Mapping Russia’s soft power efforts in Syria through humanitarian aid

Previous research has explored Russia’s quieter intervention in Syria through its use of humanitarian aid. Compared to its hard military actions that alienate much of Syria’s population, Moscow has used the incentive of aid to buy political loyalty and better promote its image. By mapping where Russia’s Center for Reconciliation of Conflicting Sides in Syria has delivered aid over an 18-month period (between 2018 and 2020), a picture of Russia’s soft power tactics in Syria can be formed. The findings suggest that Russia’s efforts are at best shallow and symbolic, though they also present avenues for engagement.

Buying friends and influence

Through a network of at least thirteen organizations, Russia’s influence in Syria’s humanitarian sector has steadily developed since 2016. Some of these organizations, such as The Russian Humanitarian Mission, have close ties to the Russian state, while others, such as The Russian Orthodox Church, are religiously affiliated.

One of the most active of Russia’s humanitarian entities has been the Center for Reconciliation of Conflicting Sides in Syria (CRCSS). This Ministry of Defense-linked entity is most famous for brokering surrender deals with opposition pockets around Damascus, Homs, and in southern Syria. Hidden within the CRCSS daily bulletins are details of its humanitarian work.

These statements show that the CRCSS conducted 735 humanitarian missions in 244 locations around Syria from November 2018 to April 2020. Taken at face value, this is a sizeable number. However, where and to who assistance was provided was driven primarily by political concerns.

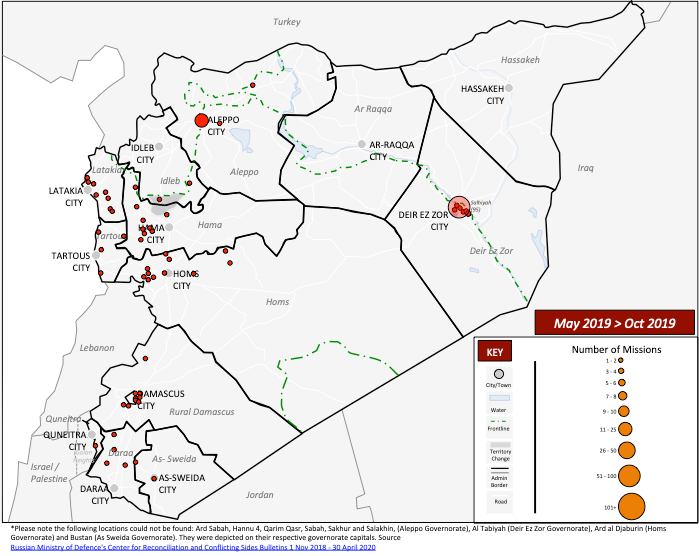

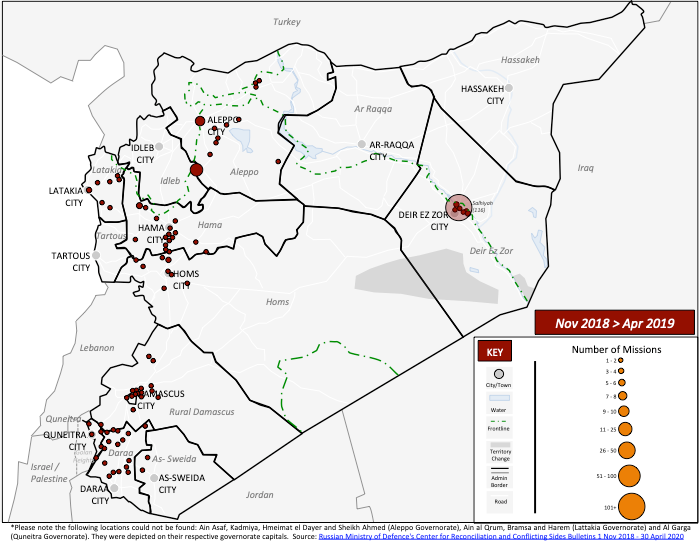

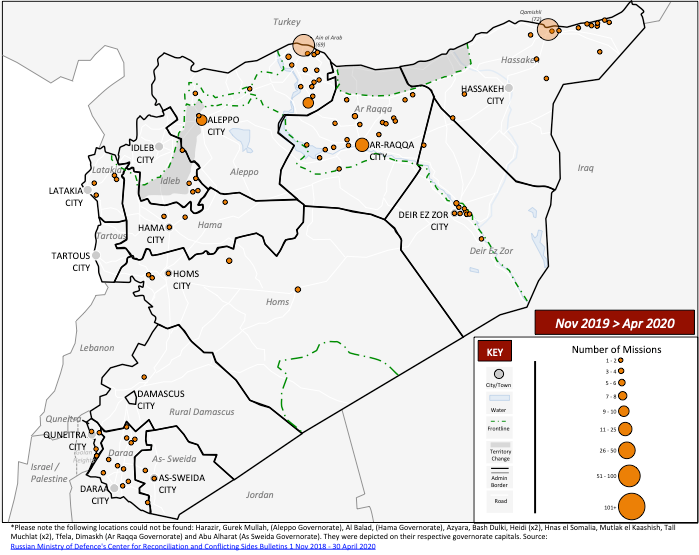

From November 2018 to October 2019, over half (224) of the 443 missions were focused around Deir Ez Zor City (Figure 1). Russia arguably prioritized humanitarian assistance, here, because the needs were high after more than three years of the city being besieged by the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS). Focusing humanitarian assistance to this area also helped undermine US military efforts in the region.

