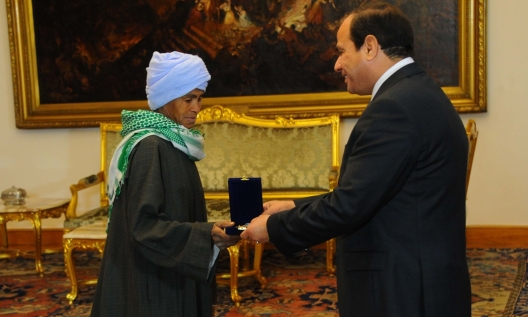

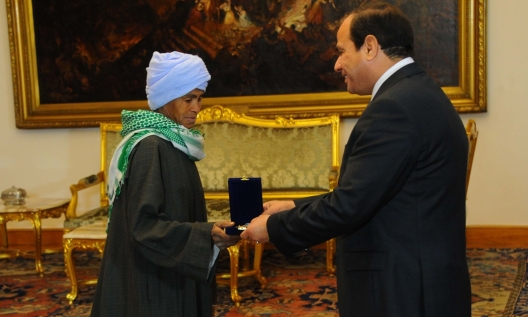

Last week, local authorities in Luxor honored an Egyptian woman for dressing as a man for four decades to support her family. Days later, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi presented Sisa Abu Daooh with an award for being an exemplary mother. There is no discounting the burden and pressures Abu Daooh faced and awarding her is a noble and good thing. But the real award would be to ensure that other women in her position do not have to go to the same lengths to find work, and to avoid sexual harassment.

Last week, local authorities in Luxor honored an Egyptian woman for dressing as a man for four decades to support her family. Days later, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi presented Sisa Abu Daooh with an award for being an exemplary mother. There is no discounting the burden and pressures Abu Daooh faced and awarding her is a noble and good thing. But the real award would be to ensure that other women in her position do not have to go to the same lengths to find work, and to avoid sexual harassment.

Abu Daooh’s story is a sad but uplifting one. At the age of twenty, her husband passed away, leaving behind a young pregnant woman. As a young mother with no education and no income, she shaved her head, dressed as a man, and set out to find work in a male-dominated world. Abu Daooh, or Um Hoda as she is known in her hometown, worked as a brick maker and a field hand until her health could no longer withstand the physical labor. She now works as a shoe shiner—a job culturally reserved for men in Egypt. For these sacrifices she has been described as an exemplary mother, and has been awarded 50,000 Egyptian pounds by the state.

Women in the Workplace

While receiving national recognition for overcoming her hardships and providing for her family is well-deserved, it also epitomizes how much has yet to be done for women’s equality in Egypt. Women make up roughly 50 percent of the population but represent only 23 percent of the workforce. In keeping with global trends, employers pay women less and are six times less likely to hire them for managerial positions. In rural areas, unpaid family workers make up almost 50 percent of the female labor force, compared with just over 6 percent in urban areas. Um Hoda, who hails from the more rural Upper Egypt, went to extreme measures to find herself on the other side of these figures.

Many of the cultural norms that stand in the way of Egyptian women’s success in the workforce are global, mostly wrapped up in fears related to raising a family. This is by no means a problem unique to Egypt, or even to the Middle East. Non-profits like the New Woman Foundation have taken a step in the right direction, organizing workshops in Upper Egypt to raise awareness on issues like wage equality and child care in the workplace.

Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment, whether in the street or in the workplace is also a phenomena not unique to Egypt, but one that is far more widespread. It is also an issue Um Hoda herself cited as one reason she chose to dress as a man—to avoid being sexually harassed in a male-dominated environment.

Egypt made significant strides last year when then interim-President Adly Mansour passed a sexual harassment law and, for the first time, Egyptian law addressed harassment in the workplace. While the law imposes a minimum jail term of six months and a fine of 3,000 Egyptian pounds, it is in the case of workplace harassment that punishment is at its harshest—two to five years in prison, and a fine ranging from 20,000 to 50,000 Egyptian pounds. However, at the time of its issuance, the law was seen as insufficient. According to women’s rights groups, the law’s narrow scope allows for forms of harassment that are all too common in Egypt. In the year since its ratification, it has only been applied in the event of rape.

Over the past four years, some cases of sexual assault even appeared to have been state sanctioned, used as a means to deter women from political participation. In other cases, the law itself justifies the harassment. The Supreme Constitutional Court even stipulated that a woman must dress chastely so as not to “lure men by her appearance and cause them to violate her, which would lead her to sin, and undermine her honor and status.”

Education

Um Hoda also stands as a reminder that Egypt’s women face inequality, not only in the workplace or socially, but also in education. Speaking about her choice to dress as a man, she said, “What else could I do? I can’t read or write, my family didn’t send me to school, so this was the only way.”

In 2012, Egypt’s overall illiteracy rate was 26 percent. For women, this figure jumps to 34 percent, compared to 18 percent for men. Social acceptance for female education in more rural areas, like Upper Egypt, is a responsibility the Egyptian government must take on.

Political Participation

Egyptian blogger Ahmed Awadallah describes Egypt’s rural women, who he says make up a quarter of the country’s population, as the “most disadvantaged group.” Many of these women are deprived of the opportunity to be a part of the political conversation that is primarily limited to urban areas. Last year, women’s organizations like Nazra were actively involved in the training and campaigning of female parliamentary candidates. Since then, a women’s quota has also been included in the parliamentary elections law.

While criticized by some, a quota serves the intended purpose of increasing female political participation and is an essential first step in a country like Egypt. These are small, key measures that must be taken to ensure that women’s voices are heard beyond the walls of their homes. But parliamentary elections, now on hold, are not likely to take place before the fall.

Even the state’s own National Council for Women has faced roadblocks when fighting for gender equality. In an attempt to overturn a court order that prevents women judges from sitting on the State Council, the judicial body responded by saying that NCW head Mervat Tallawy “lacked courtesy.” The State Council Judges’ Club also called for a lawsuit to be filed against Tallawy for interfering in judicial affairs.

Egypt’s constitution also does more harm than good by framing most of its references to women in the context of family and motherhood. “The state commits to the protection of women against all forms of violence, and ensures women empowerment to reconcile the duties of a woman toward her family and her work requirements,” Article 11 reads. In this way, the constitution drives home the fact that it is a woman’s responsibility, but not a man’s, to find a balance between her home life and work life.

Political wrangling aside, any steps made for gender equality in Egypt have been minimal. Instead, a woman dresses as a man in order to support her family—and is rewarded. There is something very wrong with this picture. As a state institution, the NCW, together with nonprofits who have worked for years on gender issues in Egypt, must be given the space to work. While it is easy to continue to say that now is not the time for women’s rights, these rights should be an integral part of any change brought on through reforms—whether in education, politics, or cultural spheres. Laws protecting women’s rights, such as the sexual harassment law, should be built upon and, more importantly, applied. This is the award that Um Hoda deserves.