A Q&A with Dr. James Noyes, Part III of III

A Q&A with Dr. James Noyes, Part III of III

In the first part of our interview with Dr. James Noyes we discussed ISIS’ systematic program of iconoclasm as entwined with the formation of the so-called caliphate, working from Dr. Noyes’ thesis that “the destruction of religious and cultural icons has gone hand in hand with the political construction of the modern state.” In part two we turned to ISIS’ particular brand of digital-age iconoclasm—which declaims graven images while at the same time producing a never-ending stream of propagandist imagery.

In the final part of our interview we ask Dr. Noyes about the staying power of the caliphate. In cities like Raqqa, Deir Ezzor, and Mosul, ISIS is something like a colonizing force—non-native militants overturning old institutions and imposing on the local populace new systems of religious law, taxation, public services, et cetera. In the short term, guns will suffice to control the population. But in the longer term, the durability of ISIS rule depend on the group’s local acceptance. We wondered how iconoclasm might play into this process—will the destruction/replacement of local cultural heritage contribute to local acquiescence of a new puritanical order or, alternatively, hasten a process of alienation?

• In many ways, the Islamic State is an occupying force; its ranks are swelled by foreign fighters. How might iconoclasm play into the resentment of the local populace? How have transplanted iconoclastic movements fared in the past?

The Western media tends to fixate on the “Jihadi Johns” of the United Kingdom and United States, but it should be remembered that the vast majority of foreign fighters in the Islamic State are Sunni Arabs from countries like Tunisia and Saudi Arabia. This has been a factor in establishing a degree of tentative unity between the mujahideen and elements of the local population. The majority of the locals in towns like Raqqa and Mosul are also Sunni Arabs, many of whom have grievances against what they perceive to be the sectarianism of Shia-dominated governments.

It is difficult to assess the degree to which foreign fighters are integrating into the civic life of the local population. However, evidence is emerging of an Islamic State polity designed to achieve this. There are reports of a “City Charter” being circulated for Mosul, including an article on the prohibition of shirk, and signs exist of deeper infrastructural integration, particularly in Raqqa—where taxation, legal matters, and the distribution of food and energy is being administered not by foreign mujahideen but by local civilian officials who, in some cases, previously worked under the Assad government.

The Islamic State has drawn on the complex allegiances between different Sunni factions to establish itself in former Baathist strongholds like Mosul, Fallujah, and Tikrit. Since the hostilities of 2003, foreign fighters have been a regular presence in these cities. The extent to which these fighters were accepted and facilitated by locals has been a matter of debate among policymakers. In terms of iconoclasm, however, a connection has been established: for example, in the 2006 and 2007 attacks on the al-Askari mosque in Samarra, Sunni Iraqi security forces were accused of collusion with the alleged foreign culprits.

It is clear that these links between the actions of foreign fighters, the objectives of local rebels, and the everyday wishes of the local population remain highly complex. The past ten years have told us that it is impossible to predict how they will take shape in the long term. Some reports suggest that the attacks on shrines in Mosul are designed to test the water of local support, by gauging the extent to which Moslawis support the Islamic State. However, other reports are signaling that the destruction of the tomb of Jonah has marked a turning-point, with many locals furious at the perpetrators of the attack. These reports describe the emergence of local resistance forces drawn from a range of tribal and ex-Baathist factions. Time will tell whether this becomes significant or not. What we do know with certainty is that local resistance in cities like Raqqa and Mosul is met with the severest of punishments, and fear is a key factor in assessing the attitudes of the local population.

While it is difficult to assess the shifting ground of the Islamic State, past events can give us a good idea of how foreign iconoclasts fare within a local populace. These events are also relevant to our earlier discussion of the historical lineage of ISIS’ iconoclasm and Wahhabism.

A useful example is that of Bosnia and Kosovo following the Balkan wars of the 1990s. During the Bosnian War, a number of important Ottoman-era mosques were damaged or destroyed by Serb and Croat forces. Many of these mosques were rebuilt with funds channeled via Saudi Arabian charitable organizations, in addition to the building of new, Saudi-funded mosques and religious schools in Bosnian towns. This included the construction of the landmark King Fahd Mosque in Sarajevo.

These charitable organizations have been responsible for the reconstruction of over a hundred mosques in Bosnia and Kosovo, and have been accused by many experts of redesigning traditional Balkan buildings according to a “Wahhabi style”: that is, by removing the vestiges of Ottoman decoration, by whitewashing walls, and by building two minarets instead of one. In the case of Sarajevo’s Gazi Husrev Beg Mosque, the director of the Center for Islamic Architecture explained that “there were several layers of paintings, so that in the end we were in a quandary about which layer merited preservation… The biggest contribution came from a Saudi donor… Parts remain but most of the walls are now blank.”

