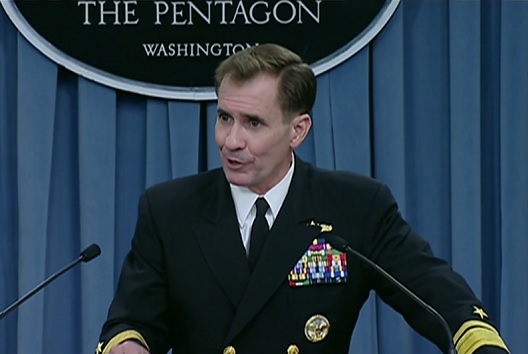

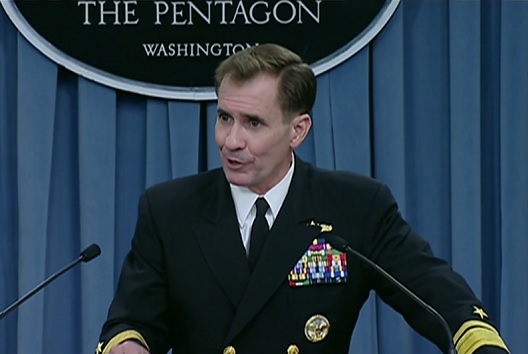

As matters now stand, the Obama administration sees the Syrian side of the anti-Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS, or the Islamic State) military campaign in the context of a headquarters/safe-haven for an enemy whose main target is Iraq. As Department of Defense Press Secretary Rear Admiral John Kirby put it on October 8, “In Syria, the purpose of the airstrikes largely is to get at this group’s ability to sustain itself, to resupply, to finance, to command and control. They use Syria as the sanctuary and safe haven so that they can operate in Iraq.” Can President Barack Obama achieve his objective of degrading and destroying ISIS with Syria regarded merely as a safe-haven and Bashar al-Assad as simply a bystander? He cannot.

As matters now stand, the Obama administration sees the Syrian side of the anti-Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS, or the Islamic State) military campaign in the context of a headquarters/safe-haven for an enemy whose main target is Iraq. As Department of Defense Press Secretary Rear Admiral John Kirby put it on October 8, “In Syria, the purpose of the airstrikes largely is to get at this group’s ability to sustain itself, to resupply, to finance, to command and control. They use Syria as the sanctuary and safe haven so that they can operate in Iraq.” Can President Barack Obama achieve his objective of degrading and destroying ISIS with Syria regarded merely as a safe-haven and Bashar al-Assad as simply a bystander? He cannot.

Yet the president’s approach to the problem seems to be one of treating the ISIS symptoms while allowing the underlying policy disease to persist. Rhetoric about supporting beleaguered Syrian nationalists being squeezed by ISIS and the Assad regime in tandem—even elevating them to the role of putative coalition ground combat component in Syria—is accompanied by nothing of substance. In his October 8 press conference, Admiral Kirby was refreshingly if depressingly frank. He cut through all of the State Department vacuity about supporting the moderate opposition: the Department of Defense sees no one with which it can cooperate on the ground in Syria; the process to be traversed before a single Syrian nationalist fighter is trained is at least three to five months. This is the policy equivalent of shooting blanks.

President Obama’s vigorous response to the ISIS threat and his decision to authorize airstrikes in Syria initially alarmed Iran, Russia, the regime, and regime apologists. None of those parties need have worried. None of the rhetorical sound and fury signifies a change in Syria policy.

The current policy is one that requires Admiral Kirby to say, “…we don’t have a force inside Syria that we can cooperate with and work with. That’s why we want to get this train-and-equip program up and running.” In fact, there is no reason not to draw on nationalist opposition forces in Syria to identify ISIS targets. But to make use of them in that manner might lead some in the administration to think that perhaps the United States ought to do something to protect them and their constituents from Assad regime barrel-bombs and artillery attacks. This is inadmissible. Therefore, pretend there is no one on the ground who can help, and kick the train-and-equip can down the road as far as possible. In the words of the Admiral, “There’s been no vetting started yet and no recruiting at this point… we are in the very early stages right now of trying to develop the procedures and protocols within which we would do that.” So much for taking a contingency plan off the shelf and executing it: the idea that the commander-in-chief might someday ask the Department of Defense to train and equip Syrian rebels must not have occurred to anyone.

Admiral Kirby did, however, reflect the administration’s rhetorical take on Syria accurately: “Nothing has changed about the desire by this government that Assad has lost all legitimacy and has to go. Nothing has changed about the fact that we believe… continue to believe that he’s a big part of the problem here. He is one of the reasons why this group has been able to grow and develop inside his country.” Assad is, in fact, the main reason ISIS was able to grow in Syria and sweep to the gates of Baghdad. He is, from the point of view of the self-anointed caliph, a gift that keeps on giving. Not only does he barrel-bomb those the caliph wants dead, but his addiction to war crimes and crimes against humanity—most committed in a flagrantly sectarian context—recruits fighters to the ISIS cause from all around the globe.

In the context of Iraq it was not difficult for adversaries—Washington and Tehran—to perceive the corrosive effects of Nouri al-Maliki on Iraqi unity. He too was a gift to the caliph. Washington no doubt, as Admiral Kirby suggests, sees Syria’s Assad in a similar light. There are even those in Tehran who recognize and regret the gratuitously murderous tactics of their client in Damascus. Yet Tehran is serious about coupling interests with action. Assad is an order-taker when it comes to Iran’s most important geopolitical asset in the Levant: Lebanon’s Hezbollah. Keeping Hezbollah in a position to menace Israel with rockets and missiles is what makes Bashar al-Assad essential to Tehran. The Islamic Republic is the soul of pragmatism: yes, Assad is essential to ISIS; but his value in terms of Hezbollah mandates his preservation.

If the core of the Obama administration’s objective with respect to Assad is that he has “lost all legitimacy and has to go,” what seems to be missing is a strategy to make it happen. Wishing and hoping for political transition negotiations to materialize is not a strategy. Dismissing the relevance of military developments on the ground in Syria with the mantra of “no military solution for Syria” is not a plan. Telling allies and friends—particularly Arab partners—to concentrate exclusively on ISIS while ignoring the principal cause of the ISIS phenomenon is not a persuasive argument.

The strategic vacuum is being filled, once again, by a nimble, cynical, and opportunistic Assad regime. Left free to engage in military air operations while coalition aircraft prowl the skies of Syria, regime aircraft hit residential areas near coalition targets in order to create two impressions for Syrians: that it is part of the coalition effort and that civilian casualties it creates are really the responsibility of the coalition. If the Obama administration feels outrage over being used thusly, it is concealing its anger admirably.

Is it beyond the wit and capacity of the United States to ground the Assad air force for the duration of the coalition’s anti-Assad air campaign? Is it impossible to see if the Turks mean business with their talk of establishing a political and humanitarian buffer zone within Syria? Is it unthinkable to bring the nationalist opposition into the tent for military planning? Is it logistically too heavy a lift to resupply nationalist fighters robustly? Is it politically and diplomatically beyond the pale to encourage the Syrian National Coalition and the Interim Government to deploy to Syria, link up with local committees, and begin to restore Syrian governance in the face of regime and ISIS criminality? Are all of these things just too hard to do for the United States of America?

ISIS is in the position it is in now partly because none of those things were done. It will stay in business so long as they remain undone. The objective—Assad out—has been clear since President Obama mandated it on August 18, 2011. But Syria, at least in terms of administration policy, remains a problem in search of a strategy.

Frederic C. Hof is a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

Image: Screenshot of RADM John Kirby's press briefing at the Pentagon. (Photo: US Dept. of Defense)