The month of April marked the tenth anniversary of the fall of Baghdad, the third provincial election of the post-Saddam era—the country’s first without the presence of US troops—and seven years since a relatively unknown Nouri al-Maliki emerged as the prime minister of Iraq. Nevertheless, after a period of relatively low violence and another election added to Iraq’s nascent democratic experiment, the country is entering the most unstable period since it plunged into a sectarian civil war (2005-07) during the height of the insurgency.

Today, Iraqi politics may be on the verge of relapsing into a period of sectarian violence, whereby a new political framework would be required to reset communal relations.

Power and sovereignty disputes between the Shia-dominated government in Baghdad and the Sunni-dominated provinces of central and northern Iraq have caused tensions to simmer for years. At the center of most political disputes is the gradual consolidation of power by the prime minister—a recipe for disaster in a country that relies on power-sharing agreements. Last December, tens of thousands of Sunnis came out in peaceful demonstrations, protesting the Maliki government’s recent wave of political intimidation and marginalization toward the Sunni political class. After months of widespread protests, the prime minister could not satisfy the unrealistic demands of an increasingly overconfident Sunni movement, inevitably leading to deadly clashes. Beginning last week in the northern Iraqi city of Hawija, clashes have now killed hundreds of Iraqis, prompting retaliatory attacks and compounding the conditions for a wider conflict.

Today, there is no foreseeable end or limitation to how far the situation can escalate toward renewed civil war. The usual course of Iraqi crises has been cyclical: an incident occurs; disputes ensue while rhetoric escalates; a climax is eventually reached; but the trigger is never ultimately pulled. The crisis gradually dissipates with disputes still unresolved. But that does not appear to be happening this time.

The critical level of stability provided by the psychological effect of the US military presence is gone, and more concerning, war fatigue is showing real signs of wearing off. These features were Iraq’s coolants, producing a pacifying effect for the country’s turbulent politics and keeping crises cyclical rather than escalating them. But when US troops withdrew from Iraq in December 2011, it was apparent that a dangerous and new phase of politics immediately followed, as the prime minister sought to arrest a sitting vice president while attempting to sack his deputy prime minister and finance minster—all prominent members of the Sunni community and key partners in Iraq’s power-sharing government.

Iraq seems to be experiencing a system overload. Its fragile and nascent politics is not built to sustain the current levels of endogenous and exogenous pressure. Not only have tensions reached new highs due to the domestic build up of unresolved disputes, but are aggravated by the extraordinary and unstable dynamics in the region in the wake of the Arab spring. The ascendency of Sunni Islamists across the Middle East and a regional proxy war playing out in neighboring Syria have hardened sectarian structures, intensifying Shia fears and Sunni hubris in Iraq, a dangerous mixture that has shaped the reckless miscalculations of political actors on both sides.

The prime minister perceives the Sunni protest movement as an extension of the revolution inside Syria. The Sunnification of a neighboring state has spurred fears among Shia leaders in Baghdad about their geostrategic encirclement, the dangerous emboldenment of Sunni rivals in Iraq, and the resurgence of insurgent groups finding an increasingly favorable environment in Iraq’s Sunni heartland. Maliki seems to believe rumors about the alleged formation of a “Free Iraqi Army” and its cooperation with the Free Syrian Army, whose flags can be seen raised in Iraqi protests. For Baghdad, the downfall of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad at the hands of Sunni revolutionaries will usher in a wave of threats challenging the preservation of the Maliki regime.

It is not unusual for post-conflict states to relapse and return to civil war, especially when power-sharing agreements collapse or are no longer viable for the parties involved. It is too soon to tell if the latest wave of deadly clashes will take Iraq through another cycle of sectarian conflict; the worst-case scenario is two adjacent civil wars in Syria and Iraq occurring simultaneously along sectarian fault lines, an outcome the United States has a strong interest in preventing.

