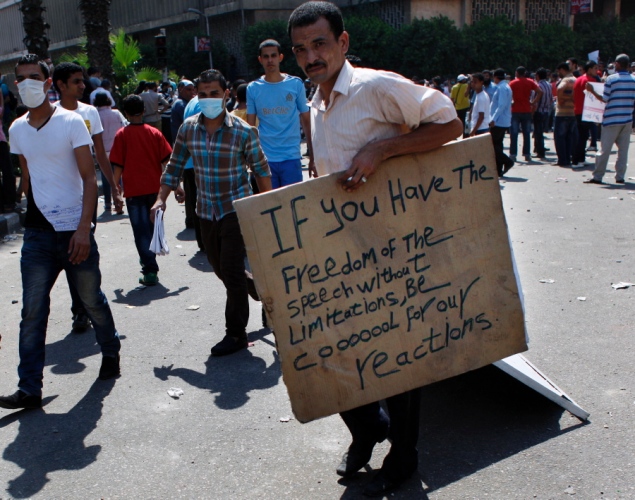

‘Innocence of Muslims’, the film that sparked a wave of violent protests across the Middle East is not the first work of its kind, deemed an unacceptable violation of religion by Muslims, while the west defends it as an example of freedom of expression. For the most part, protests of this kind are a simple expression of anger, but in some cases they tip over into an expression of violence. Last week, the latest of this kind of violence claimed the lives of the American ambassador to Libya and three embassy staff members. In Cairo, it led to the taking down the American flag and replacing it with that of al-Qaeda. These protests are a link in a long chain of similar incidents, like those sparked by the Danish cartoons in 2005. At times like this, it is worth considering the underlying causes of this anger.

The Wahabi Salafist school of thought, largely funded by oil-rich Arab countries, promotes Islamic fundamentalism and reinforces its presence, particularly when the religion is perceived to be under attack. Military dictatorships which employ religious rhetoric also play a role, as does the nature of the Muslim communities where these protests take place. Often these communities are part of conservative, patriarchal societies which insist upon upholding tradition and respecting that which is deemed holy. Some of it can also be explained by pure political exploitation, with religious sentiments stoked by the media and political parties in order to further their own interests, or to distract the public from more important issues.

However, an often ignored reason is a fear for Islam. There is a belief amongst Islamic movements, particularly the Salafists, that there is a conspiracy against Islam and that it is in danger. The mindset that Islam is under threat dates back to the start of the globalization era and the information revolution in the mid-1990s. The United States’ war on terror furthered this notion, especially under the Bush administration, which initially conflated Islam and terrorism and only later tweaked its rhetoric so as to differentiate between Islamist extremists and Muslims.

This fear prompted extremist groups to label the US as Islam’s primary enemy driven also by US support for Israel and its perceived anti-Islamic stances. At the same time the phenomenon of Islamophobia began to take form in the West. 9/11 represents just one of the manifestations of this conflict and further fueled fears on both sides – the fear for Islam and the fear of it.

The appearance of Arabic-language evangelizing Christian channels devoting significant airtime to aggressively criticizing Islam reinforced these concerns over the state of Islam. The most famous of those channels was the US-based Al Hayat, which broadcast programming with searing criticisms of Islam by excommunicated and exiled priest Zakaria Botros. These channels, together with the establishment of similar Islamic counterparts, all contributed to the sectarian climate in many Arab countries and have likely contributed to higher numbers of incidents directed at Christian minorities in the Arab world, particularly in Egypt and Iraq.

Fear for Islam has manifested itself in other ways in Egypt, away from accusations of blasphemy. Following the January 2011 uprising, a concern for the preservation of the country’s Islamic identity was one of the driving factors behind political maneuvering in Egypt, and led to the political polarization of Islamists and secularists. Some Egyptians hoped that after Mubarak’s fall, Egypt would be on a path to democratic transformation. Islamists feared the impact that a democratic transformation would have on the country’s Islamic identity.

The first manifestations of these fears emerged during the March 2011 referendum regarding the constitutional amendments. Political forces split into two factions, the Islamists and the liberals. The Islamist faction was in favor of the amendments put forward by the constitutional committee, claiming that if liberals had their way, Article 2 would be stricken from the constitution. The liberal faction, on the other hand, held that an orderly transition to democracy required that the constitution be written first, and were thus opposed to the constitutional amendments.

Recently, this fear also prompted Salafists to propose a new article in the constitution a few days before the protests, criminalizing the defamation of religion. This may have been a major factor in the strong Salafist presence in the protests on September 11.

As the protests continue to spread further east into Pakistan and Afghanistan, the same rule of fearing for their religion, together with an already openly hostile attitude towards the US throughout the region will continue to give rise to angry protests. Turning an eye to the Middle East, given that no genuine liberal democracy guaranteeing the freedoms of expression and religion has emerged from the Arab Spring, the current climate which stokes the notion of a clash of civilizations is likely to fester.

Magdy Samaan is a visiting fellow at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East and a 2011 MENA Democracy Fellow at the World Affairs Institute.

Photo Credit: Nasser Nasser/AP

Image: Nasser%20Nasser.jpg