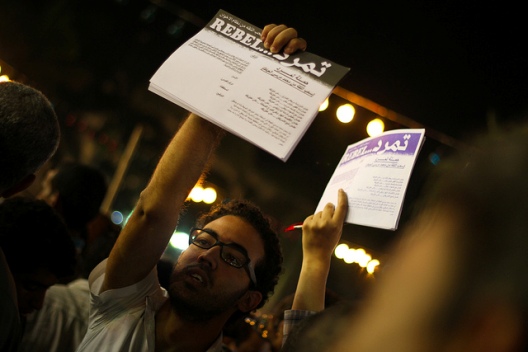

In late April, a group of unknown young Egyptian men announced the formation of a campaign against former Muslim Brotherhood president Mohamed Morsi and his regime. Today, that same group, Tamarod, or ‘Rebel,’ is one of the military-backed interim regime’s most ardent supporters.

In late April, a group of unknown young Egyptian men announced the formation of a campaign against former Muslim Brotherhood president Mohamed Morsi and his regime. Today, that same group, Tamarod, or ‘Rebel,’ is one of the military-backed interim regime’s most ardent supporters.

Tamarod was established in rebellion against the then-ruling regime, with the aim of collecting signatures from Egyptians to demonstrate a vote of no-confidence against Morsi. The initial demand for Morsi to call for early presidential elections quickly snowballed into calling for his immediate removal. Yet now, Tamarod stands against all those who question, let alone rebel against, the current interim regime, challenging its own name in the process.

The campaign’s support for the military-backed regime didn’t falter with the forcible dispersals of the pro-Morsi Raba’a al-Adaweya and al-Nahda sit-ins which left hundreds of civilians and dozens of security personnel dead. As security personnel violently dispersed the Raba’a sit-in on August 14, Tamarod spokesman Hassan Shahin told me the state was “only doing its duty in protecting Egyptians against the Muslim Brotherhood’s terrorism.” Shahin expressed his campaign’s sorrow for the loss of life, yet was quick to place the responsibility for the bloodshed on Morsi’s supporters. The same Shahin said in a press conference three months earlier, “The legitimacy of Morsi, stemming from the ballot boxes, has elapsed with the arrival of victims’ coffins.”

Right after the sit-ins’ dispersal, however, Tamarod leaders Mahmoud Badr and Mohamed Abdel Aziz surprised Egyptians with a televised national address on state television, calling on Egyptians to form neighborhood watches to protect homes, mosques and churches. In their statements, they adopted the government’s rhetoric of a fight against domestic terrorism. Addressing the nation on the highly regulated state-run television stations in the hallowed halls of Maspero is no easy matter. Clearly, Tamarod’s address was welcomed, if not invited, by authorities.

A shift in Tamarod’s attitude was not lost on all of its members, with collective resignations submitted by leaders and members of the group in Assiut and Beni Suef. They accused the Cairo branch of marginalizing other governorates, while others said that Tamarod had lived out its purpose. The Cairo-group has, however, been quite vocal in its criticism of all who oppose the roadmap Egypt currently finds itself on – whether former vice president Mohamed ElBaradei or even the US government.

The campaign is now considering launching its own political party. Campaign coordinator Mohamed Heikal told me Tamarod has “enough popularity” to form a party, adding that current situation in Egypt necessitates the campaign evolving into a party, and to compete in the coming parliamentary elections. Since then, Tamarod founder Mahmoud Badr has reiterated that position, telling Kuwaiti newspaper al-Watan that he did not want the group to meet the same fate as the Brotherhood, by operating outside of the law.

Tamarod’s popularity in the wake of Morsi’s removal is, however, questionable. Like the January 25 movement, many of the signatories of the petition may have moved on to personal or narrower interests, having achieved the common goal of ousting Morsi. While Tamarod has announced a new initiative, aiming to encourage Egyptians to participate in the amending of the 2012 constitution, the campaign has made little traction in comparison to the group’s first petition movement.

In 2011, in the wake of former President Hosni Mubarak’s ouster, the April 6 Movement enjoyed similar levels of popularity as Tamarod. The former, however, never claimed leadership of the January 25 movement. While encouraged to establish a party and play an active part in politics, April 6 declined. At the time, the group said Egypt doesn’t need another political party, although it remains in dire need of an active movement, close to the streets, to keep monitoring the authorities.

April 6’s popularity was soon shaken in 2011, as the military regime launched a smear campaign tarnishing its image, alongside another key movement that galvanized street protests in the Mubarak era – Kefaya. Members of the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) suggested April 6, and others, received foreign funding from countries eager to see Mubarak’s regime toppled.

The January 25 Revolution was both highly criticized and applauded for its lack of any clear leadership. This lack of leadership secured the revolution against back-room deals, but at the same time, placed the supporters of January 25 one step behind those willing to negotiate with the then-ruling military. In contrast, since June 30, whenever the powers that be want to demonstrate they are working hand-in-hand with the ‘revolution,’ Tamarod is always invited to the table.

This has led to Tamarod becoming the only group with multiple representatives in the constituent assembly tasked with amending the 2012 constitution. Mahmoud Badr and Mohamed Abdel Aziz were both named as part of the constituent assembly, likely as an attempt to consolidate the body’s appearance of revolutionary legitimacy.

Judging by Tamarod’s public position, it is safe to say, however, that the campaign has been taking an active role in the military’s propaganda in a way that is neither “revolutionary” nor “rebellious.” The campaign is also openly competing for power, and is not embarrassed to pursue that quest hand-in-hand with the military.

Campaign members constantly argue that they cannot help but support the army, saying it is the army that saved the country from the grave danger that is the Muslim Brotherhood’s rule. They, therefore, see no reason to hide their appreciation and respect for the patriotic institution. Their arguments are, to some degree, fair. Yet, the fact that they see only the army’s “achievements” and choose to turn a blind eye to the numerous violations practiced by the military backed regime is anything but fair.

In truth, Tamarod seems to be more like the Muslim Brotherhood they revolted against. Two years ago, the Brotherhood chose to side with the military, and sell out the January 25 revolution in exchange for personal gains. Tamarod appears to have set itself on a similar path, claiming ownership of the revolution, and reaping its rewards.

Rana Muhammad Taha is a journalist working for the Daily News Egypt.

Image: Photo: Bora S. Kamel