior ministry to register on May 15. He had previously denied any political ambitions, but his background demonstrates an ambitious man climbing the ladders of the clerical establishment.

Photos from the early days of the revolution show a smiling, young Hemmati next to the founder of the Islamic Republic Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and former President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani. During the eight-year Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, he oversaw war propaganda in the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting and became the news department head in 1989. Later, he served as the vice president for political affairs under Rafsanjani’s brother, Mohammad Hashemi Rafsanjani, from 1989 to 1994. He still is a member of Kargozaran Sazandegi, a party founded by technocrats close to Rafsanjani in the 1990s. A graduate of Tehran University, Hemmati became one of many officials who received their graduate degrees while working full time. He received his master’s in economics in 1987 and his doctorate, also in economics, in 1993 from Tehran University.

Hemmati would later become the head of Central Insurance from 1994 to 2006, followed by the chief executive officer of Sina Bank from 2006 to 2013, and, finally, the head of Melli Bank from 2013 to 2018. Then, in June 2018, Hemmati became Iran’s ambassador to China, only to be summoned urgently to take the reins of the CBI a month later.

Just weeks before, in May 2018, US President Donald Trump had withdrawn from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, closing international business channels with Iran. In response, Rouhani vowed that Iran would not bend to pressure. He picked Hemmati to run the CBI partly because he was known to have international connections and ties with many financial institutions in Asia.

The re-imposition of punitive US sanctions revealed a depth of vulnerability in the Iranian economy. Years of sanctions and economic mismanagement had encouraged corruption and many Iranian banks were approaching insolvency. The banking sector challenges increased significantly when hardliners refused to accept banking regulations mandated by the global anti-terrorism financing watchdog, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). In addition, the Iranian rial began a period of free fall, registering new low records daily, as Iran’s oil revenues began to drop. The new CBI governor was expected to address multiple unfolding crises.

Hemmati proved a shrewd banker, promoting a market approach while staying loyal to the regime’s official political line, publicly claiming sanctions did not affect Iran’s economy. His first task was to stabilize the currency exchange market. It is still baffling why the Rouhani administration decided to fix the official exchange rate at 42,000 rials, locking its reserves in a government-controlled distribution system. The decision prevented the CBI from creating a unified currency exchange market. Before the spring of 2019, Iran had four different exchange rates with micro-markets in various cities and across the border in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Still, Hemmati managed to find new sources for foreign currency, as the domestic demand for it became insatiable. He used Iran’s Integrated Exchange System as a marketplace where Iranian exporters could sell their foreign currency revenues. However, Iranian exporters found CBI’s initial high-handed approach discouraging and refused to sell their hard-earned foreign currency at pre-set rates. As a result, from April 2018 to March 2019, they brought home only $8 billion from total earned revenue of $40 billion. Exporters only became cooperative after the CBI accepted a rate close to the free market exchange rate and prosecuted some exporters.

Hemmati used the same tactics in dealing with insolvent military banks. Avoiding publicizing the problem and strictly following the official line, he merged five banks—all affiliated with the security apparatus—with Iran’s oldest bank, Bank Sepah. Their balance sheets included many toxic assets, which they could not liquidate in markets. As their liabilities surpassed their assets, thousands of deposit owners became concerned that their savings might be lost. Merging the banks on the edge of solvency with a substantial bank was the obvious economic solution. Since the government and military organizations were the principal shareholders, the merger neither required nor meant information sharing. No one discussed or questioned why the military banks had gone belly up in less than a decade. Thus, the political cost to the ruling establishment was kept at a minimum.

There is little doubt that Hemmati is a member of the political establishment of the Islamic Republic, close to centrist and moderate conservatives of the old days. However, he is one of the few previously young revolutionaries who have learned some lessons from their experience. He does not confront the opposition within the political establishment but asks for a seat at the table.

Hemmati’s approach to implementing FATF regulations is a case in point. Iranian banks needed FATF to fight off their increasing isolation. In February 2020, FATF placed Iran on its blacklist for failing to comply with internationally accepted anti-terrorism norms. Instead of rallying against hardliners, Hemmati demanded that the CBI be included in the elaborations on FATF and Combating Financial Terrorism policies. However, when the Expediency Council, an advisory body that manages disputes between the Guardian Council and parliament, failed to approve FATF regulations, he publicly claimed that rejecting FATF had no impact on Iran’s economy.

Since the campaign season began, Hemmati’s performance in the three debates has attracted some attention. In polls conducted by moderate and reformist media outlets, Hemmati is ahead of Judiciary Chief Ebrahim Raisi, the hardliner favorite and expected winner of the election. However, according to Tejarat News, a few hours after the first debate, Raisi became the number one candidate again. One outlet blamed this change on cyber-attacks and polling manipulation. Before the change in numbers, Hemmati was ahead of other candidates with 55.4 percent of the vote.

Hemmati isn’t the only one garnering attention. His wife, Sepideh Shabestari, conducted a state television interview on his behalf in early June. Interestingly, she appeared not in chador, which the wives of previous presidents traditionally wear, but a headscarf. Shabestari’s spotlight appearance became the discussion of Persian language social media.

On June 9, Hemmati took things a step further by saying that he’d potentially be willing to meet with US President Joe Biden if he was elected. “America needs to send better and stronger signals,” he added.

Today, candidate Hemmati claims that he would have ratified FATF standards in a heartbeat if it had been up to him alone. Many political elites and financial community members in Iran consider Hemmati’s handling of military banks and FATF as reasons he should be the next president. They believe Hemmati can address Iran’s economic challenges with a mix of behind-closed-doors politicking and market-based policies, thus, minimizing the political cost to the regime. As a result, some reformists are warming up to the idea of a potential President Hemmati.

However, Iranians are exhausted of years of corruption, sanctions, and economic volatility and have grown apathetic to the elections. It might be too much of reformists to ask them to vote for a savvy banker, let alone any candidate in the June 18 vote.

Ali Dadpay is an associate professor of finance at the Gupta College of Business at the University of Dallas in Texas. Follow him on Twitter: @adadpay.

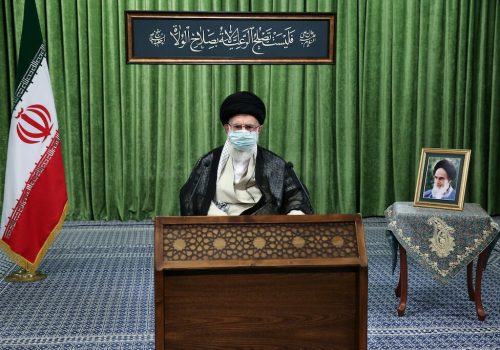

Image: Meeting of the Iranian presidential election 2021 candidate, Abdolnaser Hemmati with his supporters in the presence of journalists and media in Tehran, Iran. (Photo by Sobhan Farajvan / Pacific Press/Sipa USA)