The dominant view in Washington since the 1979 Islamic revolution – with brief interruptions especially under the Clinton and Obama administrations – has been that Iran represents an irreconcilable challenge to US interests in the Middle East and must be countered with all tools of power, including sanctions and threats of war.

The dominant view in Washington since the 1979 Islamic revolution – with brief interruptions especially under the Clinton and Obama administrations – has been that Iran represents an irreconcilable challenge to US interests in the Middle East and must be countered with all tools of power, including sanctions and threats of war.

Influencing the debates over Iran’s nuclear program, regional influence, ballistic missile program and other Iranian policies are members of the US Congress and traditional US allies in Europe as well as regional powers such as Benjamin Netanyahu’s government in Israel and Mohammad bin Salman’s government in Saudi Arabia.

Lost amid the heated rhetoric of the debate is the impact US policy choices have on those who bear their brunt: the Iranian people. In this regard, President Donald Trump appears to have aligned himself with the most passionately interventionist and pro-regime change figures in the foreign policy establishment and to embrace Iranians only when he sees advantage to be gained in the wake of political turbulence in Iran. However, Trump’s unprecedented hostility towards Iran—exemplified in his efforts to undo the nuclear deal, maximize pressure and ban Iranians from the United States—stands to backfire by altering the Iranian public’s perception of the United States and sowing the seeds for perpetual US-Iran conflict.

Trump did not hold back in lauding the protests that swept parts of Iran in late December 2017 and early January 2018, tweeting that the Iranian people were “finally getting wise” and “finally acting against the brutal and corrupt Iranian regime.” He further declared that the Iranian people would “see great support from the United States at the appropriate time” as they “try to take back their corrupt government.” Such statements betray a belief that the United States can and should attempt to alter political outcomes in Iran and rest on the assumption that Iran is susceptible to such a coercive US strategy.

Nurturing Trump’s thinking on intervening in Iranian internal affairs have undoubtedly been past advisors such as Ezra Cohen-Watnick, previously the director for intelligence on the National Security Council, who reportedly pushed for using “American spies to help oust the Iranian government,” as well as virulently anti-Islamic Republic figures such as the new national security advisor, John Bolton.

The Washington-based advocacy group, the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), has also held Trump’s ear. Shortly after Trump’s inauguration, an FDD memo to the National Security Council called for examining “ways to foment popular unrest with the goal of establishing a ‘free and democratic’ Iran.” In the wake of the Iran protests, FDD CEO Mark Dubowitz wrote, “Americans of both parties should speak up. Iranians, like dissidents everywhere, are looking for support from abroad.”

However, Iranian society cannot be understood if reduced to a framework of a “totalitarian regime” against the “oppressed people.” Such Manichean simplicity obfuscates the multifaceted truths about Iranian society. To this end, it is telling that the protest wave in Iran died down within days of Trump’s exhortations.

This analyst was in Iran this past winter, staying with family, when the protests took place. It was immediately clear that many Iranians shared the grievances of the young, mostly rural protestors over rising living costs, limited economic opportunity and reactionary state policies that intrude on daily lives. The protests were triggered in large part by budget proposals to raise gasoline prices and cut cash subsidies. The demonstrations began in Mashhad—a bastion for conservative rivals of centrist President Hassan Rouhani. However, they quickly spread to other parts of the country and in some cases took on more radical anti-government slogans and became militant, with police cars and banks set ablaze and armed attacks on paramilitary installations and police stations.

Compared to the 2009 “Green Movement” demonstrations against Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s contested re-election, the winter protests drew far smaller crowds, albeit across a wider geographic area. Tehran, and Iran’s middle class more broadly, remained largely quiet. Even those with visceral aversion to the Islamic Republic were reluctant to join the protests. The chief reason was a fear of the consequences. Many looked worryingly at the vandalism and violence, and there was broad suspicion that the protests were being exploited; whether by outside powers or sinister internal forces. An overarching fear was that that Iran could become another Syria.

There was thus a palpable disconnect between the portrayal of the protests in major US media outlets and the reality on the ground. Iran is simply not as stagnant as it is often depicted. Despite restrictions, protests do happen, and Iran has an active political life and civil society. Political debate is also lively and open within the multiple ideological views accepted by the state. Domestic political quarrels have in recent years revolved around issues such as social welfare, ethnic and religious minority rights, and economic development and foreign policy. Parliamentary and presidential elections are consequently competitive and affect state policies.

Over the past decades, Iran has gone through immutable social-political change. Iranian society has become far more urbanized and digitally connected, and cultural norms have undergone rapid transformation in ways that often conflict with the traditional values espoused by the government.

As social, political, and economic grievances have mounted, some state bodies—especially the Rouhani administration—have attempted to channel popular anger to push for social-political-economic liberalization and increased institutional transparency. Indeed, the unanimous reaction of senior government officials to the protests, from Rouhani to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, was to acknowledge that people had legitimate grievances and a right to demonstrate. It was also made abundantly clear, however, that protests calling for the Islamic Republic’s overthrow and seeking to physically confront the state would be dealt with forcefully.

