Russia in the Middle East: A source of stability or a pot-stirrer?

This article is part of a strategic collaboration launched by the Atlantic Council (Washington, DC), the Emirates Policy Center (Abu Dhabi), and the Institute for National Security Studies (Tel Aviv). The authors are associated with the initiative’s Working Group on Chinese and Russian Power Projection in the Middle East. The views expressed by the authors are theirs and not their institutions’.

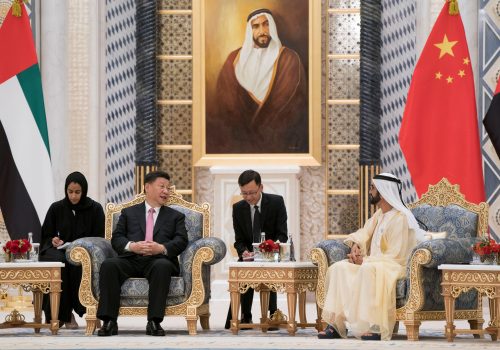

The four-day visit by Russia’s Foreign Minister, Sergei Lavrov, to the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, and Qatar in March 2021 merited few global headlines. It did, however, underline several trends in relations between Russia and the Middle East. First, the Gulf states are cognizant of Russia’s influence and remain keen to cultivate ties. Lavrov, for instance, was presented with one of the UAE’s highest honors. Second, Russia’s high-level engagement with the region contrasts with the more reticent approach by the United States; Saudi and Emirati weapons sales approved by the Donald Trump administration continue to languish, the Caesar Act has stymied Gulf efforts to participate in Syria’s rehabilitation, and many of the region’s leaders have yet to speak directly with President Joe Biden. Third, the tripartite meeting between the foreign ministers of Russia, Turkey, and Qatar in Doha on March 11 was evocative of extending the Russian-Turkish “frenemy relationship” to yet another theatre in the Middle East.

Lavrov’s Gulf tour—followed by a rare meeting in Moscow with Lebanon’s Hezbollah delegation on March 15 and a meeting with Israeli Foreign Minister Gabi Ashkenazi two days later, as well as Lavrov’s anticipated visit to Iran—exemplify the complexity of Russian foreign policy in the region. These events and the summoning of the Russian ambassador in Washington for consultations at the Kremlin make this an opportune time to consider Russia’s role in the Middle East. We present different perspectives below from the US, Israel, and the Arab world.

The US perspective

The Middle East has always been part of Russia’s vulnerable underbelly: a region the Russian state sought to secure as it pushed to play a key role in European politics and gain great power recognition. Since officially coming to power in May 2000, if not before, Vladimir Putin worked to return Russia to the Middle East as part of his zero-sum approach to international politics. Putin’s military intervention in Syria in September 2015 to prop up Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad shocked and surprised many, but it was the logical conclusion of years of broader aims to deter the West in a context of dithering Western policies.

Unlike the former Soviet Union, Putin cultivated and continues to cultivate all major actors even as they oppose one another. It is a more pragmatic, flexible approach than that of the Soviet Union’s ideological approach which had clear allies and adversaries. Putin’s strategy has been successful especially given the ambivalence of Western commitments to the region. Thus, Moscow maintains good relations with Iran and its proxies, Israel, and the Gulf—to name but a few—and tells each side it can play peacemaker. Moscow utilizes all tools in its state toolkit to build pragmatic leverage—not only through the military but also para-military, intelligence, trade, and soft power.

Moreover, Putin had come to perceive the West as weak—especially after President Barack Obama drew but did not enforce a red line in Syria in 2013—and it is likely for this reason he felt confident to intervene in Syria militarily. American ambivalence helped Putin make inroads in the region. Moscow’s approach to the Middle East is zero-sum: for Putin to win, the West has to lose. Putin is also not seeking genuine stability—on the contrary, low-level instability puts him in an advantageous managerial position.

Syria is the epicenter of Kremlin activity, which Putin uses as a springboard to project power throughout the region and Europe and Africa. Nothing makes as clear a statement about Moscow’s interests as the recent unveiling of a monument to the patron saint of the Russian army, Prince Alexander Nevsky, at the Russian Khmeimim airbase in Syria. This demonstrates Russian commitment on a symbolic as well as practical level. And symbolism resonantes both in the Middle East and Russia.

