Marlon Brando, who saw his acting talent as an undesired gift, explained his method as inhabiting the character so thoroughly that all his actions were produced by its logic rather than his thinking. The intimate link between politics and theater has always been with us, Shakespeare wrote of it, the Greek dramatists never missed it, and even the ancient rulers dressed for maximum effect. We speak regularly of politics on the “public stage.” Few men in modern Egyptian history have embodied that link better than President Gamal Abdel Nasser. A protean man and a motherless child, he left a giant imprint on his nation and beyond, not because of belief in any specific philosophy or ideology, but because he lacked any and was able to inhabit the character of the hero so thoroughly that it defined his rule and his policies, leading to his rise and ultimate fall, in an arc that any dramatist would instantly recognize. Egyptians, and others beyond the Nile, were his audience, his fans, the people who loved him because of what they projected onto him, and what he reflected back on them, rather than for his political legacy, most of which was ultimately disastrous. It is not hard to imagine Nasser in a different setting, as a matinee idol in 1950s Egyptian movies, always the dashing man who solves all problems, projects masculine kindness, leaving younger women swooning and older ones grinning in maternal delight. All the while, men would hold back envy and imitate every move.

Marlon Brando, who saw his acting talent as an undesired gift, explained his method as inhabiting the character so thoroughly that all his actions were produced by its logic rather than his thinking. The intimate link between politics and theater has always been with us, Shakespeare wrote of it, the Greek dramatists never missed it, and even the ancient rulers dressed for maximum effect. We speak regularly of politics on the “public stage.” Few men in modern Egyptian history have embodied that link better than President Gamal Abdel Nasser. A protean man and a motherless child, he left a giant imprint on his nation and beyond, not because of belief in any specific philosophy or ideology, but because he lacked any and was able to inhabit the character of the hero so thoroughly that it defined his rule and his policies, leading to his rise and ultimate fall, in an arc that any dramatist would instantly recognize. Egyptians, and others beyond the Nile, were his audience, his fans, the people who loved him because of what they projected onto him, and what he reflected back on them, rather than for his political legacy, most of which was ultimately disastrous. It is not hard to imagine Nasser in a different setting, as a matinee idol in 1950s Egyptian movies, always the dashing man who solves all problems, projects masculine kindness, leaving younger women swooning and older ones grinning in maternal delight. All the while, men would hold back envy and imitate every move.

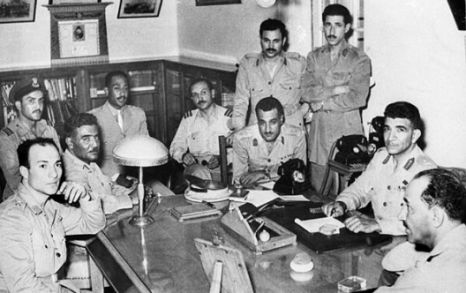

The camera is said to recognize and love a great actor. A day after the 1952 coup the Free Officers posed for a photograph. It was a stiff and public pose, with the senior officer, General Mohamed Naguib sitting behind a desk surrounded by his subordinate men. He should have been the center and focus of the camera, instead, inexplicably, the camera drifted to focus squarely on Nasser, making him the center of the photograph.

No one knew his future role, save the prescient camera. Nasser’s fate was sealed. He would act out every nuance of his role regardless of his better instincts, including those of survival. In Manshiya Square October 24 1954, on a cool night, shots rang and bullets flew toward him. He did not do the sensible thing and duck, instead he stood erect and declared that “I live for you and die for you. Nasser will not die because every man is Nasser.” This is history imitating drama. Almost exactly two years later, in the darkness of a Cairo night, his closest comrades urged him to surrender to the invading British forces and be the conscience of the nation from prison, like so many colonial leaders of the time. But that could never have been in any script that any producer would approve. He stood erect, and the improbable happened, as it would in any melodrama; the American President, Dwight Eisenhower, abandoned his erstwhile friends and allies to side with Nasser. The hero was born, again.

There was a darker side too. When Syrian wily villains approached him for a union with Egypt in early 1958 his sound judgment was to say “No.” But that was not the logic of the character, the great Arab leader. So he overruled his own good judgment and plunged in, going even as far as erasing Egypt’s eternal name, a move that sealed his political fate with many. Even worse, he authorized “limited” interference in the affairs of Arab countries as part and parcel of his role. They all rebounded badly on him, as Egyptian intelligence in those days was more farcical than most with its Clouseau-like ineptitude. Once the union with Syria failed in 1961, Nasser found himself needing to prove greatness within Egypt. He embarked on a series of economic reforms, all along socialist-realist lines, that made panoramas worthy of Diego Rivera, but crippled Egyptian growth to this very day. The great Arab leader also had to support an inept Yemeni general to the tune of 20,000 Egyptian lives. Such was the constraints of the character written for him. Nor could he back away from brinkmanship in 1967 that was to lead to a great military disaster. The most powerful argument he gave for his actions in May 1967 was a single line, Beckett-like, “I am not Anthony Eden.” The hero lives on. In the darkest hour love brings salvation. It was the genuine love of the people, as well as their bafflement, that buoyed him on June 9 1967.

Death comes once to men, but is enacted over and over again by great actors. His almost fatal heart attack in 1968 did not slow him down, but moved him to action. His greatest and most peripatetic two years were ahead of him. The great Arab hero did not die until his role dictated it. Nasser would pass away only when his Arab world would burst into the violence of “Black September.” Arab “brothers” battled each other in Jordan within earshot of their common enemy. Within hours the curtain fell on Nasser the man, but the role lives on, waiting for a new actor to take up the mantle.

Maged Atiya is an Egyptian-American physicist and businessman. He blogs at http://www.salamamoussa.com and at twitter @salamamoussa.

This article first apeared on his personal blog.