This is our situation in Egypt: a society divided between participators and boycotters, a public that asks what good is participation under unjust rules and the effectiveness of boycotting; citizens whose preferences change by the minute and hour rather than by the day and the week; and a state of constant flux accompanied by fear for the fate of the country and its citizens.

In situations like these, the politician’s main responsibility is to pursue the public good at the expense of narrow (personal or partisan) interests. Another responsibility is to direct citizens to disclose their beliefs and opinions, and announce their intentions, with one of two choices available. On the one hand, they can participate in seemingly democratic mechanisms like elections, the parliament, and elected executive power and pursue reform from within. On the other, they can boycott due to the absence of a democratic spirit and opt to work peacefully outside of institutionalized politics to change the rules for elections, parliament, and executive power. The politician must also disclose his beliefs without claiming to possess a monopoly on the truth and without outbidding those who disagree with him or casting them as traitors. Ultimately participation and boycotting are both legitimate judgments whose results are unknown to all.

In situations like these in which division dominates society, the politician’s responsibility, by virtue of his training and interest, is to search for broad popular acceptance and the people’s confidence. But it is also a responsibility to risk choosing a stance on participating or boycotting even with the knowledge that public opinion is divided, that citizens’ preferences fluctuate, and that those wishing to participate today may not tomorrow; and on the flip side those who currently support the boycott may eventually see participation as the magical solution and those participating as their true representatives. (Those of us who boycotted the first and second Constituent Assemblies have endured all of this, as well as the public’s volatile stance towards us.)

My venture is the following: The rules of the political process are unjust; the essence of its seemingly democratic tools and mechanisms is the antithesis of impartiality and transparency; and human rights are repeatedly being violated. At the moment, I do not believe it is possible to amend these rules by participating in elections and the parliament. The most effective opposition strategy is to boycott and develop a peaceful, comprehensive alternative outside of institutionalized politics.

Therefore, those of us in the National Salvation Front have made the collective decision to boycott the elections, a decision that is consistent with my evaluation and stance. However for the boycott to be successful politically and socially, it must not be limited to a momentary announcement and a non-participatory stance but rather developed into a comprehensive working strategy and positive alternative.

For the electoral boycott to be successful politically and socially – besides the fact the opposition needs to agree that it is the only choice – the boycott must be run as an organized, popular campaign that employs the same tools as electoral campaigns. These tools include organizing public conferences, holding intensive meetings with decision makers and public opinion shapers in different neighborhoods and regions, communicating with the influential economic, financial, and media groups in society, addressing public opinion to explain the motivations for the boycott, and gathering citizens to commit to the boycott once the electoral process starts.

If the boycott is not run as a popular campaign and public support for it is not mobilized, the boycott may remain limited to those political parties and forces that adopted it and the politicians that called for it. If the boycott is not run as a popular campaign, the true (rather than falsified) rates of voter participation in the parliamentary elections could reach their normal values (between 40-50% in the case of Egypt) and thus those who called for the boycott would lose their ability to contest the popular legitimacy of elections on the basis of low voter participation.

For the electoral boycott to be politically and socially successful, it must be tied to realistic strategies to change the unjust rules of the political process that are the primary motive for the boycott in the first place. The goal of the boycott, in turn, is to change these rules from outside of institutionalized politics – outside of the government and Parliament. Our responsibility is to develop strategies and tools for popular and political pressure that achieve the desired change. These strategies and tools must not be limited to repeated calls for demonstrations, protests, and voluntary civil disobedience – despite their importance – and they must not neglect the need for constant communication with the public in order to repeatedly explain the rules which need to be changed and the nature of this desired changed.

We must all be cognizant of the fact that some of those participating in parliamentary elections and institutionalized politics – in the government and the parliament – will also attempt to change the rules of the political process and oppose the dominant Muslim Brotherhood from within, using the tools of legislation, oversight, and enforcement. At times, they will even appear to be more effective then those boycotting. Here, without casting those who participated in the elections as traitors, continuous hard work is necessary to reveal the limitations of the change-from-within strategy and the effectiveness of political and popular pressure to change the rules from outside the political process.

For the electoral boycott to be politically and socially successful, it must also be tied to effective alternatives that are posed to citizens and go beyond merely abstaining from participation in the political process. Wide swaths of the Egyptian people will respond to those who call for a boycott with the essential question: “What then?” We must have a clear response to this question using effective alternatives that open the doors of change in society. Boycotting the elections is a choice to stay away from the power centers of institutionalized politics – the parliament and the government – and opting instead for the ability to influence parliamentary outcomes (laws and government oversight) and government decisions. Our responsibility, therefore, is to offer effective alternatives that depend upon the activity of parties and civil society organizations as well as the media to influence and monitor the government and parliamentary outcomes without directly participating in these institutions and to convince the citizens adopting the boycott that their preferences will be expressed and defended politically in an orderly manner. If those calling for the boycott – parties, organizations, and individuals alike – are capable of delving deeply into society by posing development and lifestyle alternatives for the parts of society hurt by the deteriorating state of affairs and poor government performance, the boycott’s chances for political and social success will certainly increase.

For the electoral boycott to succeed politically and socially, it must be built upon continuous hard work to ensure the popular and organizational effectiveness of the parties and entities that have joined it. Those political parties and entities established to participate in the elections, pursue seats in parliamentary elections, and so influence government action – as well as their grassroots networks and leadership – will be active and their degree of preparedness will be increased during election season and the formation of the parliament and government. Boycotting is always the choice that is the most difficult and threatening for partisan interests. Its unusually high cost translates to the stagnation of grassroots networks and isolation from the street and concerns of citizens. It also ignites conflict between the leadership and different wings within each party. Therefore, when political parties and entities boycott elections, the parliament, and the government, their estimation of the general good and national interest overcomes narrow interests as was the case with the parties that boycotted the farcical 2010 elections. For the parties and entities that are boycotting today for the public good to be able to limit the negative results of the boycott on their constituencies and leadership, the boycott must be run as a continuous campaign and comprehensive alternative that attracts the constituencies of those participating in the elections. Moreover, the parties of the Egyptian opposition must also reconsider their small, varied agendas and think about merging and building entities that are larger, more influential and more widespread.

Amr Hamzawy studied political science and developmental studies in Cairo, The Hague, and Berlin. He joined the Department of Public Policy and Administration at the American University in Cairo in 2011, where he continues to serve today. His academic publications include books on Arab political thought, democracy, human rights and Islamism. He is a former member of parliament and a member of the National Salvation Front.

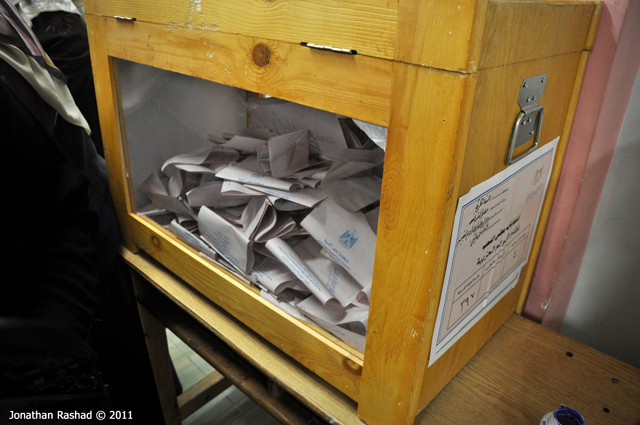

Photo: Jonathan Rashad

Image: Ballot%20Box%20Jonathan%20Rashad.jpg