Parliamentary elections won’t rescue Algeria from its legitimacy problem

Arriving on the heels of two years of overt popular contestation, Algeria’s June 12 parliamentary elections will not suffice to resolve the country’s deep political impasse.

The upcoming polls are the latest attempt by President Abdelmadjid Tebboune’s administration to claim a mantle of legitimacy it sorely lacks. Both Tebboune’s election in December 2019 and a constitutional referendum last November appeared to deliver the results he and his sponsors in the country’s powerful security forces sought. High levels of abstention and protest, however, highlighted a wide gulf separating Algerians from their leaders (in the country of forty-three million, fewer than one in seven eligible voters voted for the constitution, which passed nonetheless).

Algeria’s rulers have long dismissed this gulf but it became undeniable in 2019 when the Hirak protest movement erupted, bringing an end to the twenty-year reign of Tebboune’s predecessor, Abdelaziz Bouteflika. The mass demonstrations, which were triggered by Bouteflika’s choice to run for a fifth presidential term but were fed by years of accumulated frustration and indignity, also plunged the country into a political deadlock. For two years, gray-haired authorities have faced off against protesters drawn from a population that is much younger, hungry for opportunity, and less accepting of Algeria’s longstanding isolation.

A tainted parliament

Under the pretext of the new constitution, in February, Tebboune dissolved the National Popular Assembly (APN), the lower house of Algeria’s parliament, ending deputies’ normal five-year mandates a year early. The move fit with authorities’ campaign of pseudo-reforms designed to placate discontented citizens and undercut calls for more fundamental change.

The APN was a natural target for this campaign. Many Algerians have long viewed it as a rubber-stamp body and publicly derided its members as incompetent and opportunists. Deputies enjoy high salaries and perks, which allegedly total over twenty times the country’s minimum wage and are a perennial source of resentment. The ruling National Liberation Front (FLN) and National Democratic Rally (RND) parties—prime targets of the Hirak’s ire—have dominated the parliament for decades. Whenever the country’s ragtag opposition parties have managed to win seats, parliamentary rules have prevented them from exercising meaningful influence over policymaking.

From this meager starting point, the chamber’s reputation sank further still in September 2020, when former Parliamentary Vice President Baha Eddine Tliba admitted in a corruption trial to paying FLN leaders some $500,000 for the top spot on an electoral candidate list. In total, he estimated, such deals netted senior party officials over $20 million in Algeria’s last parliamentary elections.

Crackdown on dissent

Among the Hirak’s ranks, few were disappointed to see the tainted parliament dissolved.

But the rush to elections clashes with the vision of sweeping political renewal the movement has advocated since its earliest days. So too does the new constitution, which leaves the longstanding imbalance of power between Algeria’s executive and legislative branches intact. For these reasons, many Hirak activists have announced plans to boycott the upcoming polls and continue protesting.

Those protests number at just a fraction of the Hirak’s massive early turnouts. While the movement maintained steady participation throughout its first year, activists paused demonstrations for the coronavirus pandemic and have struggled to regain their early momentum since restarting marches in February. Recent protests have been largely confined to major cities and a few opposition strongholds, namely in and around the northern Kabylie region.

Outside the dedicated core of protesters, many others grew tired of the weekly marches. Circumstances have also changed since the movement began. “The economic fallout from COVID-19 has changed priorities,” one friend wrote me from Algiers this spring. “People prefer stability.”

Others have been discouraged by internal strife within the leaderless movement, including over the place of women’s rights in the Hirak’s agenda and fears of Islamist infiltration. Authorities have stoked these fears through a media campaign to discredit the peaceful movement by linking it to various extremist and separatist movements. While such claims might appear absurd, in a country still traumatized by a decade of extremist violence in the 1990s, they remain effective.

Still, other Algerians sympathetic to the Hirak’s goals have chosen to stop protesting in the face of escalating repression, which began during the Hirak’s hiatus and continues this year. Thousands of peaceful protesters, journalists, academics, and ordinary citizens have been arrested, independent media outlets have seen their websites blocked, civil society organizations have been shuttered, and detainees have allegedly been tortured by security services while in custody. In May, authorities unveiled new restrictions on protests just as they redoubled efforts to stamp out the weekly Hirak marches entirely. Over two hundred political prisoners currently sit in Algerian jails, according to activists.

Lackluster campaigning

In addition to these issues, there is no shortage of policy challenges on which prospective legislators might campaign. Unemployment is rampant, oil revenues have slumped, reserve funds have dwindled, and many are frustrated with the government’s handling of the pandemic, including lagging on vaccine rollout compared to its North African neighbors.

Amid these challenges, Algeria’s traditional political players have struggled to inspire voters. The FLN, RND, and their allies are in disarray after corruption trials—another attempt by authorities to appease protesters—decimated their upper ranks. Opposition parties—most of which enjoy little popular following anyway—have largely opted to boycott the elections. In addition to calling for more fundamental change, they claim that the elections will suffer from the same fraud that they allege has long plagued polls in Algeria. Moreover, the September 2019 creation of an independent election authority seems to have swayed few minds on questions of electoral integrity.

