In March 2011, just a few days after the uprisings began in Syria, the Secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, Saeed Jalili, made an unannounced visit to Damascus. He came with a clear message: Do not give in to the Arab Spring in Syria. Jalili met with President Bashar al-Assad and his top advisors to propose what he called a new “Iron Curtain” with Iran and Russia against a Western conspiracy in the region. Assad took the offer despite his father’s efforts to keep his dubious Iranian ally at arm’s length. Now the world watches as Iran increases its influence in both Syria and Lebanon, building toward an improved bargaining position with the West. By design, this process will soon render Bashar dispensable to all sides.

In March 2011, just a few days after the uprisings began in Syria, the Secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, Saeed Jalili, made an unannounced visit to Damascus. He came with a clear message: Do not give in to the Arab Spring in Syria. Jalili met with President Bashar al-Assad and his top advisors to propose what he called a new “Iron Curtain” with Iran and Russia against a Western conspiracy in the region. Assad took the offer despite his father’s efforts to keep his dubious Iranian ally at arm’s length. Now the world watches as Iran increases its influence in both Syria and Lebanon, building toward an improved bargaining position with the West. By design, this process will soon render Bashar dispensable to all sides.

As a diplomat for the Syrian Foreign Ministry in 2008, I attended a dinner during a diplomatic visit with Iranian Ambassador Ahmad al-Mousawi. He told me, “Iranians are all blooming flowers planted by Mohamad Nassif.” Nassif was a close advisor to Hafez al-Assad, and until recently the deputy vice president for security. Ambassador Mousawi’s statement hints at the complexities of Iran and Syria’s relationship over the last forty-five years. The Syrian constitution requires the president to be a Muslim. As an Alawite in the 1970s, Hafez al-Assad needed to put to rest any question of his religious legitimacy. He saw an opportunity in Musa al-Sadr, an influential Iranian Shia scholar in Lebanon. Assad supported Sadr’s rise, and in return, Sadr declared that all Alawites were brothers in the Shia Muslim faith. Sadr later suggested that Assad meet an influential Iranian Shia named Khomeini, then exiled in Iraq. Assad saw strategic benefit in supporting a future ally in the region, and supported Khomeini with intelligence, money, and assistance. Syria was the first Arab state to recognize the post-Shah government in Iran and backed it in conflicts throughout the 1980s, particularly that against Saddam Hussein in Iraq.

Lebanon proved to be the upper limit of the alliance between Iran and Syria. Iranian aspirations for regional dominance meant helping to establish Hezbollah in Lebanon to build influence there. Assad, however, created his own power players in Lebanon, culminating to a boiling point in 1986 for the first time in a Shia-on-Shia conflict. Hafez aligned his troops with the Amal Movement. Iranian Quds forces allied with Hezbollah. Hafez’s military victory in this conflict marked the Syrian-imposed limit of Iran’s expansionist policy in Lebanon. From then on, Hafez kept a distance from both Hezbollah and Iran, who were tireless their search for influence in the Levant. Hafez’s ailing health presented an opportunity to get closer to Syria’s power center through his son, Bashar.

It was an open secret among us in government that Bashar lacked confidence in his leadership abilities. Trained as an ophthalmologist in London and only groomed for leadership upon his brother’s death in 1994, many of us felt he was ill prepared to take the country’s helm. Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah developed a relationship with Bashar a few years before his father’s death in 2000 and endeared himself to Bashar in a way that his father would never allow. On the last day of national mourning for Hafez’s death, I went to Latakia with the foreign ministry to receive a brigade of Hezbollah fighters from Lebanon, who marched in a memorial parade. The display of military solidarity sent a message to Bashar—that Hezbollah would be a source of confidence.

The Iranian government had a harder time getting close to Bashar than their Hezbollah proxy. I attended several meetings with Iranian officials who sought to establish a “red phone” between Tehran and Damascus, so that Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei could coordinate with Bashar. Mohamad Nassif, knowing that Hafez would never have approved, rejected the idea before even notifying Bashar of the offer. In another attempt, Iran put key Syrian businessmen in control of shrines in Damascus and land for religious schools throughout Syria. Many of these businessmen had sold Iran weapons during its war with Iraq and helped acquire contracts with the Syrian government. Control over the shrines and schools ensured a steady flow of pro-Iranian influence and money in Syria’s capital to buy loyalty from elites. All the while, Iran still wanted control over Bashar.

The March 2011 uprising presented an irresistible opportunity for Iran to assert permanent dominance throughout greater Syria. Iran acted quickly, sending Secretary Jalili to Damascus just days after protesters took to the streets in Daraa. Jalili pitched the Iron Curtain plan to Bashar’s inner circle, assuring them that he knew the formula to neutralize protesters effectively. Iranian officials encouraged Assad to avoid concessions that could limit their influence over Assad’s inner circle. As the tensions evolved into armed conflict, Iran immediately sent advisors, snipers, and special forces to support Bashar. To compensate for defections from his officers, Bashar padded his loyalist camp with fighters and strategic planners from Iran and Hezbollah. Hafez spent decades protecting himself from such an incursion, but by late 2011, his son was desperate for a friend.

