The city of Aden was ostensibly the only part of Yemen where post-conflict reconstruction was viable, especially since the area of the conflict has been declared a Houthi-free zone since July 22, 2015. Subsequently, the residents of the city were seemingly united in that the majority are southern, Sunni, and anti-Houthi/Saleh. But now the conflict is occurring amongst Aden “allies,” not just nationally but regionally as well, as they are now divided based on the claim that President Abdrabbo Mansour Hadi’s government is “corrupt.”

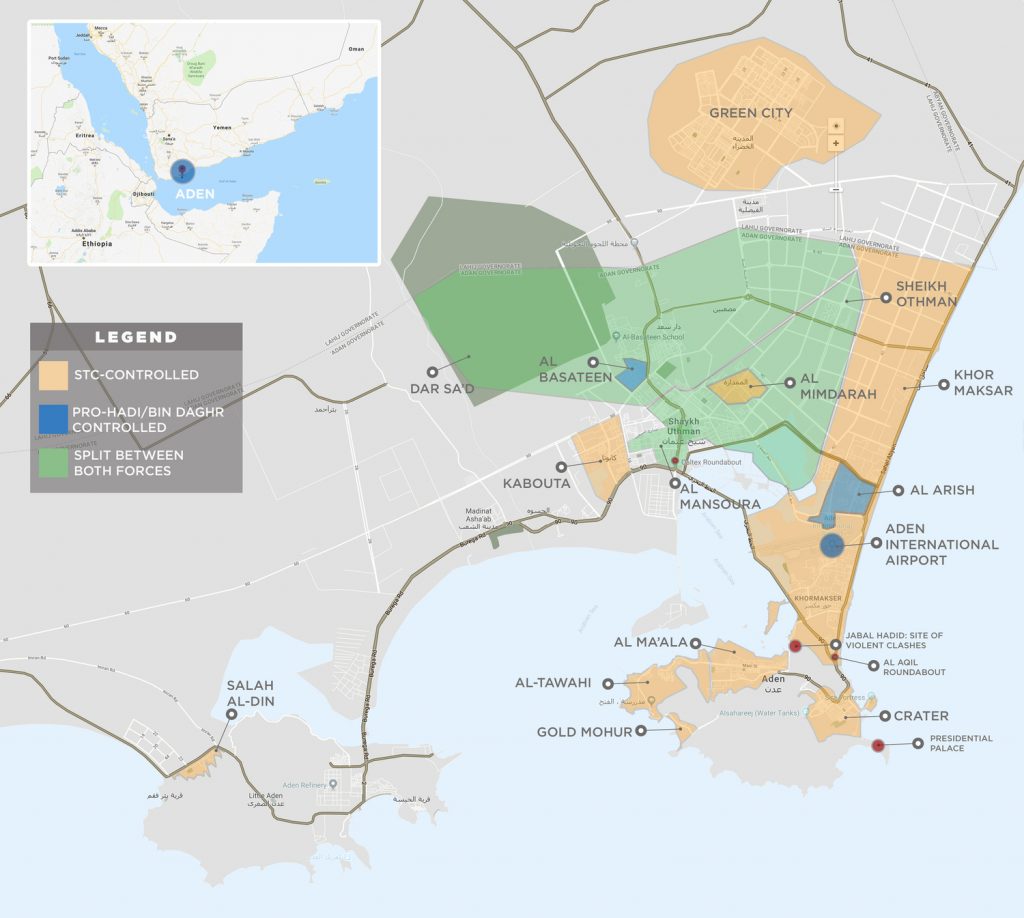

In a matter of days, the Southern Transitional Council (STC), surrounded the internationally recognized administration in al-Ma’sheeq neighborhood and seized the city except for the presidential palace. The STC is the latest group to emerge under the umbrella of al-Hirak al-Janubiye or the Southern Separatist Movement, and this strife is an attempt to coerce the president into replacing the current government and to reject the presence of northern figures in the south.

Forty deaths have been reported so far in a power-struggle between southern forces backed by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) over the quintessential issue of whether southern Yemen will secede. In the past few days, the STC aggressively asserted their influence in the south but stopped short of declaring President Hadi himself “illegitimate.”

The STC’s criticism of the government is not unfounded. The Yemeni Rial has lost over 130 percent of its value since the Arab Coalition began its war in Yemen in 2015. This, coupled with the Hadi government’s inability to restore normalcy to the city of Aden, caused the STC to hold a conference on January 25 during which they instructed the president to remove Prime Minister Ahmed Bin Daghr.

Photo: Map of Aden as of January 31, 2018.

