Fears of electoral violations tend to revolve around ballot fraud and bribery, but the biggest threat to the integrity of Egypt’s upcoming presidential race may lie on the campaign trail, far away from polling stations. The leading presidential candidates are believed to be exceeding the LE 10 million limit on campaign spending by a significant threshold, in addition to violating the ban on advertising prior to the start of the official campaign period on April 30. On May 14, the Supreme Presidential Election Commission (SPEC) announced that it will take legal action against violators, citing strong suspicions that some candidates had already succeeded the LE 10 million limit well before the close of the campaign period.

Egypt’s electoral law imposes strict regulations on the amount and origin of campaign donations:

- Candidates can spend a maximum of LE 10 million on campaigning in the first round of elections and an additional LE 2 million for the runoff round.

- Campaigns are strictly forbidden from accepting foreign donations

- No individual can donate more than LE 200,000 to any campaign.

- Violators can incur penalties of up to LE 100,000 in fines and up to one year in prison

- Candidates are barred from campaigning at places of worship.

But the regulatory apparatus for monitoring compliance with these regulations is largely spineless, given the lack of transparency in campaign donations and the difficulty of proving and punishing violations:

- The Supreme Presidential Election Commission (SPEC) requires presidential candidates to open special bank accounts associated with their campaigns in one of three state-owned banks.

- The Central Auditing Agency is responsible for overseeing campaign spending.

- Candidates are required to report all donations to the SPEC and specify how the funds are spent. Within 15 days of the announcement of election results, candidates must provide the SPEC with a detailed statement documenting campaign expenditures.

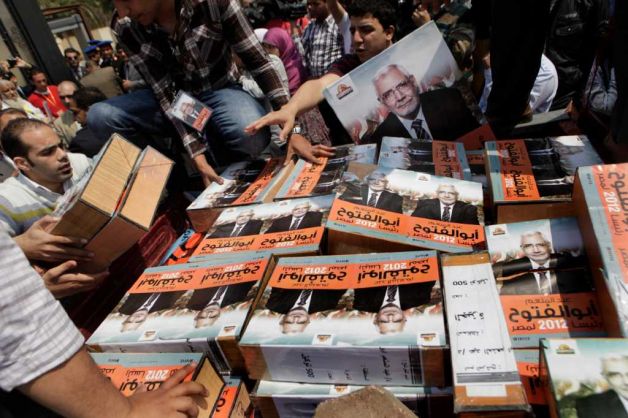

Election authorities had little success enforcing campaign spending limits in the parliamentary elections – in which some MPs spent as much as LE 10 million on campaigns that were capped at LE 500,000 – and regulating the presidential race will be just as difficult. The two leading candidates, Amr Moussa and Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh, claim to have spent only LE 3 million and LE 7 million respectively. But these figures don’t compute with the exorbitant cost of advertising (Aboul Fotouh’s television ads alone cost LE 3 million to produce). Advertising executive Tarek Nour has estimated that the most basic campaign for a serious presidential candidate would cost at least ten times the current cap. Amr Moussa himself recommended that spending limits be raised due to the rising cost of advertising during Egypt’s first-ever televised presidential debate on May 10.

The candidates have been quick to allege spending violations by rivals while insisting their own campaign operations are compliant. On March 22, Aboul Fotouh claimed that LE 50 million in foreign funds had recently been funneled into Egypt to support various presidential candidates, saying he fears the money will be used to bribe voters. Now that Aboul Fotouh has been endorsed by Egypt’s powerful Salafis – believed to have illegally channeled funding from the Gulf countries into Salafi parliamentary campaigns – his own campaign is likely to become an object of suspicion and scrutiny.

At the end of March, the Justice Ministry announced it is investigating a claim that the Ansar al-Sunna al-Muhammadeyya, a Salafi religious association, received LE232 million in funding from outside of Egypt, some of which was earmarked to support an unspecified presidential campaign – which could be none other than Aboul Fotouh’s.

The Muslim Brotherhood has also been suspected of using foreign funding in violation of electoral regulations. During the parliamentary elections, prominent liberal Naguib Sawiris had accused the Muslim Brotherhood of accepting LE 100 million from Qatar, and he now claims that the Brotherhood is using Qatari funds to support Mohamed Morsi’s presidential campaign.

Another challenge in regulating campaign spending is the growth of independent fundraising campaigns launched by supporters of the presidential candidates outside the official campaign apparatus.

Since these “unauthorized” fundraising activities are not subject to oversight by the official presidential campaigns, they are nearly impossible to track or regulate. While Aboul Fotouh has repeatedly insisted that he is an independent candidate not beholden to any particular donor, this has not stopped him from capitalizing on the outreach efforts of supporters who are campaigning unofficially on his behalf. Aboul Fotouh has already benefited from at least one documented case, in which volunteers organized independently to create a volunteer database and campaign separate from the official campaign. As campaigns become increasingly decentralized and benefit from unofficial (and unregulated) volunteer efforts, it will be almost impossible to accurately estimate net campaign expenditures.

Mara Revkin is the editor of EgyptSource. She can be reached at mrevkin@acus.org.

Photo Credit: AP

Image: 628x471_0.jpg