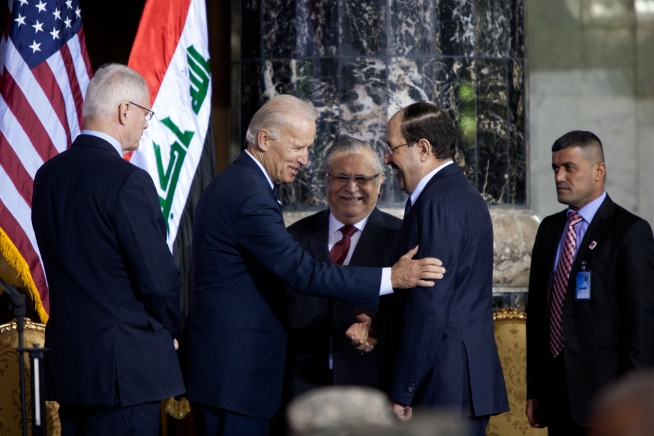

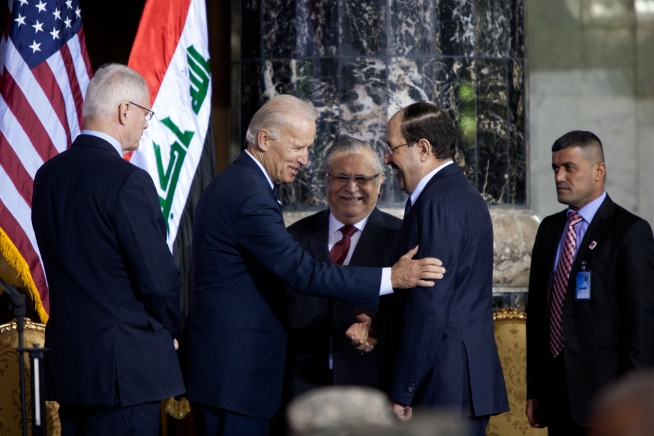

Although its influence has diminished over the years, the United States remains the only outside power that can reach all sides. The Turks and Iranians may be strong at the local level, but are limited on the national stage and bounded to their sectarian spheres of influence. Without Kurdish political leader and President of Iraq Jalal Talabani (who is recovering from a stroke he suffered in December) on the political scene, the Kurds are not positioned to play a mediating role between Shia and Sunnis, and the United States will not be able to rely on any Iraqi to effectively and quickly facilitate the necessary diplomatic efforts.

Rather than publicly deplore the deadly clashes and risk appearing to choose sides, the United States should create an off ramp for the escalatory spiral now driving the crisis to a point of no return. Washington should quickly signal its willingness to play the leading role in bringing the parties together for talks under its auspices. There are no guarantees, of course, but the proposal may provide the required face-saving mechanism for Iraqi leaders to disengage from the current destructive path. Any strong attempt will require private discussions with all Iraqi sides and from the highest levels of the US government (especially the president), and a subsequent public announcement.

The United States should press Iraq’s leaders to dial down their rhetoric and (publicly and privately) urge calm among their constituencies. Language should be coupled with action on the ground. Maliki needs to disengage his security forces from the areas of conflict while Sunni leaders must move to demobilize their opposition movement. If there are indications of deescalation, the United States should immediately revive a national dialogue process that can help manage the sectarian tensions. This painstaking engagement will be a necessity as the civil war in Syria progresses.

Any diplomatic effort should keep in mind that Iraqi politics favors incrementalism, not grand bargains. A political deal is not required to relieve pressure in the short term, and negotiations in times of crisis should not seek to resolve the country’s underlying problems, which will require decades of good governance and national reconciliation. Past efforts at dialogue failed to materialize because they were overwhelmed by the depth and scope of political demands.

In addition, Washington will need the cooperation of its regional Sunni allies working toward the same end, especially Ankara, which has not played a positive role in Iraq since it began interfering in its domestic politics and choosing sides in the previous election cycle (2009-10). The US withdrawal compelled Turkey to abandon its foreign policy of nonalignment to one of filling the void and balancing out Iran. But Turkish leaders must understand that Iran is best checked with the emergence of cross-sectarian politics in Iraq, not its own attempts at balance-of-power politics. Thus far Turkish behavior has been counterproductive to this end, only reinforcing the sectarian order, keeping Iraq divided, the Shias united, and Iranian influence at its optimal level.

Unfortunately, voter turnout in the 2013 provincial elections was dramatically lower than in 2009, the last time Iraqis casted their ballot in local elections. It is well known that many Iraqis have lost confidence in elections as a credible venue for reform and to express the will of the people. Although gaining confidence in the electoral process is a long-term goal for the Iraqi political class, the immediate challenge for the United States is to help the Iraqis complete this electoral cycle, including local elections in Anbar and Ninawa provinces and national elections next year.

The United States has always struggled to get Iraqis to cooperate, regardless of the size of the US military presence. American influence has declined over the course of the years, not because of the drawdown (and ultimate withdrawal) of troops on the ground, but primarily due to the rise of Iraqi politics and the formation of domestic interests and constituencies. The formation of political interests and the costs associated with acting against those interests effectively limited the extent Iraqi politicians were willing to extend what was the US occupation of their country. Nevertheless, the United States’ failure to secure a follow-on agreement with the Iraqi government, which would have extended the US troop presence after 2011, altered and widened the boundaries of Iraqi politics to a point that its fragile system was not prepared to shoulder and manage.

Ramzy Mardini is an external contributor to the Atlantic Council. He is an adjunct fellow at the Beirut-based Iraq Institute for Strategic Studies. Photo Credit.