In the summer of 2011 Sayed al-Essawi, an Egyptian man claiming superhuman strength, briefly made international news when he challenged a lion to a death match. The bout—which al-Essawi described as a means to revive Egyptian tourism and prove that man is stronger than lion—was anticlimactic. With cameras rolling, Essawi shuffled around an oversized cage and, clutching a satellite dish jury-rigged into a shield, taunted a visibly disinterested lion. Several minutes into the “fight,” neither party had thrown a punch. Al-Essawi backed out of the cage and, for reasons not totally clear, declared total victory.

In the summer of 2011 Sayed al-Essawi, an Egyptian man claiming superhuman strength, briefly made international news when he challenged a lion to a death match. The bout—which al-Essawi described as a means to revive Egyptian tourism and prove that man is stronger than lion—was anticlimactic. With cameras rolling, Essawi shuffled around an oversized cage and, clutching a satellite dish jury-rigged into a shield, taunted a visibly disinterested lion. Several minutes into the “fight,” neither party had thrown a punch. Al-Essawi backed out of the cage and, for reasons not totally clear, declared total victory.

After the stunt, al-Essawi largely disappeared from public view—until recently, when the former lion fighter re-emerged in his hometown of Mansoura, this time wearing the hat of aggressive anti-Brotherhood vigilante. How residents view him and his vigilantism has become a sort of Rorschach test for the city’s complex views toward the Brotherhood, a group that has historically found a strong base of support in the Delta city.

The Battle of Port Said Street

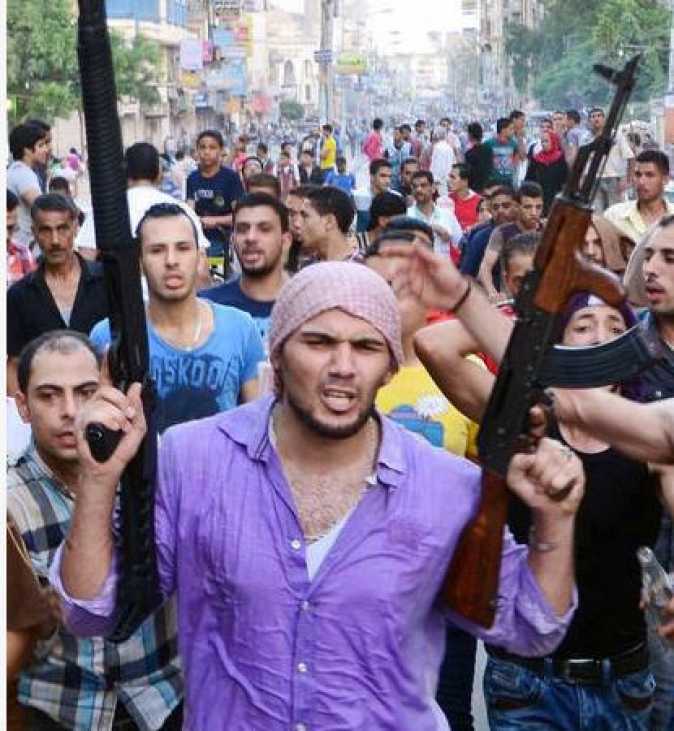

On June 26, while then-President Mohamed Morsi was busy preparing a speech to resuscitate his anemic administration, violent clashes broke out in Mansoura. Later dubbed the Battle of Port Said Street by locals, intermittent fighting spanned three days after a pro-Brotherhood march of several thousand met fierce resistance from shopkeepers and myriad opponents on Port Said Street (hence the name). Accounts vary widely, but several were reported dead, as many as 251 injured, and a number of shops destroyed. Shorouk, an Egyptian daily newspaper, called the Mansoura clashes a “preview” of what might be in store for the country “should fighting break out between supporters and opponents of the president.” Curiously, one photo in particular from the events went viral in Mansoura:

Pictured above is al-Essawi, the lion fighter, who before dueling with animals was known in Mansoura as a human weapon of the former regime—essentially an intimidator for hire whenever the occasion called for one. Some in Mansoura refer to him as “leader of the thugs.”

During Morsi’s June 26 speech, just hours after the Battle of Port Said Street broke out, the president denounced, among many other things, individuals he claimed were hiring thugs to spread violence. Somewhat surprisingly, Morsi called out two of these perpetrators by name, one being Wahid Fouda of Mansoura.

Fouda has long ties to the former Mubarak regime’s party, the National Democratic Party, and in 2011 nearly took one of Mansoura’s parliamentary seats before losing a closely contested run-off against the Brotherhood. This last anecdote should give you some sense of where the city stands politically: even when the Brotherhood was at the peak of its popularity in 2011, the former regime had significant strength.

When people in Mansoura talk about the still-powerful political presence of feloul (former regime remnants) they often refer to Fouda; when people talk about the regime’s hired thugs, they often reference al-Essawi. Whether or not al-Essawi actually takes money from Fouda is almost beside the point—the two men are linked in the minds of the city’s residents and represent symbols of the former Mubarak regime. During the battle of Port Said, al-Essawi took a lead role in violently dispersing the Brotherhood’s march and was hailed as bringing opponents of Morsi to “victory.” According to eyewitnesses, on June 30 al-Essawi was embraced with a hero’s welcome in the city’s main square.

Put differently, many Mansoura residents, perhaps some more consciously than others, were cheering on the triumphant revival of the former regime.

