Forty years have passed since the Iranian Revolution—a revolution that promised to usher in democracy, freedom, and prosperity for all. Ayatollah Mohammad Yazdi, an influential cleric, recently exclaimed that Iran has progressed more in the last “forty years than it had in the 400 years prior.” Has it?

This note offers some perspectives on selected economic and social indicators, and compares Iran’s performance to that of three comparator countries of similar developmental starting points and approximate population sizes in the 1950s. The selected countries include Turkey because of historic and cultural affinities; South Korea because in the 1970s Iran and Korea both strived to become industrial powers; and, Vietnam because, like Iran, its developmental trajectory was overshadowed by a long conflict with the United States and extended periods of economic embargo. Additionally, these countries’ geostrategic location placed them at or near the frontlines of the Cold War and ultimately shaped their internal and external outlook. The review goes back to 1950 because of the availability of consistent cross-country data that would make it possible to observe the trends before and since 1979 in order to assess if Iran has been able to overtake, underperform, or keep pace with its comparators since the revolution.

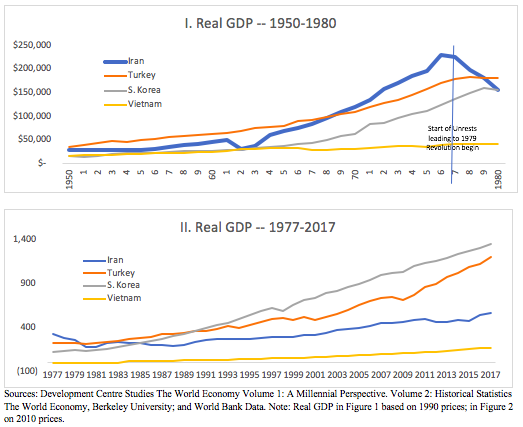

GDP Trends

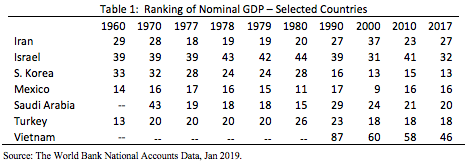

In 1950, Turkey’s gross domestic product (GDP) was 22 percent higher than Iran’s, but the GDP of Korea and Vietnam were less than 60 percent of Iran’s. In 1977, the last “normal” year before the revolution—1978 saw the start of unrest and strikes that ultimately brought down the monarchy—Iran’s economy was 26 percent larger than Turkey’s; 65 percent higher than Korea’s, and nearly 5.5 times the size of Vietnam’s. In 2017, Turkey’s nominal GDP was 2.4 and Korea’s 7.2 times larger than Iran’s, while Vietnam is 70 percent of Iran’s and is being touted as an emerging Asian Tiger. For a country that has one of the world’s most abundant natural resources, data suggest that the Iranian economy did not maintain its pre-revolutionary trend and could not keep pace with its comparators.

Using GDP ranking as another metric of economic importance, in 1960, Iran was the world’s 29th largest economy. Turkey ranked 13th and South Korea ranked 33nd. By 1977, Iran had climbed to 18th place, Turkey was 20th, and Korea 28th. In 2017, Iran was 27th, Turkey hovered around 18th, and Korea had by now become the 13th largest economy in the world. Vietnam, too, has had a phenomenal rise from 87th rank to 46th place—a jump of nearly 40 ranks in less than thirty years. Oil producers such as Mexico and Saudi Arabia rank today among the top twenty economies, a group which Iran could have easily been part of given its vast oil and gas endowments. Still, Iran remains the second largest economy in the Middle East and North Africa. It is still considerably larger than Egypt, Norway, South Africa, or Israel, to name a few.

