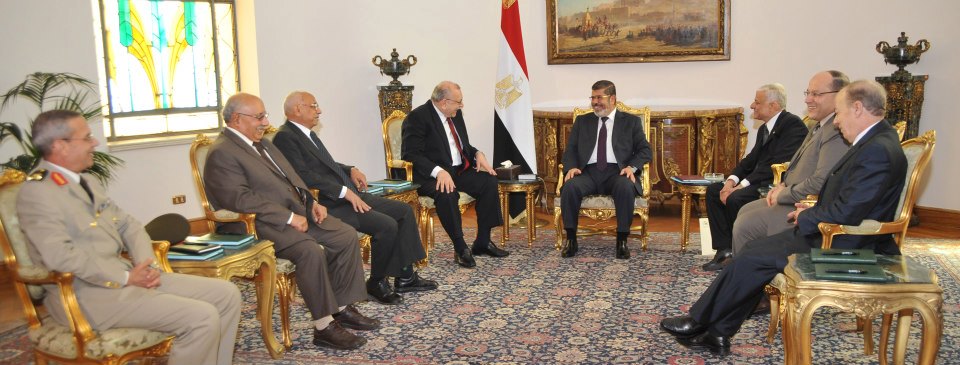

With a volatile and tumultuous environment surrounding the relationship between the judicial authority and the ruling regime, a Supreme Judicial Council (SJC) delegation visited President Mohammed Morsi on April 28. This visit came amid tension caused by the introduction of amendments to the Judicial Authority Law (JAL). During the visit, they presented a proposal to the president to hold a “Second Justice Conference” to discuss the problems of the Egyptian judicial system and how to overcome them. The proposal was met with approval from the president and preparations are currently underway for the conference in the coming weeks. So what exactly is this Justice Conference? What happened in the "first" Justice Conference? What is the reasoning behind holding this conference now? Finally, does this conference aim to do away with the tension between the judicial [authority] and the regime, as well as to reform the judicial authority in Egypt as needed?

The Justice Conference is a large forum, attended by all parties involved in judicial affairs, where they discuss challenges facing the judicial system and propose solutions and potential remedies. The inaugural Justice Conference took place in 1986, attended by former president Hosni Mubarak, where several research papers and significant proposals were presented. In them, they called for the independence of the judiciary and an end to the executive authority’s control over it. Other proposals dealt with increasing the efficiency of the judiciary. The first Judicial Conference ended with the issuance of specific recommendations that could be carried out, encompassing nearly all aspects of judicial reform. The recommendations covered seven topics involving legislation, litigation procedures, the judicial system, judicial affairs, and of course support for judicial independence. The recommendations were issued in April of 1986, with the request for a second Justice Conference to be held in March 1987. The second conference was never held.

It is unclear what prompted the SJC to propose a second Justice Conference at a time like this. It may be an attempt to find a way out of the crisis brought about by the proposed amendments to the Judicial Authority Law. What matters, however, is whether the conference is held at the appropriate time. I, along with many, if not most judges, believe that this conference is being called for at the wrong time and in the wrong place. President Mohamed Morsi suggested that the conference, along with all preliminary and preparatory meetings, to be held at the presidential palace. This suggests that the whole affair will take place under the auspices of the presidency, despite the fact that it’s a purely judicial matter. Instead, the conference should be taking place solely as a judicial initiative, and under judicial administration, in order to uphold the image of a judicial authority that is independent of the executive authority. In addition, there is a feeling of dissatisfaction among a large section of judges and politicians due to the fact that the call for this conference comes as a directive from the president, the very person who attacked the judiciary on a number of occasions in his less than ten months in power.

The reason the timing for a second Justice Conference is also inappropriate is clear: the extreme political polarization that dominates Egypt’s political and social space. This has hindered attempts at reform and change, no matter which side it comes from, due to a pervading sense of doubt when it comes to each party’s intentions. Additionally, the tension and suspicion prevailing in relations between the judiciary and the ruling authority guarantee that no real attempts at reform will succeed. The way out of this, before discussing a Justice Conference or any other steps for reform, is through serious work on all sides, whether from the regime or the opposition, to mitigate the tension and polarization in the country by carrying out trust building measures. The goal of this is to establish at least some common ground for all to work from.

Most of the decisions and recommendations that will be issued from this Justice Conference, if it is held, will need to be written out in legislation and laws from the legislative body charged with their implementation. This brings us to another example of why the timing for the conference is inappropriate. The Shura Council — that currently deals with legislation — is not able to issue these sorts of laws that have to do with judicial authority.

On the one hand, I believe the Egyptian Shura Council carries out all legislative authority in a way that is unlawful. The Shura Council still lacks legitimacy as we are at the threshold of a new session on June 2 when the Constitutional Court will look into a case filed against the body’s legitimacy.

On the other hand, even when assuming that the Shura Council is fully entitled to legislate, there is yet another problem. Certain laws gain special importance because of their connection to the constitution and serve to implement its provisions. These are called “laws complementary to the constitution”, and they take place in special discussions in parliament. The entire bicameral parliament – the Shura Council and yet-to-be elected House of Representatives – are charged with discussing these laws, the most important of which is the JAL. On this basis, Egypt’s Judges Club has filed a claim against the president of the republic and the speaker of the Shura Council, requesting to ban the Shura Council from discussing and issuing the JAL. This claim is now being deliberated by the Administrative Judicial Court.

Holding the Justice Conference in the coming weeks will not mitigate the state of tension and political polarization, and in this context is not the proper way to achieve the desired judicial reform. The recommendations that came out of the first Justice Conference—27 years ago—were never implemented, particularly those that were important and effective. This is in spite of the fact that the recommendations addressed problematic areas in the Egyptian judicial system to a large degree, and proposed ways to reform these issues. What can be concluded here is that the path is clear for whomever wants reform, even though the most essential element of reform is still missing: political will.

Yussef Auf has been a judge in Egypt since 2007. He is currently a non-resident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East in Washington DC where he focuses in his research on Constitutional issues, elections and judicial matters. He can be reached at yussufauf@hotmail.com.

Photo: Egypt Presidency

Image: Morsi%20Judges%20Egy%20Presidency.jpg