From November 2018 to April 2019, a third (82) of a total 257 missions were concentrated in or near communities recently recaptured by the Syrian government. These included southern Syria, areas around Damascus and Homs Northern Countryside, as well as areas south of Aleppo City. In a direct affront to the humanitarian principles of neutrality and impartiality, the same entity that provided humanitarian assistance to these communities was also a major catalyst in their violent surrender. Through its involvement in the reconciliation process, the CRCSS forced Syrian citizens to remain under government control, where they are now subject to the vagaries and violence of the security apparatus.

From April to October 2019, just 13 percent (25) of a total of 186 missions went to these former opposition areas, marking a significant drop. Instead, 30 percent (55) of missions were redirected to the government heartlands of Latakia and Tartous, the mountainous western Homs and Hama governorates, and the western areas of Aleppo City. Up until this point, many of these areas had been neglected by Western aid agencies because they had seen comparatively little impact from the conflict. The sudden shift of focus by the CRCSS was an attempt to buy loyalty from communities that were increasingly frustrated with the Syrian government’s lack of service provision, as well as the skyrocketing prices of basic goods and services. Deliveries to these regions also helped Russia boost its image with domestic audiences after receiving poor domestic approval ratings for its military intervention in Syria at the time.

Figure 1. Locations of Russia’s Center for Reconciliation of Conflicting Sides in Syria ‘humanitarian’ missions in Syria November 2018 – April 2020

After access to the Northeast Kurdish-dominated area became available in October 2019, the CRCSS’s activity exploded in the US-backed territory. Of 290 missions over the next six months, 77 percent (223) of the CRCSS’s activity focused on the Raqqa and Hassakeh governorates in addition to Aleppo’s Ain al Arab district. Aid to all other areas of Syria accounted for just 13 percent (39) of all the missions. The chance for Russia to further buy loyalty and showcase its soft power efforts at the expense of waning US influence in the northeast was too good an opportunity to miss.