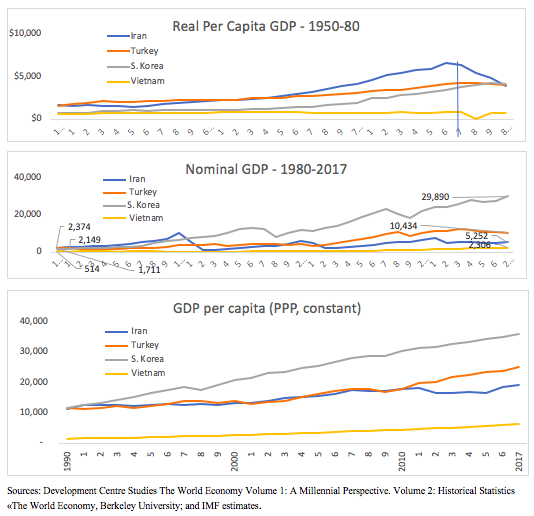

Per Capita Income

Mirroring GDP trends, Iran’s per capita income has also grown far slower since the revolution. In real terms, the three decades before the revolution saw Iran’s per capita income jump by a factor of 3.2 times; in the four decades since the revolution, it has only doubled. In 1980, Iran’s nominal GDP per capita was higher than its comparators (In 1980: Iran= $2,374; Turkey = $2,169; Korea = $1,711; and Vietnam = $514; In 2018: Iran = $4,838; Turkey = $11,125; Korea = $32,774; and Vietnam = $2,482). In 2017, Turkey and Korea had reached a multiple and Vietnam over half of Iran’s. In terms of purchasing power parity, Korea outpaced the comparators significantly. Iran kept pace with Turkey but fell behind after 2000.

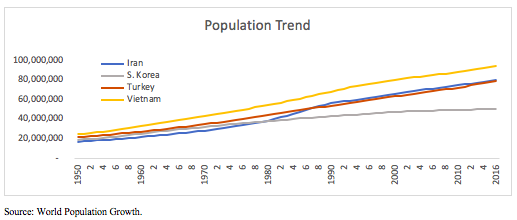

Beyond the slower growth, Iran’s rapid and Korea’s low population growth rates are additional factors behind the vastly different GDP per capita outcomes. In 1980, Iran and Korea had roughly the same population (Iran = 39.5 million; Korea = 38.1 million). Today, Iran has 30 million more mouths to feed (Iran = 81 and Korea = 51 million).

Income Distribution and Poverty Rates

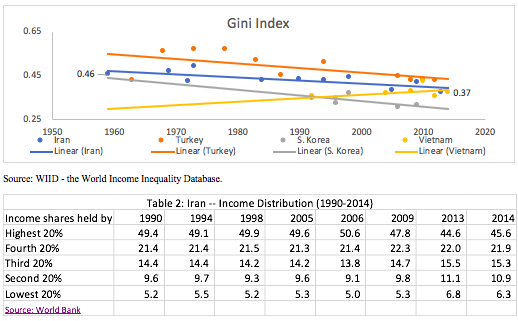

The slow GDP and GDP per capita growth has led to widespread perception among the Iranian public that poverty is pervasive and that income inequality has worsened considerably. In fact, Iran’s income inequality, as measured by the Gini index, shows a slow downward trend and has improved in comparison to pre-revolutionary Iran. The Figure below shows that the trend has been downward, and that Iran’s income distribution has improved, in similar direction as Turkey and Korea, though Vietnam’s has deteriorated. As can be seen in Table 2, the upper income quintile still controls close to half the nation’s wealth, but its share has gradually declined slightly since 1990 benefiting minor gains in the lower three quintiles.

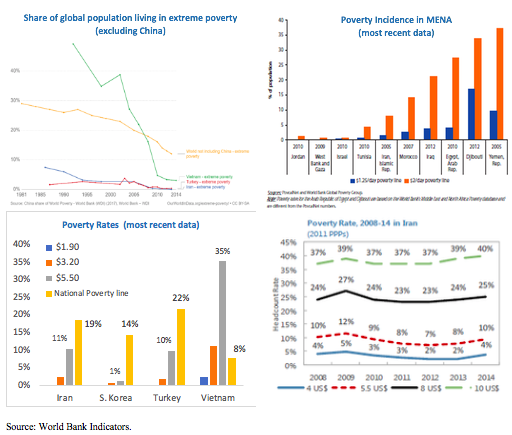

Future generations will mark the twentieth century as the period when global absolute poverty, as measured by the two international poverty markers of $1.25 and $2.00 per person per day, dropped precitpitously. Using this measure, absolute poverty in Iran has also declined sharply. Its rates are among the lowest in the Middle East and North Africa region and the world. However, international poverty benchmarks may not be meaningful measure for most countries, and national poverty lines are more widely used indicators. On this basis, one in every five Iranians lives below the national poverty line and nearly 40 percent are considered to be near poverty as measured by $10 per day per person. This suggests a large share of the population’s high vulnerabilityto slip into poverty or remain chronically poor. The feminization of poverty is also a worrisome trend, with women accounting for about two-thirds of the poor. Therefore, while absolute poverty has been largely eradicated, relative poverty continues to be a real problem and has not been overcome in the past forty years since the revolution.

