Normally, the beaches of southern Tunisia are quiet in November. It is the start of the lean months, when few tourists arrive and the jobs which depend on them vanish. This year is different. Tunisia’s beaches have a new customer: Tunisians trying to go to Europe

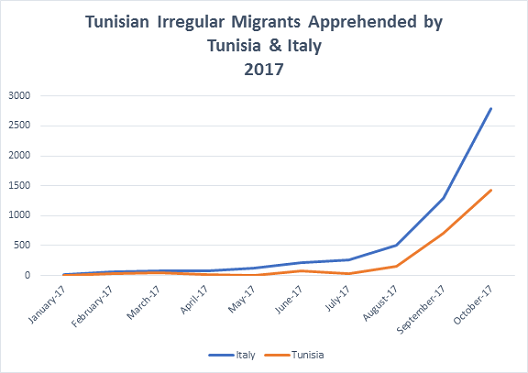

Between October 1st and November 8th, more Tunisians took to the seas than in 2015 and 2016 combined, with Italy and Tunisia detaining 4,709. In total, more than 8,700 Tunisian migrants have been caught by Italy and Tunisia in 2017. There are suspicions this represents only a fraction of those who have left.

The rise in migration is as unexpected as it is dramatic; it became clear with Italian interdictions roughly doubling each month since July. By October, 45 percent of irregular migrant arrivals in Italy had departed from Tunisia. However, few in Tunis seemed aware of the surge until a migrant boat sunk in early October, killing 45. Afterwards, irregular migration became a high-profile issue in Tunisia. But, there is little agreement on what is causing the surge.

The catalyst for the surge seems to differ from the last significant episode of Tunisian migration, which occurred in the wake of the 2011 Jasmine revolution and saw over 28,000 young men and women departing for Italy in a matter of months. In that instance, post-revolutionary distraction and the weakness of Tunisia’s law enforcement enabled the migration surge. There is scant evidence that law enforcement weakness is a factor now.

There is media speculation that the Tunisian migration surge was connected to the Libyan militias blockading their country’s departure beaches in July and August, which is right when the Tunisian migration surge started. The Libyan militias’ actions led to a drop in migrant departures. However, that correlation seems spurious. The fact is that the people being apprehended by Tunisian and Italian border patrols are predominately Tunisian, not Sub-Saharan or from other north African countries. The rise in Tunisian migrant apprehensions has occurred both in Tunisia and Italy, indicating it is not a change in routes but in absolute number. There is also little evidence that large numbers of sub-Saharan migrants going through Libya are crossing the border from Libya to Tunisia, an influx that would be difficult to hide.

Under pressure

To understand why migration is increasing, the best place to start is with the origin of many of the apprehended migrants: Tunisia’s southern and interior regions, such as Kasserine, Sidi Bouzid, and Tataouine, to name a few. These regions have a long history of economic and political marginalization and frustration; which occasionally sparked mass unrest. The 2011 revolution caught fire in these regions with calls for dignity and economic justice long before they swept the streets of Tunis and other coastal cities. However, what is much less discussed is that since the revolution, the economic and political marginalization fueling frustration in these regions is unresolved, and for some has worsened. For Tunisia, 2017 has been particularly rough.

This is clear in Tunisia’s southeastern governorates of Tataouine and Medenine. One percent of the population, at least six hundred men, from Tataouine Governorate’s capital city, departed in only a few weeks in September. More from the two governorates have since followed. The livelihoods of a large percentage of the population in this region depend on the informal economy, which is closely tied to licit and illicit forms of cross-border trade with Libya. The sheer scope of the informal cross-border trade is staggering. Until recently, gasoline smuggling from Libya employed 5,600 people and generated 320 million Tunisian Dinars per year.

This summer, gasoline smuggling on the Tunisia-Libya border collapsed. This was largely due to the emergence of smuggling as a potent political issue in western Libya. A deepening economic crisis, rising prices, and frustration over the diversion of fuel by smugglers have led a growing number of Libyans to protest, push local authorities to crack down on smuggling, or embrace militias espousing an anti-crime narrative. Action against smugglers has occurred even in Libyan cities like Zuwara and Nalut where fuel smuggling was an economic mainstay. Tunisian efforts to buttress border security in the wake of terrorist attacks in Tunis and Sousse also played a role, making smuggling more difficult, dangerous, and expensive. The collapse of the cross-border gasoline trade has had a significant impact in Tunisia’s southeast, putting thousands of gasoline smugglers and informal vendors out of work. This has tripled the price of gasoline in the southeastern governorates, putting pressure on household budgets already squeezed by high inflation and a rapidly depreciating dinar.

