In two weeks, Egyptians are expected to turn out in unprecedented numbers for the country’s first ostensibly free and fair elections. But while Egypt’s rapidly proliferating parties are enthusiastically campaigning for seats in the post-Mubarak parliament, recent changes to the electoral system may have troubling implications for the political diversity and legitimacy of the next elected People’s Assembly. Under growing pressure from new political parties that fear exclusion from a parliament dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood and resurgent NDP remnants, the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) has made several rounds of revisions to the electoral system in recent months, including the geographic expansion of voting districts. While it is impossible to predict what impact these changes might have on the election results, the amendments have only added to the confusion surrounding an already complex and opaque electoral system and could disadvantage candidates from smaller parties that lack the resources to compete effectively against wealthier rivals in larger, more populous districts.

Although Egypt’s political scene is more diverse than ever – at least fifty-five new parties have formed since the revolution – most of these nascent political forces are likely be shut out of next political system in the face of stiff competition from the Muslim Brotherhood and NDP remnants. Ten months after the revolution, Egyptians are finally on the verge of electing a civilian government, but there is no guarantee that November elections will produce the genuinely representative leadership that was envisioned by protesters in Tahrir Square.

Quick Facts about the Current Electoral System:

- Available seats: Candidates will compete for 498 seats in the People’s Assembly (lower house) and 270 seats in the Shura Council (upper house). The SCAF will appoint up to 10 additional members of the People’s Assembly and 90 members of the Shura Council.

- Timeline: Polling for the People’s Assembly will be conducted in three stages, starting on November 28 and ending on January 10. Shura Council elections will run from January 29 through March 11.

- Candidates and parties: At least 15,000 candidates have registered for the People’s Assembly and Shura Council elections, both as independents and as party-based nominees. Over 55 political parties have registered for elections, at least 35 of which were formed after the January uprising.

- Electoral system design: Mixed system for both the People’s Assembly and Shura Council in which two thirds of the seats will be allocated through a list-based proportional representation system and one third through a majoritarian individual candidacy system. Both independents and party-based nominees may compete for the individual candidacy seats.

- Farmers/workers quota: At least 50 percent of all People’s Assembly and Shura Council members must be farmers or workers.

- Women’s quota: There must be at least one female candidate on each party’s list for a given district. This requirement has replaced the Mubarak-era gender quota that reserved approximately 12 percent of the parliamentary seats for women.

The Pre-revolutionary Electoral System:

Much of the pre-revolutionary electoral system outlined in the now-defunct 1971 Constitution remains intact, although significant changes have been introduced that may impact the representation of women, religious minorities and minor political parties. Under the voting system that was in place for the last round of parliamentary elections in November 2010, 508 of the 518 seats were filled through two rounds of voting in two-member districts through a majoritarian individual candidacy system, with the remaining ten seats filled by presidential appointees. In 2010, the NDP also introduced a 64-seat quota for female representatives. Although this decision was hailed by international observers as a victory for women’s rights, it was primarily motivated by the ruling party’s desire to further consolidate an already overwhelming parliamentary majority by padding the People’s Assembly with female NDP loyalists. The 1971 Constitution also reserved fifty percent of the People’s Assembly seats for workers and farmers, a relic of the Nasser system that has been preserved in the current electoral system.

Timeline of Electoral Law Amendments:

- May 30, 2011: A new draft electoral law introduced by the SCAF in May 2011 outlined a hybrid system in which two thirds of the People’s Assembly seats would be filled according to the existing two-member district, individual candidacy system (preserving the fifty percent quota for farmers and workers), while the remaining third of seats would be allocated through a closed-list proportional representation system. New and liberal political parties immediately criticized the draft, claiming that the individual candidacy system had facilitated ballot fraud and voter intimidation under Mubarak’s rule and would likely give an unfair advantage to independent candidates affiliated with the NDP.

- July 7, 2011: The interim government approved additional amendments to the People’s Assembly Law and Shura Council Law setting the number of seats in the People’s Assembly at 504 and the number of Shura Council seats at 390. Most importantly, the revisions restructured the electoral system in response to widespread criticism of the individual candidacy component. Under the revised law, 50 percent of the seats would be allocated through the proportional representation system while the remaining 50 percent would be allocated through the individual candidacy system.

- September 25, 2011: A new round of amendments introduced in September 2011 significantly altered the structure of the system again, in an attempt to accommodate smaller and secular parties that feared a sweeping victory by former NDP candidates in races contested through the individual candidacy system. Under the latest amendments, only a third of the seats would be allocated through the individual candidacy system, while two thirds would be decided by the proportional representation system. Despite the reduction in individual candidacy seats, most parties continued to criticize the electoral law and Article 5 in particular, which barred political parties from fielding candidates for the third of seats to be allocated through the individual candidacy system. The two most powerful electoral coalitions, the Egyptian Bloc and the Brotherhood-dominated Democratic Alliance, both rejected the amendments, claiming that Article 5 would marginalize parties and open the door for NDP-affiliated candidates to sweep the seats reserved for independents.