Compared with the three selected peers, as a way to illustrate the possible economic growth path Iran could have taken, it has underperformed. The revolution’s promise of prosperity has not been realized, though Iran has made some progress on alleviating absolute poverty. According to available data, income inequality has declined. But the perception of high and worsening inequality persist, which fuels public discontent.

Missed Opportunities

The lackluster growth has many reasons, some of which are due to internal policies, and others due to external factors. Among internal policies, two topics stand out.

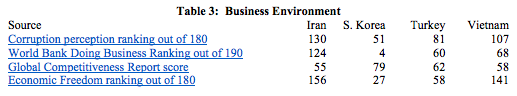

The first is that massive post-revolutionary nationalization and expropriations essentially removed Iran’s emerging entrepreneurial and industrial class that had risen in the 1960 – 1970s. Contrary to some belief that they benefited from the shah’s crony capitalism, most early industrialists came from humble beginnings and were self-made businessmen. Among the many examples are the Khayyami brothers of Mashhad, who rose from middle-class origins to start Iran’s car industry, which is today Iran’s third leading employer (after oil and gas), and still places Iran as the world’s 16th largest car producer. Nearly all industrialists emigrated and built successful businesses abroad while grooming their next generation into leaders in cutting-edge global corporations. To grow a robust private sector necessitates an industrial class—such as the Kocs and Sabancis of Turkey or Chung Se Yungs of Korea. The expropriated companies were handed over to be managed by trusted and ideological insiders. In its forty years, the Islamic Republic has not been able to foment a genuine and independent entrepreneurial class. Cronyism combined with corruption, vested interest, policy unpredictablity, and a cumbersome business environment stymie would-be entrepreneurs. As Table 3 demonstrates, Iran ranks low—and below its comparators—in most cross-country ratings.

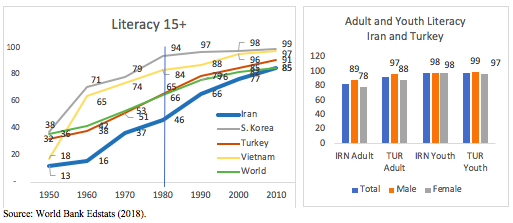

The second missed opportuny is Iran’s waste of its human capital. In 1950, Iran’s adult (15+) literacy rate was 13 percent and below world averages and those of its comparator peers (see below). At low literacy levels, the first hurdle is the dearth of schooled people who could be trained as educators to teach others. Thus, the progress is slow. Considerable effort was made to raise literacy to about 40 percent before the revolution. Since 1980, Iran has caught up with the world average of about 85 percent, though still below Turkey, Korea, and Vietnam. This increase was mainly due to educating the young generation and eliminating the gender gap between boys and girls. For this group, literacy is nearly universal and at par with global best performers. The cohort of older Iranians, mostly in rural areas, who remain illiterate, push Iran’s average literacy rates down (see below).

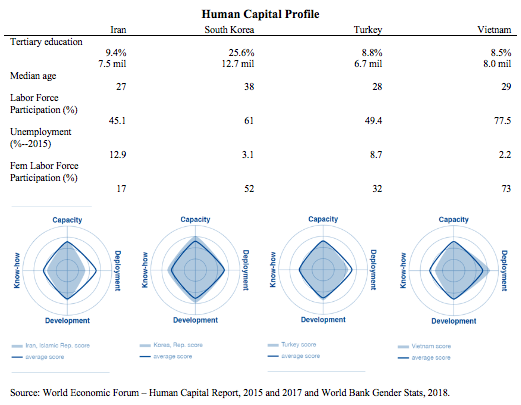

Literacy rates alone may not provide the full picture of a country’s human capital endowment. The post-1980 rise in literacy led to considerable investments in tertiary education. Nearly one in every ten Iranians has at least one univesity degree. According to the 2015 World Economic Forum’s Human Capital Report,Iran had close to to a million more university graduates than, for instance Italy, about three-quarters of a million more than Turkey, and 3.5 times as many as Israel, a prominent global talent pool.

With a low median age of 27 and its large educated youth, Iran has had a unique demographic window to provide it with a high growth opportunity. But this potential is vastly underutilized. Iran has the lowest overall labor force participation rates, only 45 percent of the work force are economically active, and one of the highest unemployment rates, particularly so among the educated youth. This is well illustrated on the ‘deployment’ axis of the figures below.

