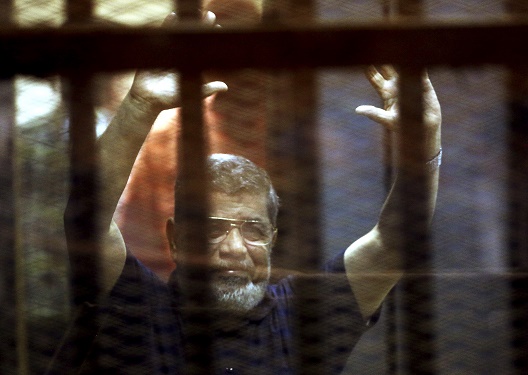

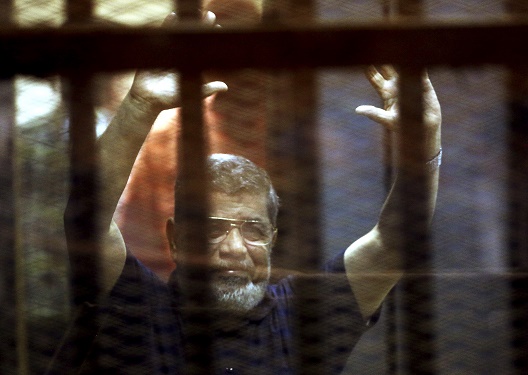

In the blistering heat of a Cairo courtroom in May, a resolute looking Mohammed Morsi listened as the judge announced a death sentence for charges of corruption and torture against the ousted president, which allegedly took place during his one year in power in 2012. Alongside Morsi, hundreds of his fellow Brotherhood members, many senior leaders within the organization were also assigned death sentences or long prison terms. A court also upheld a life sentence today against the ousted president in a case where he was also accused of conspiring with foreign powers—although how long that sentence will hold will depend on how successfully Morsi can prolong his life. After consultation with Grand Mufti Shawki Allam’s advisory opinion on the death sentence, the same court today confirmed the death sentence against Morsi. With this verdict, will Egypt’s military rulers consign the world’s oldest Islamist organization to the dustbin of history?

In the blistering heat of a Cairo courtroom in May, a resolute looking Mohammed Morsi listened as the judge announced a death sentence for charges of corruption and torture against the ousted president, which allegedly took place during his one year in power in 2012. Alongside Morsi, hundreds of his fellow Brotherhood members, many senior leaders within the organization were also assigned death sentences or long prison terms. A court also upheld a life sentence today against the ousted president in a case where he was also accused of conspiring with foreign powers—although how long that sentence will hold will depend on how successfully Morsi can prolong his life. After consultation with Grand Mufti Shawki Allam’s advisory opinion on the death sentence, the same court today confirmed the death sentence against Morsi. With this verdict, will Egypt’s military rulers consign the world’s oldest Islamist organization to the dustbin of history?

Morsi’s fate could mean the end of the Muslim Brotherhood, but it is more likely that the organization will be pushed into the political wilderness for the foreseeable future. The organization has faced a severe crackdown since July 2013 when General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi took power from Egypt’s first democratically elected president, following a popular uprising against Muslim Brotherhood rule. The subsequent clampdown on both the Brotherhood and leftist opposition groups has been one of the most brutal in Egyptian history. Over 800 Muslim Brotherhood supporters were killed during protests against Morsi’s ouster in Rabaa al-Adawiya Square. This level state brutality even exceeded the 500 death toll in Tiananmen Square in 1989.

The crisis has been compounded by serious divisions within the Brotherhood. Questions among Islamists arise over how the organization should respond to state repression and how to regain the support of the Egyptian people, many of whom support Sisi’s heavy-handedness following Morsi’s removal. Sisi was elected in May 2014 with 97 percent of the vote, marking a desire among many Egyptians to return to stability after four years of chaos. In a 2014 survey by the Pew Centre, some 43 percent of Egyptians think that a leader with a strong hand is the best way to deal with Egypt’s myriad challenges. It seems as though a return to strongman politics in Egypt is here to stay.

