Tom Friedman’s column in The New York Times on December 7 supports an argument—that liberal forces in Egypt did less well than Islamists in the first round of elections because their anti-military protests had alienated “some more traditional-minded Egyptian voters, who still cling to the army as a source of stability”—that is emerging as part of the conventional wisdom. That is certainly a story that the SCAF would like to have told, but my conversations in Egypt last week paint a different picture. Most Egyptians with whom I spoke did not see supporting Tahrir demonstrators and voting in elections as two opposite choices; in fact, many did both, seeing electing a legislature as a necessary first step in dislodging the military from power. I think it would be misleading to suggest that the votes that the FJP and Salafis got were protest votes against liberals rather than votes deliberately for the Islamists.

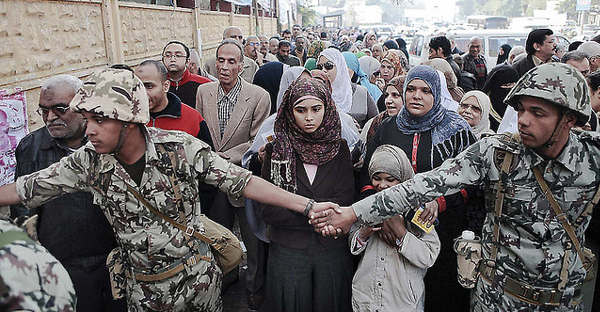

Where Friedman is correct is that the Tahrir protests “hampered the secular reformists in preparing to compete in the first round of elections.” And there is a specific reason for that. My observations last week in Port Said suggested that many, perhaps most, voters headed to the polls without knowing for whom they would vote. Therefore, the last-minute campaigning by parties and individual candidates, however illegal, was absolutely critical. Having a small army of volunteers deployed around polling places handing out small cards and pamphlets—as well as strategically-placed stations where voters could look up their specific polling place—probably made all the difference to voters befuddled by ballots full of unfamiliar names.

Let me give an example of how Tahrir factored in. George Ishak, one of the founders of Kefaya, was competing for a seat in Port Said with FJP member Ahram al-Shaer. This was expected to be a hard-fought race and to go to a runoff. It did not; al-Shaer was one of only a handful of candidates who won outright. The reason became clear in a conversation I had with one of the principal organizers of Ishak’s campaign, when I noted that in two days of visiting polls I had not come across a single volunteer or candidate agent for Ishak. The campaign had indeed organized a pool of such volunteers and even obtained official permits for candidate agents. But when the Tahrir protests broke out a week before elections, they all got on busses and went to Cairo to participate. Although the Tahrir protests were fizzling by the time the voting started on November 28, the Ishak campaign could not reconvene their volunteers in time. And so Ishak lost the race.

Thus, I suspect Tahrir’s negative impact on liberal candidates was due more to the fact that they took their eye off the ball and less that public sentiment turned against them. And it is unlikely that liberals would have been able to rival the Islamists in terms of numbers of volunteers in any case. Let’s see if they figure that out in time for next week’s second round.

The other point from Friedman’s column that needs discussion is his concern that Islamist parties have no idea how to “generate economic growth at a time when the Egyptian economy is sinking.” Certainly I share his concern about the economy, which is headed straight downhill and might be ripe for a crisis in as little as two months from now. And he is correct to worry that an Islamist-dominated parliament will scare foreign investors away, as well as many Egyptians.

What Friedman fails to mention, however, is that the Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party has by far the most well developed economic platform of any Egyptian political party, and that it is generally market-oriented and business-friendly. To lump the Brotherhood in with the Salafis and say that both “have been living underground, focused largely on what they were both against and confined in their ideology to platitudes like ‘Islam is the answer,’” is quite unfair. Unlike the Salafis, the Brotherhood has decades of experience in electoral politics (admittedly not free politics) and has worked harder than any other existing party on its platform, including the economic aspects. Having met recently with businessmen from the Brotherhood who worked on the platform, I can tell you that they care deeply about the economy and are realistic in their ideas about the need for foreign investment, tourism, etc.

All that said, I still have concerns that the Brotherhood will make poor economic policy decisions or resist good ones, but not because they don’t know any better. My concern is that they will be buffeted by demands from the population (for public employment and continued fuel subsidies, for example) and will not be as investment and tourism-friendly as they might otherwise be due to pressure from the Salafists. Those are pressures that any political party coming to power in this environment would face; the question is whether the Brotherhood will be better or worse at handling them than others would have been.

Michele Dunne is the director of the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East and an official observer of the first stage of the parliamentary elections. She can be reached at mdunne@acus.org.

Photo Credit: New York Times

Image: egyptian-soldiers-polling-station-EGYPT.jpg