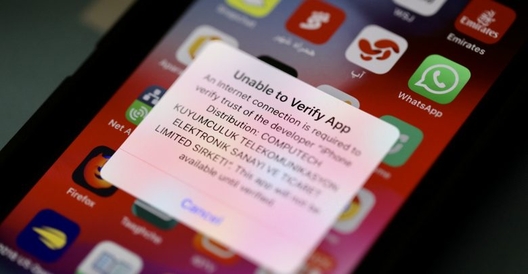

Soheila has a monthly routine. At the beginning of each month, she opens the Asan Pardakht app on her iPhone to make gas, phone, and water payments. But on this day, the bill paying application gives her the notification: “Unable to verify app.” Soheila is stuck with unpaid bills. Her only solution is to wait for the next morning to drive to her bank and make individual bank transfers for each of the bills—with a service charge she could have avoided through the app.This extra cost and additional errand to run seems like an implausible inconvenience in 2019, when she seemingly has access to all the devices and internet connections—including circumvention tools—that technology has to offer. Suddenly the expensive iPhone 6s Soheila’s son bought her from abroad two birthdays ago seems to have lost all its shine. The Apple notification and the Telegram messages Soheila receives from friends, who have discovered other inaccessible applications, are making it clear that Iranian applications are receiving the boot on iOS devices.

For Soheila, and many Iranians, these hurdles thrown into their daily lives have never been foreign. For decades she’s lived in a country going through different iterations of sanctions on her daily life, both figurative—from the Iranian government—and literal—from the US government. According to Apple, “Under the US sanctions regulations, the App Store cannot host, distribute or do business with apps or developers connected to certain US embargoed countries.”

Since 2017, when Apple started disconnecting Iranian applications, Iranian businesses hosting applications circumvented this ban through developer enterprise certificates: unofficial applications meant for testing, and not public use. They started using these certificates to freely host and share their applications with all Iranian users.

When Apple blocked Iranian applications at the end of February, they were not implementing sanctions, but merely blocking applications because of their own policies. They had done this before when Apple removed developer applications hosted by companies such as Facebook for their research applications. This event, however, underlined the cat and mouse game ordinarily played between Iranians and government censors, except now it’s between Iranians and American technology companies.

Apple’s previous restrictions included the March 2018 decision to completely block access to its App Store in Iran. While many Iranians with iPhones found virtual private networks (VPNs) to get around this block, moments such as the Internet disruptions that were felt in the aftermath of the Telegram ban in April 2018 resulted in momentary disconnections from many applications and VPNs. For iPhone users without working VPNs, they were prevented from downloading new circumvention tools, having been cut from the VPNs that enabled them access to the App Store.

Other access hurdles Iranians have been experiencing include Google’s decision to block their App Engine and the Google Cloud Platform. These Google restrictions have prevented many Iranian startups and developers from taking advantage of all the opportunities of a free and open Internet. Even more, during the December 2017 – January 2018 Iran protests, the Google App Engine block meant they had restricted access to platforms that were using “domain fronting,” or, in other words, using Google to reroute their platforms to avoid censorship. The encrypted messaging app, Signal—which used the App Engine to circumvent censorship applied by countries like Egypt, the UAE, and Oman—were blocked from use in Iran, which has also banned the app. Access to Signal was crucial especially during the country’s mass protests when Telegram, the most popular messaging app in Iran, was also blocked. In another practice to comply with the US export control regulations, Khan Academy and Coursera—two major online education platforms—restrained Iranians’ full access to their websites.

At the same time, Iran’s startup sector is a burgeoning industry, contributing around 100,000 jobs a year to the Iranian workforce. These are huge contributions to a fledgling economy that suffers from 27 percent unemployment among young Iranians and over 40 percent among university graduates. Despite this, Iranian developers face restrictions developing iOS applications, as well as access to key software development infrastructure, including GitLab, a central platform for global tech companies including NASA, Alibaba, and Boeing. Gitlab was blocked for Iranians in 2018 when it switched over to the Google Compute Engine—part of the Google Cloud Platform—to host its infrastructure, another impediment for technology access.

Iranians who live outside the country also bear the brunt of sanctions and tech companies’ overly restrictive practices. In a haphazard practice of compliance with US sanctions, Slack temporarily banned users who had connected to their accounts from Iranian IP addresses. Later Slack reversed its decision and apologized for the mistake after public backlash. To avoid the hassle and financial burden of applying for export licenses, tech companies in the US are often reluctant to hire Iranian graduate students for temporary and internship positions, an experience faced by one of the authors of this piece.

These chilling effects on the ability of ordinary Iranians to have full or equal access to the Internet and its opportunities can be seen as deriving from hurtful US policies. But it also derives from the discriminatory implementation of regulations by companies once one understands the workarounds technology companies have to make exceptions for the sake of access.

The US government has been aware of the chokehold sanctions can have on one of their core human rights principles of Internet freedom. In order to counteract this, since 2010—as a non-partisan decision—the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) within the Treasury Department has released several General Licenses which would allow for “the exportation of certain services and software incident to the exchange of personal communications over the Internet” to facilitate the “free flow of information” for Iranians.

For further clarification, in 2014, OFAC issued the General License D-1 which authorizes private companies to provide certain “personal communications” technologies for Iranians. Despite re-imposing sanctions against Iran by the Trump administration, in a press release issued in March 2018, the US Treasury Department ensured that General License D-1 would stay intact on the basis of “fostering Internet freedom and supporting the Iranian people.”

Despite these reassurances, the reality is that various companies are actively working to limit access to the Internet for Iranians.

When we catch up with Soheila about a month later, we ask how she’s getting along.

“The apps are backed up through different names or web versions by the companies. For the ones still working, companies have multiple back-ups created in case Apple takes one down.”

And so, these persistent inconveniences continue for Iranians. The addition of these companies’ restrictive policies compound the Iranian people’s everyday fight against their government’s Internet censorship, and debilitating US sanctions impacting their economy and livelihoods.

In Silicon Valley, companies like Apple promote their idealistic visions of diversity and inclusion through slogans such as, “The best way the world works is everybody in. Nobody out.” They hold on to these slogans while consciously keeping an entire population of a country outside of their platforms, despite regulatory assurances that can allow them to fulfill their visions of “inclusion.”

Mahsa Alimardani is a technology and human rights researcher, completing her doctorate at the University of Oxford’s Internet Institute and working with the freedom of expression organisation, ARTICLE19. Follow her on Twitter: @maasalan.

Roya Pakzad is a research associate and project leader in technology and human rights at Stanford’s Global Digital Policy Incubator and Stanford’s Iranian Studies Program. Follow her on Twitter: @RoyaPak.

Image: An Iranian iPhone app unable to be verified (itiran)