Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has repeatedly been compared to former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, but his own words suggest that the late president Anwar al-Sadat – who won popularity early in his tenure but ended his life unpopular and resented – may be the more instructive comparison.

Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has repeatedly been compared to former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, but his own words suggest that the late president Anwar al-Sadat – who won popularity early in his tenure but ended his life unpopular and resented – may be the more instructive comparison.

In the first of Sisi’s televised interviews, he was asked if he saw himself as a new Nasser.

“I wish I was like Nasser,” he replied. “Nasser was not, for Egyptians, just a portrait on walls but a photo and voice carved in their hearts.”

It was an understandable question to ask. In the Egyptian press, Sisi has been repeatedly compared in laudatory and glowing terms to the charismatic leader of the Free Officers, who brought British colonial rule to an end in 1952.

“He gave off an air of dignity that reminded me of the extraordinary leader Gamal Abdel Nasser,” wrote Yasser Rizq, the editor-in-chief of Al Masry Al Youm, Egypt’s leading daily, concluding an extraordinarily sycophantic article entitled “The General Sisi I know”.

Actress Lubna Abdel Aziz wrote in Al-Ahram that Egyptians’ love for Sisi – with “bronzed, gold skin, as gold as the sun’s rays,” apparently – expressed their enduring affinity with the army. “Gamal Abdel-Nasser is a recent example, even when he ruled with the firm grip of a military dictator,” she continued.

Even Nasser’s own son Abdel Hakim and daughter Hoda got in on the act, comparing Sisi to their father .

The foreign and English-language press has also published numerous articles analyzing the comparison, always in more critical terms. Several noted that Sisi lacks both the intention and the economic resources to deliver drastic improvements to the lives of the poor through redistribution.

“If he were to undertake the sort of sweeping reforms of his predecessor, it would require seizing assets not just from wealthy landowners, but from the military itself. For this reason, his instincts have so far tended to be conservative — not revolutionary,” Max Strasser wrote in Foreign Policy.

It is, however, odd that the most popular point of comparison for Sisi is Nasser at all. Nasser’s successor, Anwar al-Sadat, is a far better analogy – not least because it is Sadat with whom Sisi, in his unguarded moments, has shown himself to be preoccupied.

Sadat is mentioned by Sisi at least three times in the leaked material which has emerged since June last year, in terms which indicate both personal admiration and political affinity.

By contrast, Nasser is not mentioned once: Sisi might find the comparison flattering or useful when it is proffered, but there is no evidence that he personally relishes it.

Most widely reported among Sisi’s leaked references to Sadat is the dream he recalled in an interview with Rizq of Al Masry Al Youm

“I was with Sadat,” Sisi said, “and I was talking to him, and he told me ‘I knew that I would be the president of the republic’, and I said to him ‘I also know that I’m going to be the president of the republic’.”

Rizq then asked Sisi if he feels that, like Nasser, he could become president. “There’s a prayer I always say, that I could be that,” Sisi replied. But it was his interlocutor who introduced the figure of Nasser, not Sisi himself.

It is the economic challenges which Sadat faced, and which festered unsolved for the 30 years of Mubarak’s rule, and the responses to those challenges which most clearly link Sadat and Sisi.

In his thesis, entitled “Democracy in the Middle East,” written while a student at the United States War College in 2006 and leaked online last year, Sisi wrote with concern about Egypt’s weakness under Mubarak, while also praising reforms instituted by Sadat.

“The overall economic system is weak and does not provide an incentive for the population to pursue education. Excessive government controls and bloated public payrolls stifle individual initiative and tends to solidify the power base of ruling political parties. In Egypt, under President Sadat, government controls were lifted in an effort to stimulate economic growth; however, these efforts have not blossomed under President Mubarak.”

A number of economists and historians argue that Sadat’s infitah – “opening up” of the economy – in fact created a layer of big businessmen dependent upon political patronage, but did not really open up the economy at all, still less generate sustainable growth.