Of course, militarily, Russia is in Syria to stay for at least the next forty-nine years, as per an agreement between Moscow and Damascus. In this time, Moscow continues to take practical steps on the ground to vie for influence in Syria and push for its preferred outcome. Syria’s strategic location on the Eastern Mediterranean allows Russia to project power into NATO’s southern flank and, more broadly, southern Europe. In this context, the oil-rich and strategically-positioned Libya was the next logical step, as I have written in early 2017. Indeed Russian activity there became more explicit in recent years both on the diplomatic front—as Moscow aimed to position itself as a mediator—and with more visible and increased deployment of so-called private military contractors, such as the Wager Group.

While Moscow’s interests are primarily geopolitical, there is also a commercial aspect—mostly concerning energy and arms—in addition to cultural and religious dimensions. And, although Putin works to build ties with everyone—not an easy balance to maintain—the balance is still tipped in favor of anti-American forces, Iran and its proxies, and Assad.

The US under Biden has yet to announce its Syria policy, but Damascus is unlikely to be a priority, which will only continue to help Putin. While many details are unclear, from a broader perspective, the US continues to deprioritize the Middle East in favor of great power competition with China and Russia in other regions. In contrast, Moscow sees the Middle East as a prime arena for this joust. If this trend continues, Russia will continue its already deep convergence with Iran and its proxies and will ultimately have the final word on Syria’s future. This could lead to a more explicit rise of a Russia-Iran-Assad nexus and transform the Middle East in a way that could create more vulnerabilities for the West and its allies, both in the region and in Europe. Such a scenario could only hurt broader American competition with China and Russia.

Dr. Anna Borshchevskaya is a senior fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy where she focuses on Russia’s approach to the Middle East. She is also the author of the upcoming book, Putin’s War in Syria: Russian Foreign Policy and the Price of America’s Absence.

The Israeli perspective

While seeing itself as a part of the Western camp and a close ally of the US in the Middle East, Israel does not view Russia as an adversary. The two countries dissent on many core issues in their Middle Eastern policies but prefer to focus on an agreeable agenda.

One million Russian-speaking citizens who repatriated to Israel after the disintegration of the Soviet Union contributed to the development of intense people-to-people connections between Israel and Russia, including economic and cultural cooperation. The national strategic narratives of the two countries are interconnected. The Israelis cherish the Soviet-Russian role in the defeat of Nazi Germany and stopping the Holocaust. The Kremlin appreciates the Israelis speaking loudly on this matter, as that victory entitles Russia to an exclusive international status—even though the Soviet Union’s role in World War II is currently a highly contested subject between Moscow and Eastern European countries.

More recently, Israel took a cautious position on the Russian-Western rupture following the 2014 annexation of Crimea. It neither actively condemned Russia nor joined sanctions against it, and kept on high level meetings with Russian officials. President Putin highely appreciates Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s position, compared to sanctions and disengagement from most other pro-Western capitals.

Russia’s decision in 2015 to officially intervene in the Syrian civil war created a new strategic and operational environment for Israel. It also made the Syrian theater the most crucial bilateral issue Israel has with Moscow. Russian troops became a constant feature on Israel’s northern frontier in the Golan Heights, where the Israel Defense Forces is struggling to prevent a long-term military presence by Iran and militias controlled by its Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Despite backing the Assad regime and fighting together with Iran and Hezbollah for this cause, the Russians do not support their aggressive activities against Israel. Jerusalem values Moscow’s relative neutrality and its turning of a blind eye on Israeli strikes against Iranian targets in Syria. Both Moscow and Jerusalem are keen to diminish the threat of a direct clash by their respective militaries similar to the incident in 2018, in which Syrian air defense accidentally shot down a Russian reconnaissance plane with fifteen officers on board following an Israeli airstrike. Russia’s accusation that Israel had been responsible for the accident led to a major crisis in bilateral relations.

The Israeli-Russian ties may appear to be a close partnership, but this overlooks the deep disagreements about Syria’s future, the Iranian nuclear file, Russian arms sales to the region, and the Palestinian issue. Although Israel has not entirely relinquished hope that Moscow’s leverage over Assad may help drive the Iranians out of Syria, it mainly relies on itself and supports the US military presence there. It also considers Russia to be over-protective of Iran’s escalatory steps in nuclear enrichment and ending the arms embargo (as the Russian military industrial complex seeks to safeguard its market share in Iran). In addition, Jerusalem is not aligned with Moscow’s mediation vis-à-vis the Palestinians and mainly takes into consideration the US position.

Israel’s primary interest in preserving its strong bond and defense cooperation with the US constrains its contacts with Russia. Yet its leadership understands that active public engagement with Putin will help Israel retain its freedom of operations against Iranian entrenchment in Syria.

