Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe will finally make a trip to Iran on June 12. Since becoming prime minister at the end of 2012, every time Abe attempted to visit Tehran, the idea was eventually withdrawn mainly due to US disapproval, according to rumors.

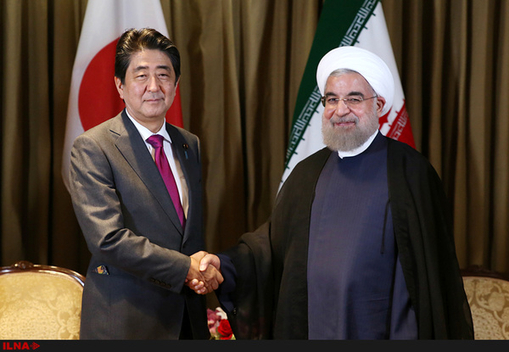

However, Prime Minister Abe has met Iranian President Hassan Rouhani seven times already, not only in New York on the sideline of the UN General Assembly every year since 2013, but also at the sixtieth annual Asia-Africa Conference in Indonesia during 2015. The Tehran visit will be the eighth meeting between Abe and Rouhani. It will be the first visit by a Japanese prime minister since 1978. (However, it will be Abe’s second visit to Iran since he accompanied his father, then Foreign Minister Shintaro Abe, in 1983.)

How did this visit come about and what can Abe achieve? Rumor has it that it was actually US President Donald Trump who brought up the idea of “mediation” between the US and Iran in April, during Abe’s visit to Washington. The sudden visit by Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif to Japan in mid-May has been understood in this context, while the news of Abe’s Iran visit came to surface just after his meeting on May 24 with US National Security Advisor John Bolton in Tokyo, a day prior to a visit by Trump himself.

While in Japan on May 27, President Trump confirmed that he approved PM Abe visiting Tehran to facilitate a “talk” between Iran and the United States. According to a June 8 report by Sankei newspaper, Trump told his Japanese counterpart that he strongly encourages Abe to visit Iran since he is “the only person” who President Trump can entrust the role of mediation with Tehran.

Among the various opinions that have been presented regarding what to expect from Abe’s Iran visit, not many of them are optimistic. There is an enormous gap between US and Iranian perspectives on the current situation. Regarding the nuclear agreement known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), for example, while Iran continues to comply with it, Trump has prevented others from holding their end of the bargain by threatening to re-impose sanctions on countries trying to expand economic ties with Iran.

Due to US sanctions, most Japanese companies that sought business opportunities in Tehran after the implementation of JCPOA had to give up on the idea and withdraw. Tokyo even stopped importing oil from Iran, which Japan has constantly relied on for more than half a century, regardless of occasional difficulties in imports. Along with other countries that were prohibited by the US from importing Iranian oil, Japan stopped its Iranian oil imports on May 1.

Tokyo imported 130,000 bpd of oil from Iran in 2018, which is only 4.2 percent of all oil imports. It’s a much smaller amount compared to in 2003, when Japan imported close to 700,000 bpd from Iran—more than 15 percent. Considering the modest oil that Tokyo imported from Iran last year, some might think that Japan could actually do without it.

However, Iranian oil is important for Japan not because of the amount imported, but because of the need to diversify its energy sources. As a country that mostly relies on imports for energy, it’s expected that Abe will discuss Japan’s energy supply on his Iran trip.

Abe will also likely play a role in reducing the level of tension in the Persian Gulf region, whose stability is crucial for Japan’s energy security.

In order to contribute to Middle East stability, Abe will need to act as a trustworthy mediator. Without a doubt, he will need to make Japan’s own proposal rather than just convey President Trump’s message to the Iranian leadership. The proposal would have to be based on a good understanding of the concerns of each party that has played a role in exacerbating tensions in the region.

Abe has already spoken to Saudi, Emirati, and Israeli leadership during the past week as preparation for his Iran visit. The purpose was to make clear that Tokyo will not side completely with any country—including the US and Iran—while also understanding their concerns.

Confrontation without dialogue could easily lead to an escalation. Thus, one hopes that Abe finds a possible point of discussion between the US and Iran, after speaking with Iranian leadership. Although it’s hard to imagine a US-Iran direct dialogue—either on the sidelines of the G20 in Osaka at the end of this month or in New York on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in September—it’s worth a try. What Abe will try to demonstrate is Japan’s own way of easing tension in the Middle East.

It’s worth noting that Japan has its own Middle East policy independent from the United States’. Even after the US withdrawal from the JCPOA, Tokyo has continuously expressed support for the nuclear accord as a valuable international non-proliferation agreement. One of Japan’s proposals could then be related to saving the JCPOA, such as focusing on the Iranian need to normalize oil trade. Another area Japan might focus on is conveying existing concerns that are outside the scope of the JCPOA, in order to urge dialogue on those other issues. A sense of fear on both sides has to be dealt with equally, through attempts to deepen mutual understanding of the other side’s threat perception.

Although it’s still unclear what exactly Japan will propose in the coming visit, it goes without saying that just one visit can never solve everything at once. By taking into consideration the concerns of all parties, the Tehran visit will certainly be a valuable step in the right direction not only for Japanese-Iranian relations, but also towards peace and stability in the Persian Gulf region.

Sachi Sakanashi is a senior research fellow at the JIME Center, Institute of Energy Economics, Japan (IEEJ).

Image: Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani on the sidelines of the 2016 United Nations General Assembly (ILNA)