The next generation of Iranian women dare to imagine a future with freedom. This is what they want us to see.

In the videos coming out of Iran these days, rarely is there a face behind the camera. But, often, the voice of a citizen journalist can be heard. Proudly, they declare the date, time, and location of their clip, sometimes adding a bit of their own commentary on what’s unfolding.

Among the stream of horrors in recent weeks, one such voice was striking. It belonged to an older man whose voice is bursting with excitement and admiration: : “I am so very happy, to know that the future mothers and fathers of this country are boys and girls like these.” His words sum up a feeling that has captured the hearts and hopes of Iranians, both inside the country and abroad.

That there is frustration and resistance towards the Islamic Republic is neither new nor secret. Iran has seen waves of protests since Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini entered power in 1979 and established an Islamic Republic, a regime which has encountered opposition since its inception.

A legacy of resistance

From the start, post-revolutionary opposition in the 1980s was met with a campaign of mass arrests and executions. In 1999, students took to the streets for six days of demonstrations, resulting in thousands of arrests and many missing, injured, or killed. In 2009, post-election protests spiraled into the biggest demonstrations in thirty years—a Green movement with over three million participants that went on for six months. Again, protesters were violently repressed, with a reported 3,700 arrested and at least eighty killed (though the true number is thought to be much higher).

Among the deaths of 2009 was the killing of Neda Agha-Soltan, a young woman who was shot by a member of the Basij militia, and whose death—caught on video—became a symbol of the government’s brutality, further propelling the protests. The most recent eruption in this decades-old pattern came in 2019, which was prompted by a fuel hike and turned into an anti-government demonstration, with security forces arresting and killing thousands. This round also inspired a worrying novelty: an Internet blackout—the longest in the history of any country.

Throughout these four decades of recurring outcry, women in Iran continued to wage another protest: against mandatory hijab imposed on them by the regime. Often, it was a clear but quiet protest, performed simply by wearing their head covering loosely and letting some hair show.

At times, though, their resistance has also been loud. Starting on International Women’s Day on March 8, 1979, days after the compulsory hijab law was first announced, thousands of women took to the streets in Tehran—hair uncovered and protected by human chains of male supporters—in opposition to the law. From 2017 to 2019, a series of protesters dubbed, “The Girls of Enghelab [Revolution] Street” took off their headscarves and stood on electric boxes, waving them in prominent public places in defiance of a system determined to control their bodies through its laws and so-called morality police. These girls were violently arrested and put on trial, with Iran’s judiciary spokesman suggesting that they were on “synthetic drugs.” At least three, Saba Kordafshari, Yasaman Aryani, and her mother, Monireh Arabshahi, remain in prison.

Such a steady stream of state-sanctioned repression could have numbed Iranians who oppose their government and its laws, lending itself to a sense of inertia and quiet frustration. Until very recently, Iranians and Iran experts alike held the impression that this may be true. What has unfolded over has dispelled any idea that Iranians had been scared into submission. And it is precisely those who the regime has tried to stifle the most—young women—who have brought about this seismic change.

Opposition by many means

Sitting on the other side of the world, it is hard to grasp the scale of their opposition and of the government’s heavy-handed repression campaign. Records of both are hamstrung by limited, VPN-supported Internet access and a media blackout. Yet, in all the ways they can—videos, Instagram stories, text messages, and voice memos to family abroad—Iranians are asking the world to try. To begin to fathom what they are fighting for, particularly the women and girls who have tired of being treated as second-class citizens in their home. Here are just some snapshots of resistance in recent weeks:

- On September 29, the Internet was struck by an image that was as simple as it was extraordinary: two women, eating breakfast in public, with their hair uncovered. The next day, one of them, Donya Rad, was reportedly arrested and released after a week in detention.

- On September 30, social media was flooded with the image of a daughter with a shaved head as she stood at her mother’s grave. In her hand is the hair of her mother, Minoo Majidi, had defiantly cut off—an act which had her murdered. As she went to join the protests, she is reported to have said: “If I don’t go, then who will? I have lived my life, let them at least not kill our youth.”

