25 years after Rabin’s assassination and Israel resembles its old self

This year marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the assassination of Israel’s fifth prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, who was gunned down in cold blood on November 4, 1995. Much has changed in the world since that fateful Saturday evening in Tel Aviv, but striking parallels might also be drawn—counter-intuitively, perhaps—between Israel’s circumstances around the time of Rabin’s death and the prevailing situation in the country today.

Then, as now, Israel was in a state of pronounced domestic turmoil, if for different reasons than those at present.

Discord over the Rabin government’s pursuit of the Oslo process with the Palestinians had bubbled over into the streets by late 1995. Opposition chief Benjamin Netanyahu blasted Rabin for poisoning public debate over the (de)merits of Israel’s bold peace moves. Netanyahu’s indignation was fueled ostensibly by disparaging taunts that a feisty Rabin hurled at his hawkish detractors, whom he accused of finding common cause with Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad militants, and said could “spin like propellers” for all he cared.

On October 6, eight days after the signing of the Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip—known widely as “Oslo 2″—in Washington, Israel’s Knesset ratified the deal by only the narrowest of margins. A 61-59 parliamentary majority was all that Rabin could muster to support the accord. The previous evening had played host to a fiery demonstration by the Israeli right in downtown Jerusalem’s Zion Square, where Rabin was denounced as a traitor and even depicted in the uniform of a Nazi SS officer.

The culmination of that clash in the abominable murder of Israel’s elected leader by a fellow Israeli Jew has not been repeated to date, but mutual recriminations between the country’s sitting prime minister and his antagonists are gushing over once again. Buckling under the combined weight of COVID-19 and his own personal troubles, Netanyahu has slammed his critics as “anarchists” and virus-spreaders. Anti-government protestors have, in turn, branded him as the “crime minister” and come out in thousands to demand his immediate resignation from office.

Following a rapid series of inconclusive elections, Prime Minister Netanyahu now stands atop a tenuous and dysfunctional coalition that appears destined for imminent collapse. The thread connecting his predicament with the turbulence of the Rabin era is an erosion of communal solidarity within Israeli society. Oslo’s momentum was largely derailed after Yigal Amir shot and killed Rabin twenty-five years ago; Rabin’s successor, then-Acting Prime Minister Shimon Peres, was defeated at the polls on May 29, 1996 and replaced by Netanyahu. What Netanyahu’s current jam portends for his more recent policy initiatives remains to be seen amidst a divided Israel that is becoming increasingly ungovernable.

In terms of its foreign relations, Israel under Rabin and Netanyahu has made significant inroads, expanding its global network of friends. The trajectory between their respective tenures was not at all linear, with periods during which Israel’s reputation was more toxic.

Rabin’s interactions with the Palestinians were a source of contention within Israel but were popular and celebrated outside its borders. His famous 1993 handshake with Palestine Liberation Organization chairman Yasser Arafat on the South Lawn of the White House unleashed a tide of support for Israel, paving the way for, among other things, the subsequent completion of a peace treaty between Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Rabin’s Jerusalem funeral, just over one year later, was attended by an extraordinary array of mourning royals, presidents, prime ministers, and other dignitaries—including the representatives of some Arab countries yet to extend formal recognition of Israel—offering a poignant sign of Israel’s respected status within the international community.

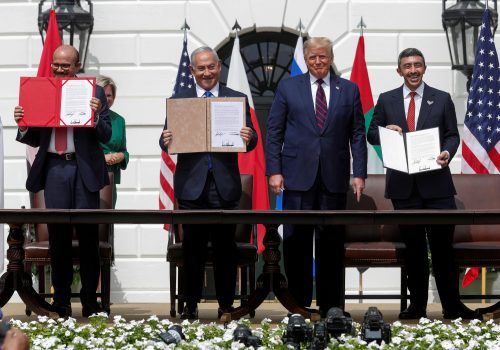

Fast-forward to the present day and Netanyahu, in close concert with US President Donald Trump, has shepherded Israel’s deeper integration into its home neighborhood with a string of normalization pacts of varying scope involving the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Sudan (Trump insists that more Arab nations will be joining in short order). These diplomatic breakthroughs come on the heels of Netanyahu’s earlier successes at upgrading Israel’s global profile, most notably in Asia and Africa.

Where Netanyahu’s path has diverged critically and obviously from the one taken by Rabin has been with regard to efforts at reaching a compromise with the Palestinians. The paradigm instituted by Netanyahu constitutes a reversal, in fact, of Rabin’s strategy to gain greater acceptance within the Muslim world through rapprochement with the Palestinian leadership. Enlarging the circle of Arab states prepared to contract peace with Israel will, according to Netanyahu’s own philosophy, clarify to Palestinian principals that “they no longer have a veto over peace and progress in our region” and, ultimately, “make peace between Israelis and Palestinians more likely.”

The next phase in Israel’s history will be impacted immensely by the choices of voters in the November 3 US presidential election. A second Trump administration would almost undoubtedly continue to support Netanyahu’s approach to dealing with the Palestinians, who may or may not try to mount a fresh campaign of violent resistance. It’s difficult to imagine how such a course of action would contribute to advancing Palestinian national aspirations.

A Joe Biden presidency would, by all accounts, be less tolerant of Netanyahu’s tactics and more attentive to Palestinian concerns. Dialogue between Israelis and Palestinians—the latter of whom broke off contact with the Trump White House in 2017—could conceivably resume. The sticking point might become the influence of progressive Democrats over US mediation of the conflict.

The decision of Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) to cancel her participation in a recent memorial for Yitzhak Rabin, an event organized by the ultra-dovish Americans for Peace Now, could be the harbinger of a new epoch in which even the most liberal elements of Israel are in fundamental disconnect with some members of the incoming ruling party in the United States. If there’s a Democratic win, it will fall to Biden to manage that tension in his ranks.

Shalom Lipner is a nonresident senior fellow for Middle East Programs at the Atlantic Council. From 1990 to 2016, he served seven consecutive premiers at the Prime Minister’s Office in Jerusalem. Follow him on Twitter @ShalomLipner.

Image: Daila Rabin, daugther of late Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, lights a candle, as part of what the Yitzhak Rabin Center say is the 25,000 candles lit during a memorial event commemorating the 25th anniversary of the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) crisis, in Tel Aviv, Israel October 29, 2020. REUTERS/Corinna Kern