Questions of decentralization pervade policy debates in Libya. After decades of harsh and highly centralized rule under Muammar Qaddafi, policymakers, scholars, and civil-society activists are contemplating how to unpack state authority to empower cities and regional development. The transitional government has encountered challenges of decentralization in passing a local governance law regulating municipal councils across the country in attempting to consolidate militias with regional and tribal affiliations. Demands of political groups in and around Libya’s eastern province (including Benghazi), long neglected by the Qaddafi regime, won them equal representation in the upcoming constituent assembly despite dramatic differences in population size. Decentralization is shaping up to be a defining feature of the constitution-making process, and yet there is little knowledge about options available in designing a decentralized system. The debate on decentralization exists at the level of semantics, creating conflict-prone binaries like federal or anti-federal that offer little nuance and distract from alternative solutions to an ideal solution for Libya.

Questions of decentralization pervade policy debates in Libya. After decades of harsh and highly centralized rule under Muammar Qaddafi, policymakers, scholars, and civil-society activists are contemplating how to unpack state authority to empower cities and regional development. The transitional government has encountered challenges of decentralization in passing a local governance law regulating municipal councils across the country in attempting to consolidate militias with regional and tribal affiliations. Demands of political groups in and around Libya’s eastern province (including Benghazi), long neglected by the Qaddafi regime, won them equal representation in the upcoming constituent assembly despite dramatic differences in population size. Decentralization is shaping up to be a defining feature of the constitution-making process, and yet there is little knowledge about options available in designing a decentralized system. The debate on decentralization exists at the level of semantics, creating conflict-prone binaries like federal or anti-federal that offer little nuance and distract from alternative solutions to an ideal solution for Libya.

A new report on decentralization in Libya attempts to move the debate from labels to policy options. The report, published in two languages by Democracy Reporting International, the University of Benghazi, and the Sadeq Institute, encourages Libyans to have a sophisticated debate on the elements of the distribution of power and leave it to academics to classify the result as decentralized or federal. The approach of leaving labels at the door encouraged progress in transitional contexts of Sudan and South Africa. The report introduces theories of decentralization and a survey of related constitutional options that might be helpful to members of or advocates to the future constituent assembly. It concludes with fifty questions related to decentralization and commentary by two Libyan coauthors. The questionnaire represents a living document to be presented to the constituent assembly; further commentary, in Arabic or English, is welcome at libya@democracy-reporting.org.

At the core of the decentralization debate is Libya’s history of deinstitutionalization, which Dirk Vandewalle, a leading expert on Libya, has argued is rooted in the founding of the country in the 1950s. Libya’s first constitution crafted a kingdom out of three Ottoman provinces turned Italian colonies. Before this, Libya had not existed as a unified entity. A new constitution was drafted with equal representation from each of the three provinces, and a federal pact was established whereby each of the provinces retained sovereignty over a defined set of policy areas. The federal system was abandoned by constitutional amendment in 1963, which created a unified state and ten governorates. Six years later, Qaddafi took power in a coup and centralized the state even further, establishing a system overlapping and contradictory networks with no common hierarchy, except that Qaddafi was always at the top. The Qaddafi system effectively destroyed the sub-national government and relied instead on competing municipalities. Municipalities, tribes, and even families raised their own militias during the revolution that toppled Qaddafi. These militias, Libya’s only source of internal security, often engage in bloody disputes with each other over grievances from the civil war, smuggling routes, and accusations of affiliations with Qaddafi. Given Libya’s entrenched sub-divisions, report coauthor Professor Mansour Elbabour has eloquently called Libya a “nation of cities.”

The current legal framework in Libya, and the design of the constitution-making process, does little to address these problems. The local-governance law has yet to be fully implemented as the budgets of elected municipal councils are still controlled by the central Ministry of Local Governance, in Tripoli. The east still complains of neglect, and some have called for the separation of the east from the rest of Libya. (A nationally representative and methodologically rigorous survey done by the University of Benghazi shows that support for federalism is in fact quite low—at only 8 percent nationwide and 15 percent in the east.) Furthermore, the sixty-member constituent assembly attempts to satisfy regional demands by drawing twenty members from each of the three historical provinces, as was done in 1951. But the nature of regional conflict has changed, whereby some of the most intense conflicts occur between cities from within the same province, such as Misurata and Zintan. The 20-20-20 arrangement is a 1951 solution to a 2013 problem.

The members of the constituent assembly will have to reckon with an intensifying debate around decentralization characterized by a lack of sophistication, historical mistrust, and tremendous consequences for stability. A debate around policy options best for Libyans, as opposed to conflict-ridden semantics, is prudent.

Duncan Pickard is Libya country director at Democracy Reporting International and a nonresident fellow at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. The views expressed here are his own.

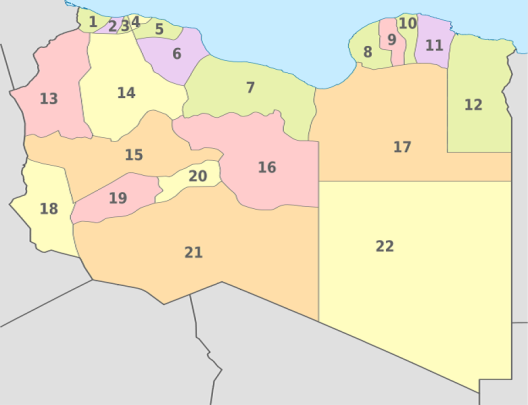

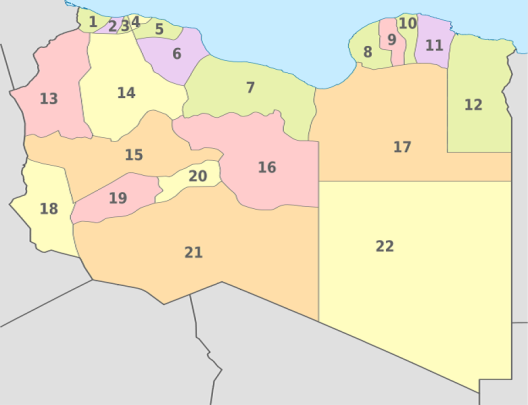

Image: Libya's administrative districts. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)