At the same time, police raids have confiscated the assets of multiple members of the informal financial sector in Tunisia’s southeast, in the context of the government’s ‘War on Corruption’. These informal money lenders play a vital role in providing funds, credit, and connections for informal trade operations throughout the Maghreb. This security response to a complex economic issue, has not been tied to the formalization of the informal monetary system, but to the contraction of its capital base, further depressing the region’s economy.

In general, the growing pressure on the informal economy has not been accompanied by a growth in opportunities in the formal sector for the newly unemployed or underemployed. The conditions for private investment remain poor, while the majority of the new ‘Tunisia 2020’ investment projects go to the coastal and northern regions. While tourism, struggling after the 2015 attacks in Sousse, has bounced back to a degree, it only provides a season’s income for young men. Fishing, another traditional income stream in the southern coastal regions, has had a difficult year as an invasion of blue crabs has led to a double digit drop in fishermen’s livelihoods, leading many to turn to migrant smuggling or sell their boats to other traffickers.

International policy has not helped, and at times worsened, the situation of many of those now leaving the country. Pressure by the IMF for Tunisia to adopt an austerity-focused economic reform program has left little room to consider development options for marginalized regions. IMF demands to cut thousands of public sector jobs will further strain the far larger number of families who depend on income from these jobs for survival. International actors pushing to open Tunisia’s economy could exacerbate the imbalance of opportunities within the country.

Pessimism and protest

Economic hardship is not a new phenomenon in southeastern Tunisia. However, what has been particularly striking in recent conversations with young men in these regions has been the sense of resignation and growing pessimism. The worsening economic situation has not just depressed incomes, it has led to a growing conviction that economic accumulation, and hence upward mobility, are not possible for ordinary citizens. Faith in a central promise of the revolution is dissipating rapidly. “I just want to make enough money to live, just to build a house and buy a car. That is my whole ambition, that’s not much. That is my right, but it’s a right that we don’t have,” noted a young man in Medenine, before quoting a popular proverb: “We accepted the suffering, but even the suffering doesn’t accept us.”

There is little expectation that the government will deliver on repeated promises of economic development, jobs, and a better life. In the spring and summer of this year, frustration with the government drove a series of large protests across Tunisia. In the governorates of Kairouan, Zaghouan, and Kef, large crowds took to the streets to demand economic development, jobs, and dignity. In the southeast, protesters demanding jobs took over an oil pumping station at El Kamour in Tataouine, leading to a three-month blockade, violent clashes with security forces, and one death. The standoff at El Kamour ended in a similar way to the protests earlier in 2017: government promises of economic development and jobs without coherent proposals. With little evidence that jobs will emerge, many in the southeast and other marginalized regions have no choice but to look for other alternatives.

Migration is a displacement, not a solution

Tunisia’s spring and summer of protest appear to have given way to a fall and winter of departures. The drivers of both the protests and now migration are similar: frustration over regional inequality, worry over a worsening economy, and anger over a lack of jobs. The economic situation in Tunisia has not bottomed out yet. However, Tunisians have little faith that the government can resolve the economic challenges facing the country. Liquidating family savings to fund a husband or son’s trip to Europe is a dangerous gamble, but for a growing number of Tunisians it appears to be a gamble worth making. “We are already like refugees in Tunisia” another young man told me. “We have our citizenship, but right now in Ben Guerdane, that only means duties—there is nothing here for us.”

The political and economic impact of rising migrant departures are complex. Tunisia’s relations with Italy do not appear to have suffered yet. There may well be a hope in Rome that most Tunisian migrants quickly pass through, heading north to the large Tunisian diaspora communities in northern Europe. This sentiment could worsen, especially given the Italian public’s souring sentiment on migrant arrivals.

Within Tunisia, rising migration provides an outlet for the unemployed, and in the short term may be the one thing that keeps a combustible social situation from exploding. This may give the government necessary breathing room to address difficult economic and social problems. Rising migration is not a panacea in and of itself. It will not solve the problems of regional inequality, economic opportunity, and dignity. Absent government action to address these points, reckoning with them will simply be punted to the future.

Matt Herbert is a Ph.D. candidate at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy and a Research Fellow with the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. Based in Tunisia, his doctoral research focuses on security-sector reform, smuggling, and organized crime in North Africa. Follow him on Twitter @mherbe01.

Max Gallien is a Ph.D. candidate in International Development at the London School of Economics, specializing in the Political Economy of North Africa. His doctoral research focuses on informal economies and smuggling networks in Tunisia and Morocco. Follow him on Twitter @MaxGallien.

Image: Photo: Migrants are seen on a boat after they were rescued by Tunisian coast guard off the coast of Bizerte, Tunisia October 12, 2017. Picture taken October 12, 2017. REUTERS/Zoubeir Souissi