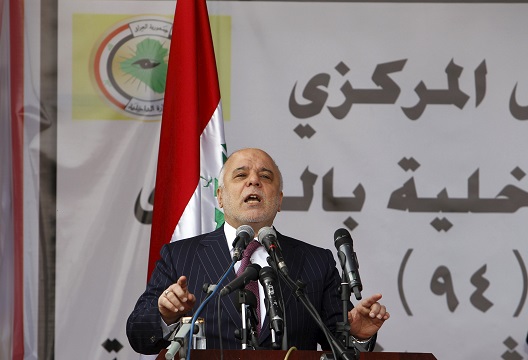

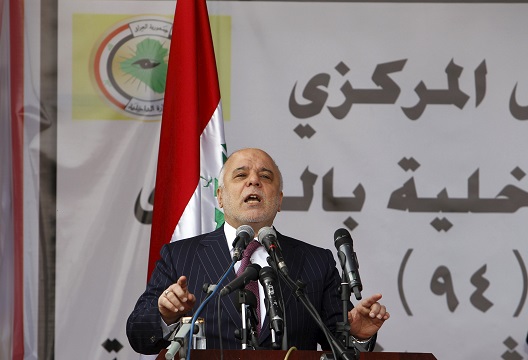

Only a year and half since coming to power in Iraq, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi has failed to learn how to adapt to assure his political survival. Last week, the Iraqi leader announced a new round of radical reforms from a position of weakness, despite having generated a great deal of pushback from Iraq’s political class from his previous attempts to reform the system. On Monday, he exhibited this weakness, signaling a lack of willingness to hold onto his job. “I am ready to leave my post, and I am not holding on to it, but at the same time I am not evading my responsibilities, therefore if they want change, then I am ready for it.”

Only a year and half since coming to power in Iraq, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi has failed to learn how to adapt to assure his political survival. Last week, the Iraqi leader announced a new round of radical reforms from a position of weakness, despite having generated a great deal of pushback from Iraq’s political class from his previous attempts to reform the system. On Monday, he exhibited this weakness, signaling a lack of willingness to hold onto his job. “I am ready to leave my post, and I am not holding on to it, but at the same time I am not evading my responsibilities, therefore if they want change, then I am ready for it.”

Abadi came into office in the summer of 2014 with neither the credibility to make concessions nor the capacity to carry out his political agenda. While a compromised choice between powerbrokers, Iraqi lawmakers who have worked with Abadi during his two terms as a member of parliament describe him as having a “weak personality” and unsavvy political skills, making him less likely to survive the jarring politics of Iraq in the long term.

It is difficult to identify Abadi’s objective given the way he has mismanaged his rule. If his maximalist goal was to consolidate power to become a more effective leader in Iraq’s fragmented polity, he has not brokered the necessary political alliances. If his minimalist goal was to simply survive and preclude the formation of a political coalition that would threaten to unseat him, his actions and rhetoric have unsurprisingly increased the likelihood of that prospect. In short, the Prime Minister’s behavior has amounted to the naive mixture of acting like a man with real power without having much of it.

The reform package, which targets the allocation of ministries to political parties in Abadi’s government, threatens the spirit of power-sharing in Iraq. The initiative appears to be a desperate last-ditch effort to salvage fleeing political support from Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani. While this strategy is imprudent, the rollout and timing is bizarre. Abadi has allowed opposition to build against the pending changes to his cabinet well before announcing the initiative during a televised speech last week, confirming in January rumors that he was planning to reshuffle his cabinet.

Abadi also announced the initiative before an official trip to Europe. A political coup, which despite the rhetoric of “reforms” and “combating corruption” is effectively what Abadi is attempting to do, requires secrecy in planning and swift execution. Instead, he has achieved the opposite on both fronts. “He’s given his opponents a week to strategize,” according to a Reuters report quoting a diplomat in Baghdad. “They may decide it’s in their best interest to keep things how they are and replace him instead.”

The key problem is that Abadi does not exercise enough political authority in Iraq. Despite his position as head of government, Iraq is not a constitutional state; power is not vested in the office of the premiership, but through patronage networks and political alliances on the basis of codependency. Unfortunately for Abadi, Maliki may have ceded his office, but the new prime minister has had to face the legacies of an eight-year regime forged around his predecessor. The last source of power to confront needed to be Maliki; instead, Abadi chose to make him the first.

While not completely successful, Maliki consolidated his government thanks to a US military presence and strong, almost unwavering, support from Washington. When Maliki made a miscalculation, there was little to no costs to his position because the United States was there to bail him out—and Maliki recognized this safety net. This not only occurred following poor decisions and miscalculations on the military battlefield, but also on the political scene as well. On multiple occasions, when political parties threatened to unseat Maliki though a no-confidence vote in parliament, Washington and its diplomats would move in to dissuade those parties from going forward.

Abadi does not have those same assurances that Maliki had enjoyed. His lack of political skill does not bode well for efforts to build a cohesive and strong state. Unfortunately for him, Abadi has not yet learned to maneuver in Iraq’s convoluted power politics. By publicly announcing his plans before securing support behind closed doors—in fact, he often does not consult with any political actors before making a decision—he acts without any political buy-in from Iraq’s traditional power centers. His announcement of a broad and politically sensitive reform package last summer did not involve consultations with any of the Kurdish, Sunni, or Shia parties. In post-Saddam Iraq, there is no more effective a way of engineering one’s political demise.

Not only had Abadi made more of an enemy out of Maliki by moving to abolish his position as vice president last summer, but he has alienated Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, once aligned with him, who threatened to withdraw from the political process if he fails to implement wide-ranging reforms. By setting expectations too high and publicly staking his position before solidifying it, Abadi has essentially placed himself in a precarious lose-lose situation. He has estranged many, while at the same time, become overly dependent on others. Not only has Abadi exposed his intentions to his rivals, effectively making them permanent rivals, but also exposed his increasing dependency on temporary allies, who will no doubt take advantage of his weakened circumstance.

Indeed, while Sadr and Maliki are rivals themselves within Shia politics, the former is likely placing added pressure on Abadi now for the usual gamesmanship reasons played in Iraq: (1) to extract greater concessions from the prime minister given his increasing dependency, and (2) hedging bets in case Abadi fails to meet expectations, thereby saving face and benefiting in symbolic politics. If Abadi fails, Sadr can claim that he did not do so with his support, but rather because of the absence of his support.

Abadi also lacks the close networks to build administrative capacity. His inner circle remains small. Prematurely going after Maliki’s position split the Da`wa party (to which Abadi also belongs), leaving little political foundation on which to rely. With no trust in the political infrastructure, his current advisors refuse to reallocate responsibilities, power, and access to others. This dynamic has restricted Abadi’s managerial capacity, limited access to the lever of power, and led to poor and opaque decision-making.

Abadi was an unknown player when the Islamic State (ISIS or ISIL) swept through large parts of the country in 2014. Washington had little knowledge of how he would fare as a politician occupying the most demanding position in an unraveling Iraq. Today, with empirical evidence of his performance, the White House continues to place its bets on a man who does not have the political authority within his own party, let alone within his own government. Nonetheless, the United States continues to pressure him to redistribute power and reform an entrenched political system with neither appreciation for his precarious position, nor a recognition that his influence in Iraq is too weak to provide political protection. Even if Abadi survives this round, he will remain in a dangerous position politically for some time to come.

Ramzy Mardini is a Nonresident Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

Image: Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi speaks during the Iraqi Police Day at a police academy in Baghdad January 9, 2016. (Reuters)