Today, Iraqis head to the polls to take part in the country’s parliamentary elections, the first since the United States completely withdrew its military forces in December 2011. While elections will only initiate the game in shaping the next government in Baghdad, it is the post-election gamesmanship, which involves an interplay of internal and external dynamics, that determines who will govern Iraq.

Today, Iraqis head to the polls to take part in the country’s parliamentary elections, the first since the United States completely withdrew its military forces in December 2011. While elections will only initiate the game in shaping the next government in Baghdad, it is the post-election gamesmanship, which involves an interplay of internal and external dynamics, that determines who will govern Iraq.

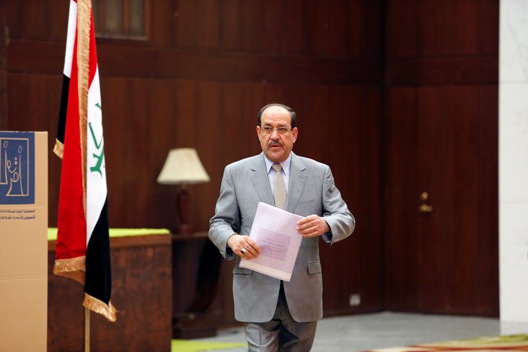

After the votes are counted, all eyes will be on Nouri al-Maliki, the current prime minister, who is running to secure his third consecutive term. Since coming to power in 2006, he has consolidated and centralized power, marginalized opponents, purified his regime of non-loyalists, and deepened his entrenchment in the country’s security apparatus. Some observers contend that should Maliki gain a third term, he will be unlikely to leave power for good, making the 2014 electoral cycle the most determinative to Iraq’s future since the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003.

The single most important dynamic that will drive the post-election gamesmanship to form the next government will be the reactionary behavior of Iraq’s political parties toward Maliki. In other words, will the other parties choose to cooperate with one another in balancing against him, or chose to be opportunistic and bandwagon with him?

The last cycle of national elections took place in March 2010, whereby no electoral bloc came close to gaining a majority of the seats, thus ensuring a nine-month political deadlock. The 2014 national election will not yield an outright winner either, and Iraqis are anticipating another lengthy government formation crisis. Within the 325-seat Council of Representatives, a majority coalition of 163-parliamentarians is required to form the next government. While Maliki’s State of Law bloc will fall well below reaching that critical mass after the votes are counted, it remains unclear whether or not Maliki will be able to form the necessary alliances to secure the premiership, retain his post, and form his government.

In 2010, the government formation crisis ended with the formation of a comprehensive US-backed power-sharing government, in which all electoral blocs took part in the Council of Ministers, the executive cabinet. But given the unanimous dissatisfaction with that governmental framework, this year, it is more likely a majoritarian government will be formed.

The prime minister is likely to win more seats than any other political opponent. Unlike all of his opponents, who are running on their own separate party lists, Maliki is heading a coalition of parties. In the 2010 elections, Maliki’s State of Law bloc, which remains nearly identical going into the 2014 elections, won eighty-nine seats. If he can perform at the same level this time around, he will be in fairly good shape to retain the premiership, but his hold on the post is not inevitable. There remains deep resistance toward a third Maliki term, coming from Shia and Sunni Arabs, as well as Kurds.

Maliki appears more vulnerable today than in the run up to the 2010 general election, when security had improved dramatically in Iraq and he won nine out of the fourteen provinces that participated in the provincial elections in 2009. During the last electoral cycle, Maliki retained his position after gaining the support of two kingmakers: the Kurds and the Sadrists. Both held reservations about Maliki, but eventually backed him for a second term after cutting deals with him behind closed doors. Today, Maliki’s reputation for not reciprocating after getting what he wants (i.e. the premiership) has tainted his credibility to cut deals and share in Iraq’s spoils. This perception has further limited his options for future coalition partners, most importantly among the country’s electoral kingmakers.

Apart from the domestic dynamics, there is a regional component of the government formation process, which has the potential to determine how the next government is shaped. Politics in Iraq is not a game played by Iraqis alone, but rather represents a subset of regional politics. Indeed, the interests and machinations behind every electoral cycle is a competition between various players, including the United States, Iran, Syria, Turkey, Lebanese factions, and members of the Gulf Cooperation Council, particularly Saudi Arabia.

While Washington constantly touts its influence, it remains on the decline due to the fact that—unlike other external actors—the United States is not a patron of Iraq’s patronage politics. The most influential player is Iran, whose core interests rest on the unity of the Shia political class. As long as the Shia Arabs who represent an ethnic majority in Iraq remain united, Iran’s ability to project political influence is secured. If they are divided, whereby the governing coalition is cross-sectarian, Iran’s influence becomes diluted.

In the 2005 general elections, Iran formed and backed the ruling pan-Shia coalition, the United Iraqi Alliance, which represented the purist form of Shia unity and dominated Iraqi politics. But during the 2010 elections, the Shia political class began with an initial split between two major camps, with Maliki on one side, and the Shia parties of religious clerics Muqtada al-Sadr and Ammar al-Hakim on the other. With Iranian pressure, the two rival blocs later merged, but nevertheless, it had nearly cost Maliki the premiership. This year, rivalries and divisions within the Shia community appear as intensified as ever, with each political party running on its own (except for Maliki’s State of Law coalition).

The deep resistance towards a Maliki third term will make Iran’s goal of maintaining Shia unity far more complicated than at any time in post-Saddam Iraq. Due to the level of disunity and resistance against the status quo, other Shi’a personalities with strong Iranian sponsorship could potentially emerge as possible premier contenders, especially if Maliki is unable to attain a large enough coalition to support his third term.

Due to the depth and scope of Maliki’s entrenchment within Iraq’s security apparatus over the course of the last eight years, Maliki’s political rivals are highly unlikely to oust him from power without him voluntarily stepping aside. Tehran is unlikely to easily flip against Maliki, given the concern that change in Baghdad, regardless of who comes into power, could symbolically undermine the status quo in Damascus. In the end, Maliki’s ability to secure a third term will depend on what Iran ultimately decides—and if he’s able to cut the necessary deals with potential coalition partners.

Ramzy Mardini is a nonresident fellow at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

Image: Iraq's Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki walks to cast his ballot during parliamentary election in Baghdad April 30, 2014. Iraqis head to the polls on Wednesday in their first national election since U.S. forces withdrew from Iraq in 2011 as Prime Minister Nuri Maliki seeks a third term amid rising violence. (Photo: REUTERS/Ahmed Jadallah)