- October 9, 2011: After the Democratic Alliance and several other parties threatened to boycott the elections, the interim government agreed to remove the controversial Article 5 from the electoral law, allowing parties to compete in the individual candidacy races.

Potential Consequences of the Electoral System:

Given this rapid succession of amendments, voters are parties are struggling to keep up with the evolution of an opaque and highly complex electoral law. With just two weeks remaining before the start of elections on November 28, criticism of the electoral law remains widespread, and voters fear that the system will not only allow NDP remnants to gain a foothold in the next parliament, but will also marginalize minority and female candidates. The current design of the electoral system could lead to several adverse outcomes:

- NDP bias: The latest amendments to the electoral law leave open a window of opportunity for former NDP candidates — most of whom are running as independents — to dominate the individual candidacy races in districts where the former ruling party’s patronage networks and power base are still intact, even though the elimination of Article 5 has opened the 83 individual-candidate seats to contestation by parties as well as independents. Although an administrative court in Mansoura issued a decision on November 11 banning former NDP members from competing in the upcoming elections, the ruling is geographically limited in scope — applying only to the governorate of Dakhaliya — and the mechanisms for enforcement remain unclear. Meanwhile, other courts have been sympathetic to the NDP: On November 13, an Alexandria judge threw out a case seeking to ban former NDP member Tarek Talaat Mustafa from competing in elections on and upheld his right to run for parliament.

- Marginalizing women and minorities: In races determined by proportional representation, female and minority candidates are inevitably placed low on party lists, virtually guaranteeing their defeat. The removal of the 64-seat quota for women has further disadvantaged female candidates.

- Security challenges: Under the highly complex electoral system, elections will be dragged out over a period of three and a half months in three separate stages, posing a daunting administrative challenge to the judiciary body (Higher Electoral Commission) responsible for supervising elections as well as the security forces tasked with maintaining order. The individual candidacy system has historically been criticized for encouraging violence, as it leads to highly personalized contests in which independent candidates could resort to hiring thugs or other dangerous strategies to intimidate rivals. Another factor increasing the likelihood of violence and misconduct at polling stations is the large size and diversity of electoral districts, which were reconfigured in the round of amendments issued in September 2011. The redistricting process significantly decreased the number of constituencies from 222 to 126 for the individual candidacy races, with 58 constituencies reserved for the proportional representation system, at least doubling the geographical size and number of voters for each district. By increasing the volume and diversity of voters at individual polling stations, the enlarged districts will likely lead to intensified competition and even violence between rival political forces.

- Campaign spending: The creation of larger, more populous districts will require candidates to spend more money on campaigning and voter outreach, giving a significant advantage to the Muslim Brotherhood and former NDP candidates who possess the resources and patronage networks to mobilize voters. Smaller parties that lack deep pockets and well-established constituencies will have difficulty competing in an electoral system that favors the wealthiest candidates.

- Pitting Islamists against Secularists: The structure of the electoral system is likely to intensify polarization between Islamist and secular political forces, as the weaker parties in each camp are forced to form ideological alliances in order to run viable campaigns in enlarged districts that require increased spending and voter outreach efforts. Egyptian political scientist Mazen Hassan predicts that the Muslim Brotherhood will be the primary beneficiary of this polarization trend, as individual candidates will not be able to win in larger, more populous districts solely on the basis of their popularity and personal networks without the backing of the Brotherhood or another party with the resources and campaign apparatus to support multiple candidates.

Whether these factors will conspire to undermine a clean and transparent polling process remains to be seen, but the complexity of the electoral system certainly will not make a successful democratic transition any easier.

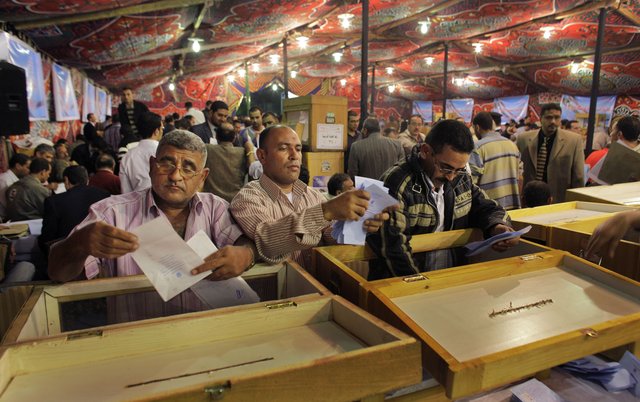

Image: Egypt%20voting_0.jpg