With Iran confirming a “no concessions” approach, Assad was wary of other states courting him with reform options. In 2011, we received separate reform proposals from Qatar and the UAE. Assad refused both. As the death toll escalated, Turkey seemed to dent the Iron Curtain with its proposal on January 27, 2012 to downgrade Assad to prime minister, but allow him to preserve his control over the military and air force intelligence. The plan proposed that Vice President Farouk al-Shara, a Sunni who had previously called for reconciliation, assume the presidency and place Assad’s brother-in-law, Assif Shwakat, as defense minister. The Iranians balked at the plan—they could not trust a reformer in the top position or Shwakat. Assad himself did not trust the Turks, but was willing to consider options as the conflict escalated out of control under the Iron Curtain. By February, Bashar engaged with the Turks on their plan in an effort to ease Western pressure.

In March 2012, Vice President Shara hosted reconciliation meetings with the opposition. Iran was furious and used its influence to stop any further meetings. Reconciliation posed a direct threat to Iran’s Iron Curtain strategy, threatening to reunify the country outside of the Iranian umbrella. On July 18, a bomb in Damascus killed Assif Shwakat and several other key members of the security apparatus. Iranian officials used the bombing to convince Assad that reconciliation would only bring more attacks on his inner circle. In response, Bashar became more intransigent, and avoided any restructuring that would reduce his power.

Meanwhile, Hezbollah proved to be an effective fighting force for Bashar. The Battle of Qusayr in 2013 marked an important moment in this relationship. Syrian forces tried to take the predominantly Sunni city—surrounded by Alawite areas—from the rebels three times and failed. Hezbollah entered the surrounding regions. Through media and propaganda campaigns, Hezbollah convinced the people that Assad could not protect them. When Hezbollah overtook the rebels in Qusayr, the surrounding Alawite communities were more adoptive of their propaganda and influence. Iran capitalized on this gain by establishing Syrian Hezbollah, investing heavily in the pro-government militias known as the National Defense Forces.

Through Hezbollah and the National Defense Force, Iran fostered an effective future insurgency in Syria. This core group of fighters, and the civilian populations they control, are Iran’s new stronghold for influence and trust in Syria. As Assad’s barrel bombs drove large portions of Syria’s Sunni and other populations out of the country, Hezbollah and the National Defense Force stoked sectarianism, convincing the Shia and Alawite populations that Bashar cannot protect them—only Iran can. This strategy has now placed Iran as the key power broker for Syria, regardless of Bashar al-Assad’s fate.

Iran’s incursion into Assad’s inner circle makes it capable of causing the collapse of his regime. On August 5 in Al Arabiya, Hussein Sheikh al-Islam, Iran’s former ambassador to Syria, claimed that Tehran has consistently pleaded with Bashar against his brutal approach to the uprising. This statement, completely incongruous with Iran’s real guidance to the Syrian government, reveals the beginnings of the betrayal moment. With Iran’s newly secured source of influence among militias on the ground, such rhetoric reveals Bashar’s expendability with Iran poised to dominate any transitional process. Tehran will retain control over Hezbollah and the National Defense Forces, thereby maintaining its influence in the country. Hafez warned his son of this threat before he died, long before the revolution. Iran’s wartime alliance with Bashar was never about religious kinship or keeping him in power. It is about controlling Syria, with or without the Assads.

Bassam Barabandi served as a diplomat for several decades in the Syrian Foreign Ministry. This article is a collaborative effort between Barabandi and Tyler Jess Thompson, an international lawyer and Policy Director at United for a Free Syria.

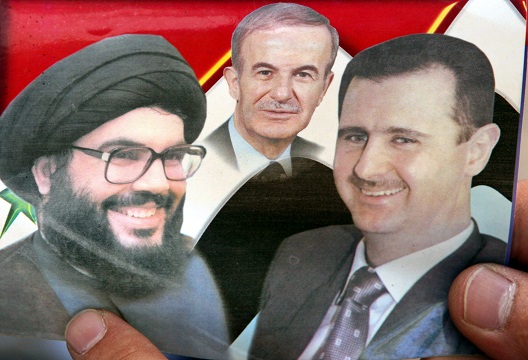

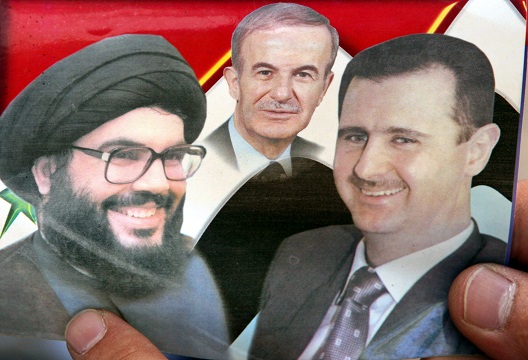

Image: A Syrian street vendor displays a picture of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad (R) , his late father President Hafez al-Assad, and Hizbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah (L), in Damascus June 14, 2006. (Photo: REUTERS/Khaled al-Hariri)