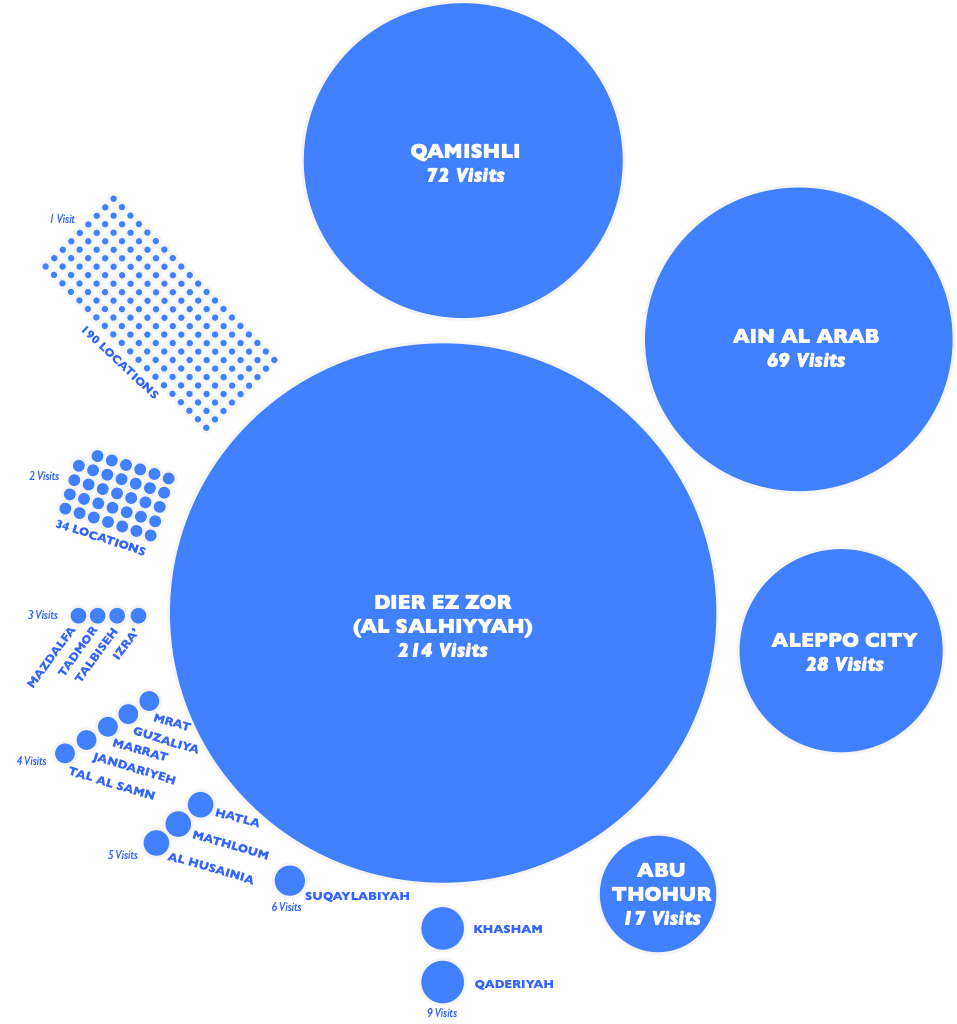

Undermining the humanitarian landscape

While 735 humanitarian missions in 244 communities from November 2018 to April 2020 may appear large, further analysis shows that Russia’s actions are largely shallow. A quarter of the CRCSS’s missions (190) in this 18-month timeframe were one-off visits. A further 139 missions could be described as limited, meaning that the CRCSS visited communities less than 10 times. Viewed another way, 98 percent (239) of the 244 locations the CRCSS visited in Syria between November 2018 and April 2020 were only ever symbolically served (Figure 2). Aleppo and Deir Ez Zor City were the only sites that experienced sustained aid delivery efforts from the CRCSS.

Figure 2. Distribution of humanitarian missions in Syria from Russia’s Center for Reconciliation of Conflicting Sides in Syria during November 2018 – April 2020.

While other countries, including the United States, also promote their narrative in Syria through the provision of aid, there is typically a degree of separation. For example, USAID’s budget for assistance in Syria is channeled through numerous United Nations (UN) agencies and international organizations—not the military. Entities that receive USAID funding are also accountable to their own boards and monitoring procedures, adding a further layer of protection. In contrast, the CRCSS is funded, directed, and accountable only to the Russian state.

Responding to Russia’s soft power efforts in Syria

There are two practical options to combat Russia’s soft power efforts in Syria. The first is to pressure the CRCSS to transfer its humanitarian actions to civilian actors. Ideally, this would be to entities that subscribe to accepted humanitarian principles and have experience in operating within a coordinated system. In Syria, this could be the UN, which despite its myriad issues, has one of the more robust coordination mechanisms set up for effective aid delivery. Better still, the CRCSS’s efforts could be handed over to the thirty-one—and growing—international non-governmental organizations conducting humanitarian operations in regime-controlled areas. These entities have a less tarnished reputation than the UN, but still benefit from its coordination and support and could provide an effective option for countering Russia’s shadow aid system.

A stepping-stone towards these options could be one of the other thirteen Russian humanitarian entities already operating in Syria. Some of Russia’s religiously affiliated organizations have more distance from state control and could find a pathway into the UN system through the latter’s affinity for organizations like the former. Others, like the Russian Humanitarian Mission or the Akhmat Kadyrov Foundation, would be harder to bring into this sphere given their explicit links to the state.

However, these suggestions still do not address the elephant in the room. The Bashar al-Assad regime will always control the humanitarian landscape in Syria. Any reconfiguration of Moscow’s humanitarian operations would have to navigate this complex system. Given Russia’s unique relationship with Syria, it’s perhaps here that it could have the greatest positive impact on Syria’s humanitarian landscape. By leveraging their close relationship with the regime, Moscow could play a key supportive role for humanitarians in a number of areas.

Russia could help with humanitarian access issues in Syria by pushing the government to streamline their currently cumbersome process for international non-governmental organization registration. Russia could also use their privileged position to advocate for freer humanitarian access within Syria, especially medically-focused assistance that responds to the current coronavirus crisis. Moscow could also help solve logistical bottlenecks by providing much needed specialist aid equipment, particularly for de-mining and unexploded ordnance clearance.

Creative solutions are needed in Syria now more than ever given the dire state of the economy and the implementation of the Caesar Act by the US government in June. Consequently, if they chose to, Moscow could contribute positively to bettering the lives of the Syrian people while still achieving their political goals in the country. This would ultimately create a lasting legacy for Russia in Syria that was not just built on death and destruction.

Marika Sosnowski is an admitted lawyer and research associate at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies, specializing in the Middle East.

Jonathan Robinson is an independent research analyst with nearly 10 years experience focusing on conflict analysis, humanitarian access and aid worker security in the Middle East. His views do not represent his current or previous employers.

Image: Russian soldiers stand near food aid being distributed to Syrians evacuated from eastern Aleppo, in government controlled Jibreen area in Aleppo, Syria November 30, 2016. The text on the bag, showing Syrian and Russian national flags, reads in Arabic: "Russia is with you". REUTERS/Omar Sanadiki