The winter protests also highlighted the deep divide between Iran’s internal reformist opposition and opposition groups abroad. Prominent and outspoken reformist dissidents such as Mostafa Tajzadeh, Abbas Abdi, Sadegh Zibakalam, and former President Mohammad Khatami—who still hold significant sway over Iran’s middle classes—sympathized with the protestors’ grievances but openly spoke out against destabilizing unrest. Meanwhile, Iran’s organized external opposition, ranging from the monarchist movement led by the Shah’s son Reza Pahlavi to the cultish Mujahedin-e Khalq (MEK), actively tried to push the demonstrations in a revolutionary direction.

Iran-based analyst Fareed Marjaee has said of the discord between Iran’s opposition movements: “The inside opposition aspires for measured steps and pace of change, so the situation does not lead to chaos … Most Iranians don’t want their everyday lives disrupted or the territorial integrity of their country challenged.” Marjaee adds: “The orientation of the outside opposition is based on theoretical observations from a distance. That’s because it doesn’t have to negotiate with the realities on the ground.”

It is imperative that Washington’s policymakers strive for an unbiased and holistic understanding of Iranian society. Trump’s determination to kill the Iran nuclear deal and his assembled “war cabinet” seem to signal that he wants regime change, by any means necessary. Dangerously, like in the lead up to the Iraq War, the “facts” on Iran are being fixed around the policy, not vice versa.

Trump and other Washington regime-change proponents were clearly emboldened by the protests this past winter and their rhetoric suggests a belief that they can incite Iranians to carry out another revolution. Implied in their narrative is that Iran is vulnerable and by bringing maximum pressure, the Islamic Republic will either collapse or make major unilateral concessions on its regional policies and ballistic missile program or agree to reopen the nuclear deal.

Iranians within the country have looked with fear at the serious role groups such as the MEK are playing with Trump advisors, chief among them Bolton, who proclaimed at a 2017 MEK rally: “The declared policy of the United States of America should be the overthrow of the mullah’s regime in Tehran. The behavior and the objectives of the regime are not going to change and therefore the only solution is to change the regime itself. And that’s why before 2019, we here will celebrate in Tehran.”

Another Trump advisor and close ally, former New York City Mayor Rudi Giuliani, has said of Bolton’s appointment in the White House: “If anything, John Bolton has become more determined that there needs to be regime change in Iran, that the nuclear agreement needs to be burned, and that you [the MEK] need to be in charge of that country.”

The Iranian people have long seen outside powers as attempting to influence and control their affairs, owing to the legacy of US, Russian and British interventions over the past two centuries. The majority of Iranians are consequently fiercely protective of their right to self-determination and determined to pursue a future based on their own views, wants, and struggles. Meanwhile, if Iran’s leaders have shown anything over the past decades, it is that they are canny pragmatists who prioritize regime survival. How they react to domestic pressures will determine their fate, and any US interference in this process will likely be counterproductive to the cause of positive change in Iran. Instead, it will likely spur a rally around the flag effect that will damage US-Iran relations for the foreseeable future.

Sina Toossi is a Senior Research Specialist at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, focusing on Iran and Middle East foreign-policy issues. He tweets @SinaToossi.

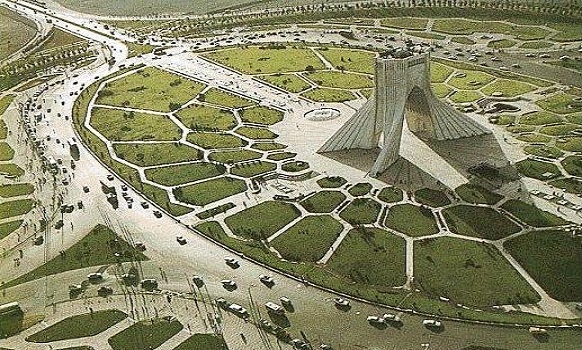

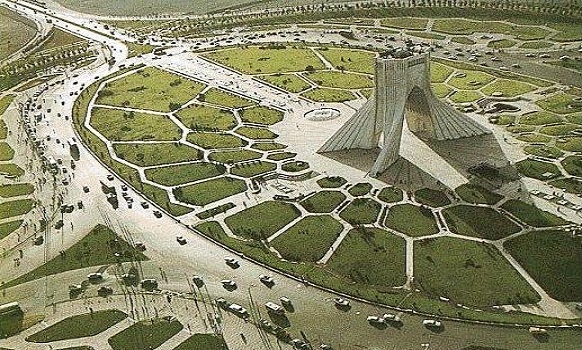

Image: Meydan-e Azadi - Azadi Square in Tehran (Wikimedia Commons)