According to Andras Riedlmayer, a Harvard-based expert on this subject, “in general, international aid agencies concerned with heritage protection have tended to shy away from projects that involve religious structures, in the mistaken belief that the reconstruction of houses of worship is a ‘sensitive issue,’ which it is best to avoid or postpone for the sake of postwar reconciliation.” He adds, “by keeping their distance from such projects, secular organizations have left the field open to sectarian sponsors, among them aid agencies from the Arab world that have their own agendas and have little interest either in the preservation of heritage or in the promotion of interreligious and intercommunal harmony in Bosnia.”

In addition to these so-called Wahhabi buildings in Bosnia and Kosovo, many foreign mujahideen settled after the war, marrying local women and worshipping in Saudi-backed mosques. Experts have noted the increase among the local Muslim population of wearing beards and the burqa—neither of which were particularly in evidence before the Balkan wars. Bosnians and Serbs refer colloquially to those Muslims as “Wahhabis”; in Raqqa and Mosul, Bosnian Wahhabis are a feature of the foreign mujahideen. This is an aspect of the historical lineage which we have been discussing.

It is evident, then, that the integration of foreign fighters and iconoclastic influences in the Balkans has depended on the extent to which they are backed by external factions. This issue has also been the topic of debate elsewhere—for example, in the case of Qatar’s role in the uprising against Muammar Gaddafi and the subsequent destruction of Sufi shrines in Libya. It is a complex issue, and I have already argued that we should be careful of overly-simplistic narratives linking Riyadh to Raqqa, particularly when we now see the Gulf states engaged in a wider military coalition against ISIS.

It is too easy to talk of direct causal connections. However, it is reasonable to talk of a climate for iconoclasm which is enabled by external support. This enabling climate determines whether or not foreign fighters will be able to settle, in the long term, in territories like the “Islamic State” in the same way that they have settled in the former Yugoslavia. In the case of Kosovo and Libya, the West’s focus on removing Milosevic and Gaddafi enabled certain iconoclastic influences to take shape out of view. Today, while an international coalition begins to attack the Islamic State, it lacks a coherent strategy to counter rampant sectarianism or restore local governance across this geography. This is the kind of uncertain hinterland in which iconoclasts operate. Both local Sunnis and foreign mujahideen are aware of this, and the nature of their relationship will be shaped by the enabling climate.

Since the Soviet war in Afghanistan, a common view has been that the “cookie trail” for foreign mujahideen leads back to the Gulf. Today, the West must decide whether they are comfortable with the cookie trail leading back to them too, particularly when it involves the destruction of religious minorities. Gulf support for the American-led campaign against ISIS has been celebrated as a first step towards answering this, but time will tell whether public support from Gulf governments will equate to a reduction in private donations to militants, or whether future Gulf-endowed mosque-building and cultural restoration projects in northern Iraq and Syria will take a different path from what we have seen in Libya, Kosovo, and Bosnia.

Past coalitions were prepared to turn a blind eye to the construction of “Wahhabi” mosques and the destruction of Orthodox churches in the Balkans, because their overriding goal was to topple Milosevic. The question today is how much iconoclasm the West and its allies are willing to tolerate in their long-term goal of stabilizing the Levant and Iraq. This is where we enter the sphere of geopolitics, and a daunting one at that: working out who stands with whom in the balancing act of autocrats and iconoclasts.

Read Part I of III here: Iconoclasm and the Islamic State: Razing Shrines to Draw New Borders

Read Part II of III here: Iconoclasm & the Islamic State: Image-Maker vs. Image-Breaker

Matthew Hall is an assistant director with the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

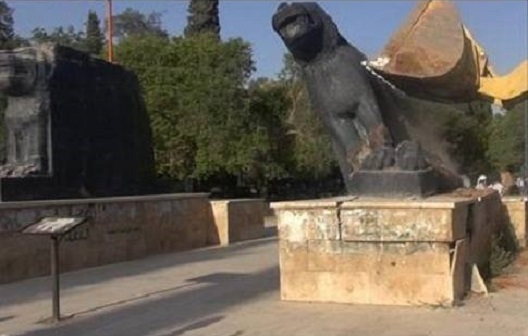

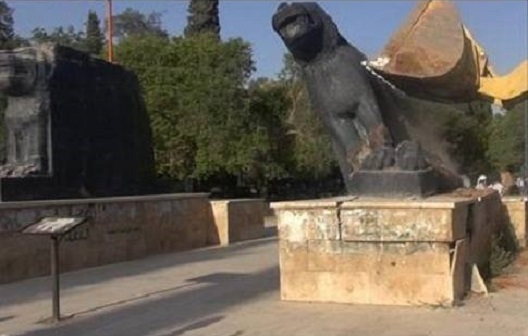

Image: An 8th century BC portal lion from the Neo-Assyrian city of Hadatu is destroyed by a bulldozer as ISIS militants seize control of Raqqa, Syria in 2013. The basalt lions, which guarded the entrance to the ancient temple complex, were not incidental to Hadatu; the Turkish name for the city, Arslan Taş, means “Stone Lion.” (Courtesy Gates of Nineveh blog / Association for the Protection of Syrian Archaeology, APSA)