Lt. Col. (ret.) Daniel Rakov is a research fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv, focusing mainly on Russian Policy in the Middle East and Great Power Competition in the region.

The Arab perspective

The current Russian policy in the region is based on two elements: (1) world politics in the coming four years will be chaotic and unpredictable and (2) a conviction that US policy will lead to a diminished presence in the Middle East. Although the Biden administration is reviewing Washington’s foreign policy approach, Russia believes that the process will reduce US focus on the Middle East. Both of these elements are likely to provide Moscow with an opportunity to expand its presence and enhance the importance of its role in the region

Moscow harbors no illusions about replacing Washington in the region. Such a thing is not on the Kremlin’s agenda because it is fully aware that this is impossible to achieve. What Russia seeks is to fill the vacuum left by others. This is the essence of Russia’s foreign policy over the past few years.

This explains Moscow’s inclination to actively expand its military presence in the Middle East and North Africa in recent years. It is not just about Syria, although Damascus is undoubtedly Russia’s priority in the region. This is because the gains achieved there cannot be replaced or dispensed. Russia has also reached a deal with Egypt to create a Russian Industrial Zone in East Port Said and another with Sudan to establish a logistics support center for its navy in Port Sudan. Russia also has indirect military involvement in Libya via the Wagner Group, a military contracting firm.

Arab countries have found themselves facing a new reality since the war in Syria. Now they have a new regional neighbor with a long-term military presence in Syria and significant engagements with both Iran and Turkey. While realizing that the range of Russian interests has noticeably expanded, the almost collective position of the Arab region is to abide by international law. This is not limited to Arab Gulf countries but includes the whole Arab region from North Africa to the Levant—with the exception of Syria. For instance, no Arab country has recognized the annexation of Crimea. In exchange, Arab countries have not engaged in policies that impose unilateral sanctions on Russia.

The impact of Russia’s activities in the region and how it shapes relations with the Great Powers are numerous. First, Russia does not have a comprehensive strategy to deal with regional issues. Moscow’s measures are based on tactical moves to enhance its presence. Unlike China, for instance, Russia does not have a soft power project or mechanisms to enhance investments. Instead, Moscow seeks to attract limited investments to deal with the policy of sanctions imposed on the country.

Second, Russia seems to be more interested in engaging in an existing crisis than in shaping its solution. This indicates that Moscow does not look at any crisis as it really is but through how they impact Moscow’s relations with other parties to the conflict. Russia is unwilling or unable to help find solutions to problems. Instead, it makes proposals to keep itself engaged in dialogues. Such examples include: proposing an international peace conference or reviving the quartet on the Middle East; suggesting a joint security mechanism in the Gulf; and sponsoring dialogues among Libyan parties.

In addition, there is a dialectical relationship between the US and Europe’s endeavor to move into Russia’s sphere of influence and Moscow’s presence in the region. The more NATO expands eastward by including new member states from the former Soviet Union or appears to encourage color revolutions in Russia’s neighborhood, the more Moscow becomes involved in the region.

Finally, Moscow’s behavior is informed by US foreign policy trends. In other words, while the US pressures its allies in the Middle East on human rights issues, Russia demonstrates more flexibility in this regard and places no conditions when parties need to purchase weapons or improve military capabilities. In this sense, Russia leverages policy trends to its advantage and strengthens its prospects of becoming an active player in the region, but not as an ally that can replace the US in the Middle East.

Raed Wajeeh is a senior researcher at the Emirates Policy Center.

Dr. Li-Chen Sim organized this article and authored the introduction and conclusion. Li-Chen Sim is an Assistant Professor at Khalifa University in the United Arab Emirates.

Conclusion

The perspectives above demonstrate the nuances of the role of Russia in the region. The diversity of the Middle East and its sub-regions—in terms of economic development, ambitions of its leaders, and security priorities, to name a few—offer a myriad of opportunities but also complex challenges for Russian influence. Russia is aware of its material constraints, especially relative to the US and China. Yet, it feels the inexorable pull of derzhavnost—a feeling of being entitled to great power status.

The interplay of these regional and endogenous contexts implies scope for conflict among the Great Powers but equal room for cooperation on selected issues. On which issues are cooperative relations most forthcoming? Where lies the greatest divide among the Great Powers in the Middle East? What scope is there for agency by states in the Middle East? Or is the region destined to be a “penetrated” one? This Working Group will be taking an in-depth look at these and other questions over the next few months.

Image: Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov met with Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed, who awarded him the Order of the Union, one of the UAE's highest civilian honors. Mohamed Al Hammadi / Ministry of Presidential Affairs