A deciding factor in the low overall participation rate is women. At 17 percent female labor force participation rate, Iran is among the lowest in the world, despite the fact that women constitute over 60 percent of the university graduates and over 70 percent of students in STEM fields. If women were economically active “under similar assumptions [as elsewhere], [the IMF] estimates the GDP boost in Iran would be around 40 percent.”The low labor force participation is due to a myriad of gender-discriminatory laws and regulations.

Markets

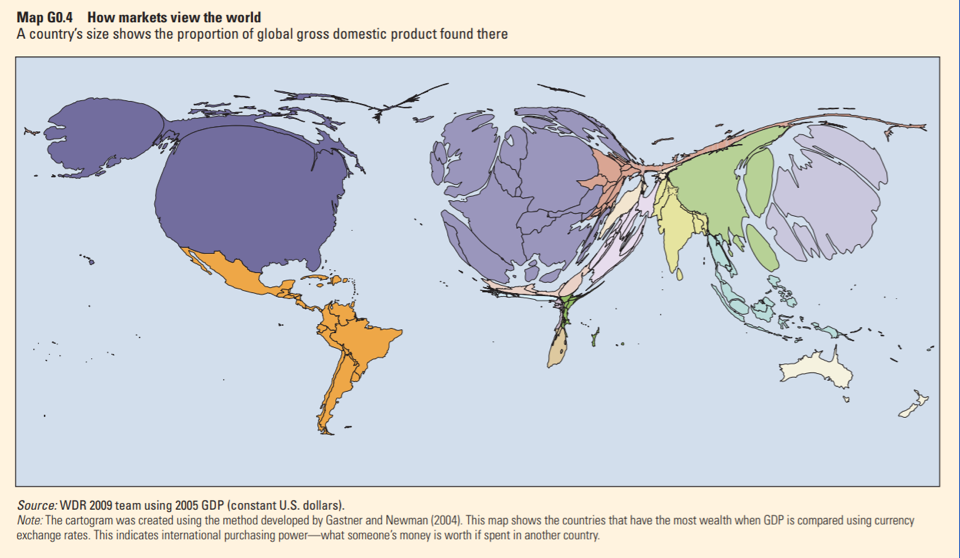

Countries do well when they can benefit from proximity to, and dense, economic activity. The Figure below presents the world on the basis of size of markets. A major underpinning of the rise and growth of the three comparator countries, presented in this note, has been their ability to capitalize on growth in surrounding countries and use these as jumping boards to reach broader global markets.

Iran is literally at the connecting point between the two large balloons representing the Asian and European markets, while central to Russia and Africa. Therefore, it could have benefited from its unique economic geography and scale up its industry. While some degree of economic and regional integration has taken place in the last decade, there are many instances where Iran has been left out or missed important opportunities. Geopolitical pressures, mostly the adversarial relations between the US and Iran, have undermined opportunities. They may have also resulted in Iran being bypassed in several multi-country infrastructure projects, such as the ambitious TAPI pipeline project that links India to Europe, the Central Asian gateway that is to run through Pakistan, or the South Caucasus Pipeline that runs from Azerbaijan through Turkey to Europe. Capitalizing on markets at its door step might have propelled Iran to become the Japan or Korea of West Asia and remain within the top twenty economies in the world.

Conclusion

Domestic policies to promote entrepreneurship could have helped Iran to capitalize on Iran’s young and educated population. And, a foreign policy geared to regional and global integration could have permitted Iran to benefit much more from its unique economic geography. Hence, while it has certainly made progress in the last forty years, it has failed to keep pace with countries which trailed Iran prior to the revolution. In many ways, the story of Iran reminds one of the old fable of the tortoise and the hare. While the Iranian economic hare was able to hop ahead for a short period of time, it has been the steady one-foot-in-front-of-the-other strategy that has advanced its comparators. Iran still has the fundamentals to regain its prominance—an opportunty that should not be missed.

Nadereh Chamlou is an international development advisor and former senior advisor to the Chief Economist of the Middle East and North Africa Regionat of the World Bank, where she spent more than three decades in technical, coordination, managerial, and advisory positions. Follow her on Twitter: @nchamlou.

Image: Iranians shopping at a local bazaar (Tejarat News)