With most traditional parties sidelined, new local alliances have emerged, including many new faces. Unlike in past years, independent candidate lists outnumber party-affiliated lists, clouding the electoral landscape. Close scrutiny of the independent lists, however, reveals a strong presence of FLN- and RND-affiliated candidates. Islamists also feature prominently, prompting speculation that they could seize a majority in the new parliament.

The official three-week campaign period, which began May 17, has been lackluster, with relatively few rallies, posters, or other typical signs of pre-election jockeying. One of the campaign’s few noteworthy moments to date was a gaffe by a minor party leader who compared the women candidates on his party’s lists to “the finest strawberries.” Electoral law changes have weakened a 30 percent women’s quota imposed in 2012, which will almost certainly result in decreased representation for women in the next parliament.

Online, young Algerians have amused themselves by mocking election posters and decrying candidates as opportunists merely chasing lavish salaries and political access. For the first time, this year authorities have promised substantial campaign stipends to candidates under forty years old, which critics claim will leave the new parliament compromised even before it is seated.

Low stakes, for now

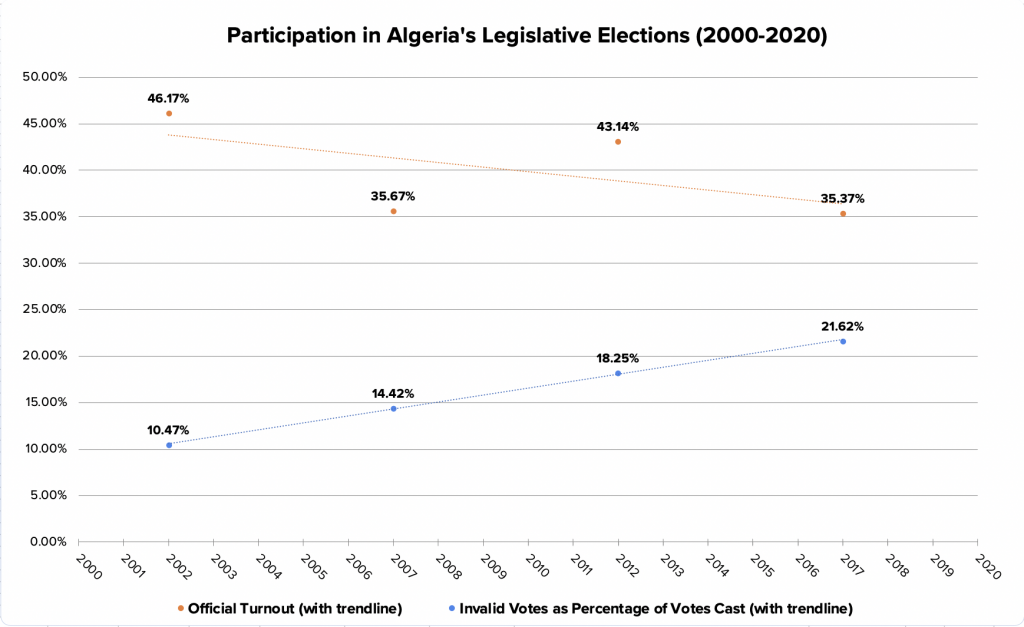

Algerians who do believe in the integrity of the country’s election results may look to judge the upcoming polls by two key metrics: turnout and invalid ballots. In recent decades, official legislative election results have shown a general decline in participation and a steadily rising rate of invalid ballots—a common form of protest vote in Algeria.

Many Algerians place little value in these official statistics. Yet, the figures are of central importance to President Tebboune and other members of Algeria’s governing class. Their efforts to encourage turnout in the June 12 elections are just one step in a larger quest for legitimacy. Today, the generation of independence-era heroes who ruled Algeria for decades is ceding power. The legitimacy they drew from the liberation struggle long served to excuse their faults. Today, their departure leaves those who follow them facing a critical question: what can we offer Algerians today to earn their loyalty?

While critical to the country’s long-term prospects, it’s a question that won’t be answered through this week’s elections.

Andrew G. Farrand lived in Algeria from 2013 to 2020, managing youth development programs. He is the translator of Zohra Drif’s Inside the Battle of Algiers (2017) and author of The Algerian Dream (forthcoming this summer). He blogs at Ibn Ibn Battuta.

Image: Demonstration of the 112th Friday in Algeria. The demonstrators of Hirak, a popular protest movement born on February 22, 2019 marched on Friday in the streets of Algiers to reiterate their refusal to the early legislative elections of June 12 and demand the independence of the judiciary as well as the release of the Hirak detainees. Algerian protesters raise a national flag as they march demanding political change in the capital Algiers, Algeria, on April 9, 2021. Photo by Louiza Ammi/ABACAPRESS.COM