- October 1 was a day of action—of strikes and sit-ins at home and demonstrations abroad. The following day, the government locked in the students of Tehran’s Sharif University of Technology—Iran’s top STEM school—while its security forces unleashed violence upon them. Its intended message was loud and clear: no one is safe, not even the country’s brightest minds.

Schoolgirls take the helm

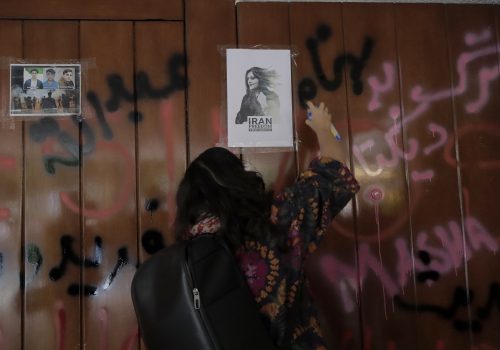

Yet, despite the crackdown, new forms of protest are being born every day. Since October 3, social media feeds have been showing how schoolgirls have taken the helm of the revolution. One video shows them, hair uncovered, expelling an Education Ministry official from their school while they shout “Bi-sharaf!” (someone with no dignity or ethics).

Furthermore, the portraits of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei that remain are now being used by girls in a new form of protest. Standing with their backs to the camera, their hair cascading down freely, they hold their hijabs with one hand and flip off the Supreme Leader with the other. The many variations on this theme make it clear that it’s not a one-off, but a trend spreading through classrooms and Persian-language social media. One viral video shows a class of girls who lay his portrait on the ground and take turns jumping on it; their jubilant giggles can be heard in the background and the video ends with their hands piled onto each other while they chant, “Don’t be scared, don’t be scared. We are all together.” Another video shows three elementary school-age girls marching together, waving their hijabs in hand and shouting, “women, life, liberty,” with the distinct fervor of young girls who need to be heard.

These girls are very aware of the weight of their gesture, giving the middle finger to the Islamic Republic’s system of chastity laws and morality policing, which have demanded total obedience from them and their mothers for over forty-three years now. Their courage, creativity, and endurance in the face of a regime set on “mercilessly confronting” them—not to mention the thousands of likes and millions of views cheering them on through Twitter and Instagram, with celebrities around the globe lending their support—speak volumes to the vigor and real power of their defiance. The government has responded by arresting these young girls and sending them for “psychiatric evaluation.” Despite the growing cost of their protest, they continue to stand with their hair down, middle fingers in the air, while burning portraits of the Supreme Leader.

As Iranians inside the country enter their fifth week of confronting the regime, the country’s four-million strong diaspora remains fixated on their struggle from afar via social media and phone calls and text messages on messaging apps. Fixated, both on their courage and seeming audacity, as they demand very un-audacious things: to own their own bodies; to live in a country where their mothers don’t feel compelled to risk their own lives out of hope their daughters may lead freer ones; to wear what they like to breakfast.

Rosa Rahimi is a graduate student at the University of Oxford.

Further reading

Wed, Sep 28, 2022

I’m a member of Gen Z from Tehran. World, please be the voice of the people of Iran.

IranSource By

To all the brave and beautiful people out there who know what freedom feels like, be our voice.

Fri, Sep 30, 2022

The protests in Iran have an anthem. It’s a love letter to Iran.

IranSource By

Shervin Hajipour's “For the sake of” has captivated the whole nation.

Mon, Sep 26, 2022

‘Women, life, liberty’: Iran’s future is female

IranSource By

Women, young and old, have been at the forefront of the uprising, just like every other protest in Iran over the past decades.

Image: Iranian people and their supporters are holding placards in memory of Mahsa Amini and against the Islamic Regime, during a demonstration called Revolution is Freedom organized in Amsterdam, on October 16th, 2022. (Photo by Romy Arroyo Fernandez/NurPhoto)