In a separate leaked recording, Sisi was again heard discussing the aborted economic vision of Sadat, and arguing that what was begun under him must be resumed – this time on the crucial issue of subsidies, which swallow a gargantuan slice of the government’s annual budget.

“Even if it gets to the point that the people of the country do not have something to eat,” he said, ” in order to make this decision [to cut subsidies]… [He trails off and resumes] Former President Sadat attempted to make this decison on 1977. Since then everyone is frightened of this decison and they say ‘Didn’t you see what was happened in 1977?'”

Sisi went on to say, no doubt correctly, that Egypt cannot continue to bear the weight of the current subsidies bill. In public interviews since, he has expressed support for the consensus idea that subsidies must be phased out in such a way that the poor are protected, while the richer are increasingly asked to pay their own way. His private words, in leaked recordings, have been drastically less sympathetic.

Why is the Sadat comparison not common? Probably because, although there are undoubtedly Sadat fans amongst Egyptians, he is far less popular than Nasser. Sadat presided over a decade in which the slowing world economy and mounting domestic troubles led to rising prices and an erosion of the rising standard of living and, for many, hopefulness that was Nasser’s bequest.

Many Egyptians perceive Sadat’s era – largely correctly – as a time in which an independent foreign policy was sacrificed for a strategic relationship with the United States, and in which state capitalism began to morph directly into crony capitalism, without ever passing through the phase of an equitable social market.

There are many points of dissimilarity, of course. Unlike Sadat, who rapidly pivoted to the United States in international relations, Sisi looks set to continue the policy of “diversifying” Egypt’s foreign relationships, although no doubt within the fundamental limits of the orientation toward the United States set by Sadat.

Sadat mollified the state’s stance toward the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamists, releasing many of their political prisoners in order to provide a bulwark against the left. Sisi’s approach has been more like that of Nasser who was willing to work with the group at first before turning on them harshly, and having them outlawed.

Sisi does, however, project an impression of personal piety most closely comparable to that of Sadat, who took to calling himself the “Believer President” and who, like Sisi, bore a zebiba, or prayer mark, upon his forehead—an outward sign of piety resulting from regular prayer.

But as Sisi has repeatedly shown himself to be aware, it is the economic challenges of his presidency – hangovers of those which Sadat never solved – which will define it.

Sadat and Sisi, and more importantly the times they live in, are different enough that it would be foolish to assume that the fortunes of the latter can be inferred from those of the former. But as Egyptians hope for a new Nasser, it’s worth remembering that they may be getting something a bit closer to a new Sadat.

Tom Dale is a freelance multimedia journalist based in Cairo. He has been reporting from Egypt and Libya since 2011. You can follow him on twitter at @tom_d_.

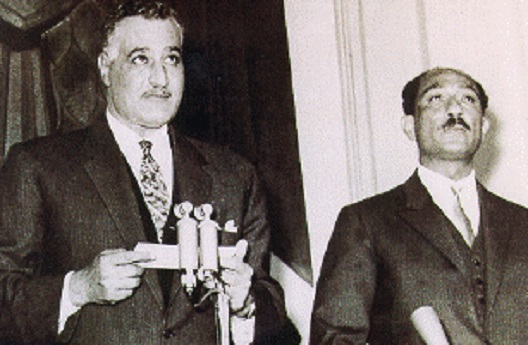

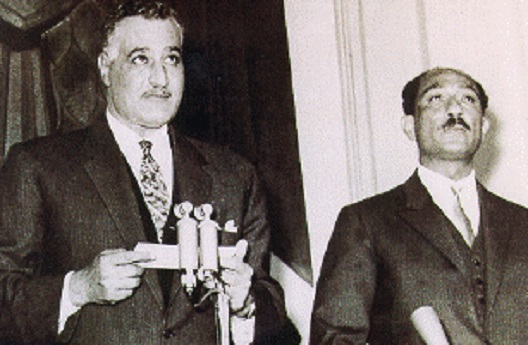

Image: Gamal Abdel Nasser delivers a speech as Anwar al-Sadat stands next to him. (Photo: Wordpress/Uprooted Palestinian)