Originally from the South himself, Hadi appointed mostly southern figures since 2015. Some of these figures are separatist hardliners, a move by Hadi to appease the separatists and control the south after driving out the Houthis. During this time, elements of al-Hirak Movement developed a close affinity with the UAE. In April 2017, for undisclosed reasons, Hadi decided to appoint new government officials in the south. Removed officials joined forces to form the STC.

The STC counts among its members former senior officials, including the governors of al-Dhale’, Shabwa, Hadhramout, Lahij, al-Mahrah, and Socotra governorates. The Chairman is Major General Aidarus al-Zoubaidi, the former governor of Aden (December 2015 until April 2017) and former militia leader in al-Dhale’. His deputy is Hani Bin Breik, a southern separatist and head of a popular Salafi movement in the South. They represent grassroots leaders from the al-Hirak.

The Southern Separatist movement developed after the 1994 civil war between the north and the south of Yemen. It gained steam in 2007, when Jam’iyat Abna’ Radfan, or the People’s Assembly of Radfan, proposed unifying various southern separatist movements to strengthen the overall cause. In 2011, the revolution strengthened the Southern Separatist movement with efforts to drive out the late former President Ali Abdullah Saleh. Saleh’s approach to unifying Yemen had the opposite effect: instead of bringing people together, he exacerbating differences by trying to control the country through political and tribal alliances.

Today, the STC carries the torch for al-Hirak, demanding a clear direction towards secession in any future agreement and does not want any northern powers to be present in the south. However, the Hadi-government wants to keep the image that Aden will be one of the federal regions in a united Yemen based on the outcomes of the National Dialogue Conference. Some political parties, for example Islah and some elements of General People’s Congress (GPC), support the government’s claim that Yemen should stay united.

While unity is the most favorable outcome for Yemen, the so-called Arab-backed coalition is now splintering and fighting amongst each other in the south. Put differently, the Arab backers are settling some disagreements regarding their geopolitical interests through Yemen proxies. It is not a full-on war, but it is a bloody display of power between STC and the “legitimate” government on the ground. Left to its own devices, the government would have easily lost its hold on the country had it not been for international backing.

This is not the first time that Hadi and his government are instructed on their actions . Ever since Hadi assumed his current position, he has failed to create a government that is able to provide adequate services and respond to grievances. In 2012 when he became president, various governors and governmental employees on the local level and loyal to former President Saleh, refused to hand over power to their successors. During the Houthi Crisis, and under the guise of corruption and inflation, the Houthis capitalized on popular sentiments to capture Sana’a.

Once the south was considered a Houthi-free zone, the president failed to return to Yemen, instead staying in Riyadh; though some reports say he is under house arrest. Even now, after the STC secured Aden, Lieutenant General Mahran al-Qubati, Commander of the Presidential Guard, stated that government forces had regained control of the Dar Sa’d northern barracks in Aden due to direct Saudi intervention. It is unlikely that the alliance between the UAE and KSA will disintegrate over this power struggle, but it is clear that both states won’t hesitate to use Yemeni partners on the ground to gain the upper hand.

The Arab Coalition’s vision is for a future Yemen inconclusive. The UAE, on one hand, formed a genuine alliance with Yemeni troops and have invested in the rebuilding of Aden beyond pledging large sums of money. They feel that they should have a larger stake in what happens and should be able to determine with whom they form political alliances. It also seems that Yemen’s unity is not their prime concern. The KSA, on the other hand, has adopted the United Nations narrative and would like to continue the transitional process that began after the revolution in 2011 but before the war in 2015. Beyond countering the presence of Iran in Yemen by restoring the “legitimate government” in Yemen, it is unclear what KSA’s objectives are but to maintain the UN narrative that Yemen must be one state.

This is not the first time that Yemenis signal to the international community that the government of Yemen needs to be recognized locally, by northerners and southerners alike. Unless a new government is formed that is capable of providing public services and responding to the people’s demands, there will be no faith between the people and the state. In the next few years, Yemen will scramble to deal with an unprecedented humanitarian crisis, and unless the government is up to the task, Yemenis will only continue to suffer. Ruling exclusively by decree won’t suffice as it will only allow for non-governmental bodies to spread and gain more influence in a fragile Yemen.

Sama’a Al-Hamdani is a consultant with the Rafik Hariri Center. She is the President of the Yemen Cultural Institute for Heritage and the Arts. Follow her on Twitter @Yemeniaty.

Image: Photo: A bodyguard of a southern Yemeni separatist leader holds an RPG launcher as he rides on the back of a pick-up truck at the site of an anti-government protest in Aden, Yemen January 28, 2018. REUTERS/Fawaz Salman