The Houthis and Saudis have been talking in Riyadh for months, not only recently as suggested by reports last week. But formal peace talks failed as the kingdom insisted on the implementation of United Nations Security Council resolution 2216, which calls for a full surrender of the Houthis. What led to the breakthrough of the Saudi-Houthi prisoner swap and pause the fighting on the Saudi border?

The Houthis and Saudis have been talking in Riyadh for months, not only recently as suggested by reports last week. But formal peace talks failed as the kingdom insisted on the implementation of United Nations Security Council resolution 2216, which calls for a full surrender of the Houthis. What led to the breakthrough of the Saudi-Houthi prisoner swap and pause the fighting on the Saudi border?

One issue may be economic. Following on the heels of the news of progress in Saudi-Houthi talks came the announcement that Saudi Arabia was seeking its first loan in over a decade, to the tune of $6-8 billion. The kingdom’s budget deficit exceeded $100 billion last year, and while the kingdom is not in financial trouble the loan request illustrates that its resources are not limitless.

A second issue may be the flood of pressure and criticism of the kingdom, from its bombing of civilian sites in Yemen to its abysmal human rights record and executions of peaceful political dissenters at home. The war in Yemen has created a massive humanitarian crisis: about 85 percent of Yemenis desperately need water, food, medicine, and fuel—21.2 million people in total, including 9.9 million children. Reports that Yemen may be on the verge of a famine have been circulating for at least six months.

These problems are not new and numerous groups have sought to address them. Only last fall, a Dutch-led effort to form a human rights mission to Yemen was stifled by the kingdom, seemingly with the support of the United States. A January United Nations report that asserted that the Saudi bombing campaign had resulted in widespread and systematic attacks on civilian targets brought little response. The United Nations also has been struggling to conduct an Emergency Food and Nutrition Assessment throughout the country, but Saudi refusal to assist in that effort brought little international response.

Over the past month, however, criticism of the humanitarian crisis in Yemen, possible war crimes by Saudi Arabia and the kingdom’s domestic repression have come from more formal political channels, sometimes at the highest levels. The UN Security Council recently opened debates around a resolution to address the Yemeni humanitarian crisis, despite showing little interest in the topic just a few months ago. Although still under consideration, the statement could insist on the protection of hospitals and the delivery of humanitarian aid, which would need to be facilitated by all parties. If such a resolution were to pass, it would direct significant pressure toward Saudi Arabia, marking a sharp departure from UNSC 2216. The kingdom is clearly troubled by Security Council interest in Yemen. The Saudi ambassador to the UN stated that there was simply no need for such a resolution, as the kingdom was only carrying out a military campaign to restore the legitimate government and not targeting civilian sites.

Other nations are not persuaded. In the United Kingdom, MPs launched an investigation to determine if UK weapons sold to Saudi Arabia had been used in war crimes in Yemen, which would be a violation of British export controls. The UK government has strongly supported the creation of a UN committee that would examine incidents in which civilian spaces are bombed.

Organized pressure from citizens and civil society groups in Europe succeeded in getting the European Parliament to call for an EU-wide arms embargo on Saudi Arabia, citing the immediate need to fully investigate all violations of international humanitarian law. The resolution is not binding, but more initiatives would make it difficult for nations to sell arms to Saudi Arabia without attracting negative attention.

In the United States, Sen. Chris Murphy of the Senate Arms Service Committee broke the silence on the US-Saudi alliance and raised the issue of ending military support for the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen, citing mounting evidence of civilian deaths. He argued that US support for the Saudi aerial campaign directly contributed to the humanitarian crisis and facilitated the conditions for the expansion of Islamist extremism.

Perhaps most significantly, President Barak Obama recently voiced his frustrations with having to treat the kingdom as an ally for geostrategic reasons. He emphasized Saudi’s well-known export of Wahhabi extremism and its repression of “half its population.” The timing of Obama’s comments—during his final year in office, but before his tenure has ended—puts significant pressure on Saudi Arabia even as Washington continues its support for the kingdom. The conventional assumption has been that geostrategic logics will always trump calls for ending those long-standing alliances in the region because stability—even if that means allying with unsavory regimes—is preferable to the alternative.

But with the nightmare scenario of civil wars, collapsing states, and rising extremism now a reality, Saudi Arabia is coming under fire for its role in some of those conflicts. Although King Salman and particularly Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman are intent on Saudi Arabia playing an active military role in the region, attention to the long-term costs of the war in Yemen and repression inside the kingdom may create the logic for Saudi Arabia to bring the war to a close in the next months, even if that means giving the Houthis a seat at the table in determining Yemen’s future.

Jillian Schwedler is a Nonresident Senior Fellow for the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

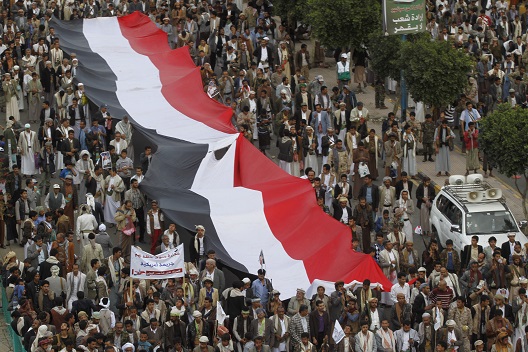

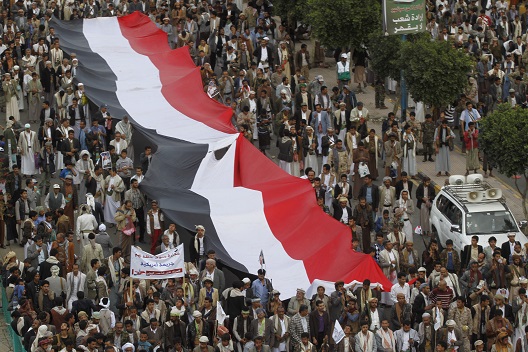

Image: Followers of the Houthi movement hold a giant Yemeni flag during a rally against U.S. support to Saudi-led air strikes, in Yemen's capital Sanaa, March 1, 2016. (Reuters)