Not many heads of governments in the Middle East can move swiftly between Riyadh, Cairo, Amman, Ankara, and Tehran, and receive a warm welcome in all those capitals. Iraqi Prime Minister, Haider al-Abadi, followed this itinerary in the last few days, trying to create the image of a competent leader who victoriously took Iraq out of an existential fight with the Islamic State (ISIS, ISIL, or Daesh) and saved its unity from what is perceived in Baghdad as “Kurdish secessionism”. Iraqi senior officials always advocated the idea that a strong Iraq could be a bridge in this highly divided and polarized region, a message Abadi emphasized when he demanded the United States and Iran spare his country the ramifications of their conflict.

However, the United States, Iran, and Saudi Arabia showed understanding for Abadi’s attempted neutrality not because they see Iraq as a bridge, but rather because they believe that it is not strong enough to take a firm position. They know that the Iraqi state is still in the process of shaping itself, and they appear to be trying to influence this process and its outcomes.

Thus, Iraq’s expressed neutrality is not a free choice: it is the only possible position when other alternatives look excessively dangerous. On the one hand, it is risky for Abadi to lose the US support and the newly gained openness from Saudi Arabia and its Arab allies, which he earned by acting as an Iraqi nationalist with appreciable independence from Iran. This image, which distinguished him from his predecessor, helped him secure US support both in the war against ISIS and when he successfully reclaimed disputed territories from the more western friendly government of Kurdistan. On the other hand, it is equally hard for him to be outright hostile to Iran when so much of his actual victories against ISIS and the KRG came through Iranian involvement. Therefore, Abadi is trying to use the US and Iranian support in a measured way to strengthen his position, while resisting pressure from either side when it tries to break this balance.

This delicate situation is going to govern Abadi’s survival and future political career. Two recent events illustrated his attempt to carefully steer this balance, something his predecessor, Nuri al-Maliki, did with relative success during his first term. In a press conference earlier this week, Abadi made unusual comments criticizing those who exaggerated the role of Qassim Suleimani, the Head of the IRGC-affiliated Quds Force, in striking the deal that persuaded the leadership of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) to allow the peaceful redeployment of Iraqi forces in Kirkuk. Without mentioning the name of the Iranian general, he mocked those who thought of Suleimani as a “superman,” insisting that what happened in Kirkuk was an outcome of his declared policy rather than a behind-the-scene set-up of a foreign actor. Not everybody agrees with Abadi’s assessment. For example, the Shi’a politician and former MP, Izzat Shahbendar, insisted during a TV show that the deal with the PUK was masterminded by Suleimani and that Abadi is taking credit because he happened to be the Prime Minister at this time.

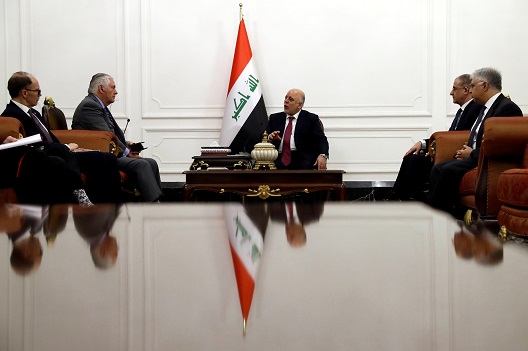

The second event came in Riyadh during a meeting with the Saudi King and the US Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson. The latter called on Iranian militias to leave Iraq as the war with ISIS winds down. Knowing that the description of Iraqi fighters in Popular Mobilization Units (PMU) as Iranian mercenaries would upset his constituency, Abadi’s office rushed to issue a statement asserting that the PMU are patriotic Iraqis who bravely fought ISIS. When he received Tillerson in Baghdad few days later, he made sure to appear on TV with him, reiterating this position while recognizing that there are a few rogue elements in the PMU whose loyalty is not to Iraq and promising to subjugate them to state authority.

Obviously, Abadi is sailing in difficult waters when it comes to dealing with the PMU, an umbrella of diverse paramilitary groups. In Baghdad, it is widely believed that without the PMU, the Iraqi security forces (ISF) could not prevail in the war against ISIS and reclaim disputed territories. Those are groups that by their actions helped build Abadi’s political capital. Nor could ISF succeed without US support, which included arming, training, and air cover, in addition to diplomatic backing. Therefore, Abadi’s hope for now is that neither side will increase the pressure on him to take a position the other side would perceive as a serious threat. It would be problematic for him if the Trump administration intensified its declared policy of pushing back against Iran’s destabilizing role in the region, or if Iran decided to confront an increasingly antagonistic US policy by deploying its resources in Iraq.

Before the next election, Abadi will be trying to strengthen his political stand in two ways. First, by using the political capital he has gained, particularly from the defeat of ISIS and recapture of territory from the KRG. Second, he will continue to build the image of a statesman seeking to consolidate and enforce the state’s legal authority, as he did in the Kurdish referendum crisis. However, for the latter he will undoubtedly have to take a firmer stand against PMU factions whose behavior contradicts and challenges this image of a strong, independent leader. If he choses not to take this direction, he might lose US support, and, with it, the window that opened with Saudi Arabia and other regional countries. This would be a return to conditions like those of Maliki’s last year in office.

The next election will be an important test for Abadi’s political instinct. His main contender will be the Shi’a hardliners that seek a stronger alliance with Iran and take hawkish position towards relations with Sunnis and Kurds. Abadi then must choose between competing with them by being more hardline, or, more likely, building the brand of a statesman who can envision a more constructive approach. For him to succeed, he will need to form alliances, before and after the election, that will allow him to stay in his position despite the opposition of Shi’a hardliners.

At the end, Abadi shares with those Shi’a groups the objective of maintaining the Shi’a ascendancy, which has been reasserted after the defeat of ISIS and the redeployment of ISF and PMU in disputed territories. But for him to be a successful statesman, he will need to use Iraqi nationalism as a narrative to legitimize what Fanar Haddad called the Shi’a-centric state-building. This will require serious attempts to win over those Iraqis who are alienated by the unmitigated Shi’a triumphalism. It is this dynamic of political survival and the rivalry between state-led nationalism and transnational Shiism that is likely to shape Iraq’s future geopolitical stand vis-à-vis other regional powers.

Harith Hasan is a senior non-resident fellow with the Rafik Hariri Center. Follow him on Twitter @harith_hasan

Image: Photo: U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson (2-L) listens as Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi (C) speaks during their meeting in Baghdad, Iraq October 23, 2017. REUTERS/Alex Brandon/Pool