Vigilantism Post-June 30

Like elsewhere in Egypt, tensions between Brotherhood supporters and opponents has only increased since the removal of Mohamed Morsi. A staple of life in Mansoura has been vigilante justice and clashes between ordinary citizens.

Brotherhood marches that degenerate into street fights, injuries, and sometimes deaths, have become a fairly regular occurrence. On August 16, when one such march descended into violence, a resident who came out to protect his property was killed in the ensuing crossfire. His portrait now hangs solemnly over the street. The following Friday Brotherhood opponents set the Mansoura Freedom and Justice Party headquarters on fire. Though anti-Brotherhood sentiment exists on a national level, some incidents look remarkably like retaliatory acts carried out in response to local conflicts.

Like al-Eissawy’s thuggery—which the Brotherhood claims is responsible for seven of its supporters’ deaths since June 26—violence in the city has generally gone unpunished when directed against the Brotherhood, who the police see as their primary opponents. This selectively laissez-faire police work has allowed vigilantism—and polarization between the two sides generally—to flourish.

“There’s been a wave of violence that has taken place between the two sides, shops burned, Brotherhood homes broken into, and people from both sides have died in clashes. Relative to what you see in other governorates, the violence between people here has been particularly high,” says Ayman al-Diasty, media spokesperson for Mansoura’s April 6 Movement.

According to al-Diasty, the polarization is only getting worse each day.

“It’s gotten to the point where, at the hospital where I work, they notified people they are prohibited from talking about politics. This came after an incident where a fight broke out between two doctors in the same department, one a supporter, the other an opponent of Sisi,” he says.

The Limits of Brotherhood Repression

Tit-for-tat violence is of course just one side of Mansoura’s story, and left in isolation would do injustice to the complex relationship most residents have with their Brotherhood neighbors on a local level.

With Egyptian television racing to paint the Brotherhood as terrorists in the broadest of strokes, it is easy to forget that its members are often engaged in social circles far beyond the organization itself. Because of this, the state is not always immune from public backlash when it cracks down—every arbitrary Brotherhood arrest risks the possibility of alienating a large swath of that individual’s community. This is perhaps why demonizing the organization is a key tactic in the first place, and why allowing for vigilantism—which takes the heat off the state—is sometimes preferable to actual police work.

Local Brotherhood leaders in Mansoura have, as elsewhere, been the target of mass arrests. At least some of these arrests are beginning to elicit sympathy from those who might normally oppose the organization.

Following the ‘Friday of Rage’ demonstrations on August 16, six doctors associated with the Brotherhood were arrested. The most famous, Ibrahim al-Iraqi, is a well-known professor in the faculty of Medicine at Mansoura University (al-Iraqi was nearly elected university president in 2011). When Ibrahim’s son, Ahmed al-Iraqi, went to visit his father at the police station, he too was detained. Students and faculty at the College of Medicine—Brotherhood supporters and opponents alike—have begun demonstrating regularly to protest the arrests.

Ahmed Othman, a participant at the demonstration, told a local Mansoura news website, “We want to send a message to people that those being jailed are just regular people and doctors taken from their homes.”

To avoid arrest, the Brotherhood’s more prominent members have gone into hiding. Sobhi Attiya, a professor of history and dean at Mansoura University’s College of Tourism, was appointed Governor of Daqahlia just two weeks before Morsi was removed from office. Some time after June 30, Attiya disappeared from public life.

Samah el-Saied, a vocally anti-Brotherhood colleague of Attiya’s at the university, nevertheless grows despondent when considering Attiya’s absence from university life:

“He is a very respectful person – he’s really good. He’s a good professor and doesn’t deserve to be arrested. I don’t think the people who have been arrested in Mansoura deserve to be.” Referring to al-Iraqi, al-Saied continues, “Even if they belong to the Brotherhood, their sons have nothing to do with this.”

Debating the Legacy of a Lion Fighter

On August 7, Sayed al-Essawi approached a Brotherhood demonstration for what appears to be the last time. Al-Essawi, flanked by a small group of supporters, was armed with bird shot and preparing to break up the Brotherhood rally when its supporters allegedly opened fire, hitting him with five bullets. One of the rounds lodged into the back of his neck, leaving the man who once boasted of superhuman abilities paralyzed from the waist down.

Media coverage of the incident was as varied as the feelings local residents had for him. Some framed it as an assassination attempt on the revolutionary and heroic lion fighter, others as the fall of the city’s biggest thug.

Al-Essawi represents the most extreme version of the city’s surging vigilantism, and local support for him is at least partially a reflection of the state’s ability to demonize the Brotherhood. Many in Mansoura can simultaneously recognize al-Essawi as a symbol of the dark side of the Mubarak regime—repression through pure force—and tout him as a hero for his fight against the Brotherhood. In this way, the extent of al-Essawi’s social acceptance, if not just his total impunity, is a living reminder of the country’s surreal tilt as of late towards counterrevolution.

Reflecting on the state of things, Samah el-Saied says, “I don’t want to say the old regime is on its way back, you know, or the old system is on its way back, but you find their figures everywhere.”

Eric Knecht was a research assistant at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. Previously he was a Fulbright grantee in Egypt, and is currently enrolled in the American University in Cairo’s Center for Arabic Study Abroad.

Image: Photo: Eric Knecht