In a word: yes. Bashar al-Assad is absolutely crucial to defusing the conflict in Syria. United Nations Special Envoy Staffan de Mistura attracted considerable controversy and criticism for having stated the obvious. Assad, who has burned Syria to the ground rather than yield personal power via a political transition process, remains the key to any civilized denouement. De Mistura committed truth. He is taking considerable and unjustifiable heat for having done so.

In a word: yes. Bashar al-Assad is absolutely crucial to defusing the conflict in Syria. United Nations Special Envoy Staffan de Mistura attracted considerable controversy and criticism for having stated the obvious. Assad, who has burned Syria to the ground rather than yield personal power via a political transition process, remains the key to any civilized denouement. De Mistura committed truth. He is taking considerable and unjustifiable heat for having done so.

Critics of the special envoy seem to assume that de Mistura was endorsing a role for Assad in a transitional governing body; something consistent with Iranian and Russian suggestions that there would be value in an ongoing, if time-limited, role for Mr. Assad as President of the Syrian Arab Republic. Yet the special envoy also reaffirmed that the June 30, 2012 Geneva Final Communique remains the official, P5-endorsed framework for Syrian political transition.

That communique calls for a transitional governing body to be selected via opposition-regime negotiations governed by mutual consent. If the Syrian opposition wishes to accord Bashar al-Assad a role in the transitional governing body, it need only render its consent. De Mistura in no way preempted a right accorded to the Syrian opposition by Russia, China, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

The criticism of de Mistura appears reflexive in nature. His call for a freeze of all armed activities in and around Aleppo has been rebuffed by a regime that sees paltry assistance from the West to nationalist rebels as a green light to finish the job militarily.

Nevertheless, the Syrian opposition suspects the initiative itself potentially to be a regime Trojan Horse in the event Assad’s military operations fall short: the mother of all fake ceasefires amounting to a conditional surrender, with all conditions inevitably to be violated by the regime. This indeed has been the pattern of previous local ceasefires. The key to the actual utility of the Aleppo proposal would be the ability of the United Nations to put assets on the ground capable of guaranteeing the freeze/ceasefire terms. Otherwise, the regime would use the freeze to “disappear” nationalist fighters and insert its operatives into opposition neighborhoods.

It is deep suspicion of the motives, the wisdom underlying the Aleppo freeze proposal, and the feared consequences of the freeze going into effect that accounts for much of the negative reaction to the special envoy’s recent words about Assad’s centrality. Yet there is something else: the belief in opposition circles that any mention of Assad’s name outside the context of war crimes and crimes against humanity gives him political salience and status totally undeserved; that the regime takes to the bank any public uttering of Mr. Assad’s name that does not include a detailed citation of criminal conduct.

Given what the regime has done to Syria over the past nearly four years, such a reaction is understandable. Yet although it is unclear why Steffan de Mistura spoke publicly in the way he did—what actual mediating purpose may have been served by the statement—that which he said is beyond dispute in terms of fact. Were Bashar al-Assad to do the right thing—order his representatives to negotiate in good faith a transitional governing body and letting the mutual consent chips fall where they may—he would play a crucial role in defusing the conflict. Were he to implement former special envoy Kofi Annan’s six-point deescalatory proposal, he would play a crucial role in defusing the conflict. Were he and his key lieutenants simply to get on an airplane and leave for Iran, Russia, Belarus, Venezuela or wherever, he would play a crucial role in defusing the conflict.

Alas, there is no evidence that Assad has any interest in defusing anything except on his own terms. This is the principal obstacle faced by private groups engaging in discussions with regime-approved interlocutors. Even as some members of these groups articulate the willingness to toss the Geneva communique and all notions of transitional justice overboard in an effort to appease a rapacious regime, they see no evidence of flexibility on the part of the ruling family.

Steffan de Mistura spoke the truth: Bashar al-Assad is crucial to defusing the conflict in Syria. One can say just as truthfully that Vladimir Putin is crucial to defusing the conflict in Ukraine, or that Adolph Hitler was crucial to the fate of Europe in the late 1930s. What is important is not that de Mistura spoke the objective truth or that he was roundly criticized for doing so. What is important is that the Assad regime manifests no interest in defusing anything: a death sentence for Syria and a gift of unsurpassed value for the pseudo-caliph of the so-called Islamic State holding forth in a vast area encompassing large parts of Syria and Iraq.

Frederic C. Hof is a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

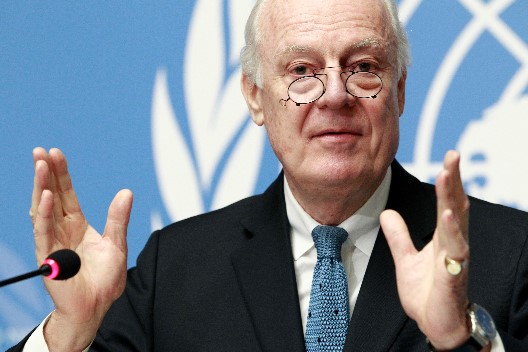

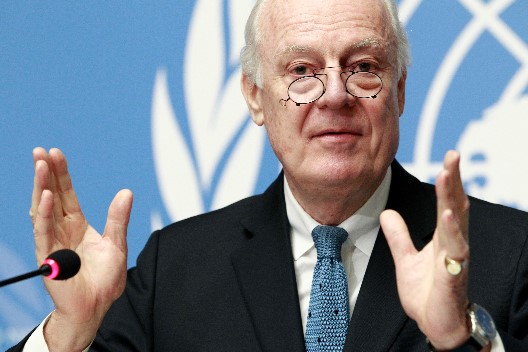

Image: United Nations Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Syria Staffan de Mistura addresses the media during a press conference at the Palais des Nations in Geneva, January 15, 2015. REUTERS/Pierre Albouy