Meanwhile, the Muslim Brotherhood appears to be in internal disarray. Younger leaders previously in mid-ranking positions with little influence in the Brotherhood’s Guidance Bureau—the former apex of command authority within the organization—have now been fast tracked into leadership roles. A social movement that is part political party, part national charity, the Muslim Brotherhood has always been an organization that is difficult to characterize. The Brotherhood has always had to deal with internal dissenters—whether it was Sayyid Qutb’s formative jihadist group Organization 1965, or Ayman al-Zawahiri’s Al-Jihad, who helped organize the televised assassination of President Anwar Sadat in 1981, or the Islamist insurgency of the 1990s. The Brotherhood has always been at the heart of Egypt’s Gordian Knot, where the role of Islam and state power remains unresolved.

Decentralized and severely damaged by mass arrests and exiled leaders, the Brotherhood now makes decisions without authorization from the Guidance Bureau, with newly elected youth committees managing the banned organization. Recent reports suggest that the older generation, many of whom are now based in Istanbul (led by the Brotherhood’s Secretary-General Mahmoud Hussein), are wary of the young wing’s violent rhetoric against the Sisi regime. Hussein and older hardline leaders such as Mahmoud Ezzat are eager to maintain a reformist approach to the system, which the group adopted for during the Mubarak era. However, the past week, Mohamed Montasser, the group’s Cairo-based media spokesman, stated on the Ikhwan Facebook page that the group would aim to “restore legitimacy, exact retribution for the martyrs, and rebuild Egyptian society on a sound and civilized basis.” Many younger leaders feel that Mubarak-era strategies are useless in the post-2013 environment. Without a strong central leadership, mixed messages will reinforce the idea that the Brotherhood will remain politically insignificant, undercut by a lack of finances and inexperienced leadership.

Still, the Islamist group should not be written off. The organization has shown resilience in the face of state violence under successive military leaders, from Nasser to Mubarak. For some within the organization, in particular the youth, the answer to the Brotherhood’s current difficulties lies in diverging from the past. Some members want to realign themselves with the April 6 Youth Movement, a youth revolutionary group that was instrumental in the 2011 uprising. This is not entirely implausible, given the largely informal links the Brotherhood previously forged with the 2005 Anti-War Coalition, the 2007 Kefaya protests, and leftists and secular protesters in 2011. If the Brotherhood youth can break away from single-mindedness and genuinely establish lasting alliance with April 6 and other groups, this youth alliance could be a persistent plague on Sisi’s military regime. These groups have shared goals: an independent judiciary, free and fair elections, an end to Emergency Laws, and an open press free of state intimidation. These issues link all opposition groups, whether Islamist or secular.

However, distrust of the Brotherhood after their one year in power is deeply rooted. During Morsi’s year in power, the government oversaw the arrest of activists, cracked down on high-profile media voices (Egypt’s very own Jon Stewart, Bassem Youssef was arrested in a publicized manner following satirical TV sketches mocking Morsi), and refused to give the revolutionary youth parties a voice in the post-Mubarak government. Nevertheless, the Egyptian populace may begin to view the Brotherhood in a more sympathetic light, given Sisi’s crackdown on opposition and the indefinite postponement of parliamentary elections. Still, short-term violence is likely to escalate. Sinai has been practically lost to an Egyptian affiliate of Islamic State (ISIS or ISIL) and the region has witnessed a visible upsurge in violence against the police. Meanwhile, the United States and European Union appear unwilling to question Sisi’s authoritarianism, instead trading acquiescence for Sisi’s alliance in the name of fighting extremism. Violence is also ascending across the Arabian Peninsula, which is likely to encourage jihadists in Egypt.

If the West has learned one thing from the last decade in the Middle East, it should be that when state authoritarianism persists, it encourages recruitment among extremist Islamist groups. While Morsi and the Brotherhood are being pushed aside, these extremists will grab the mantle of the Islamist cause, taking it to darker depths far beyond Egypt. In the face of unrelenting confrontation by both state and non-state actors and growing internal division within the Brotherhood, Egypt will likely face an ever-escalating cycle of violence.

Dr. Gillian Kennedy is a Visiting Research Fellow for the Institute of Middle Eastern Studies (IMES) at King’s College London.

Image: Former Egyptian President Mohamed Mursi reacts behind bars with other Muslim Brotherhood members at a court in the outskirts of Cairo, Egypt May 16, 2015. (Reuters)