Egypt’s oldest nationalist party, the Wafd Party, is facing a deep and challenging internal conflict. Despite intervention by Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, a new internal election, and a formal announcement that the crisis is over, the party’s internal problems are unlikely to heal soon.

Egypt’s oldest nationalist party, the Wafd Party, is facing a deep and challenging internal conflict. Despite intervention by Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, a new internal election, and a formal announcement that the crisis is over, the party’s internal problems are unlikely to heal soon.

On the surface, the party appears to be divided between two camps. The first is led by party leader El-Sayid El-Badawy, while the second supports leading member, Fouad Badrawy, who hails from a family with strong Wafd roots.

Badrawy lost by a small margin in the party’s leadership elections in April, 2014. He received 956 of the votes, while current leader, Badawy, received 1,183. Earlier this month, following a decision by over 1,000 members to withdraw confidence in Badawy, the current leadership suspended Badrawy and seven other members of the party’s high board. Together the suspended members refer to themselves as the Wafd’s Reform Front. Following Sisi’s intervention, an agreement was apparently reached among party members to reinstate the suspended members.

However, beneath the party’s internal bickering lie more serious problems for the Wafd. The party, which has survived decades of turbulent Egyptian politics, has a long record of grave errors of judgment. For this, it is now paying a hefty price.

The Beginnings of the Wafd

The founder of Wafd, Saad Zaghloul, was not just an Egyptian national hero; he represented the aspirations of many Egyptians to have a contemporary, independent state that values all its citizens regardless of religion, ethnicity, class, or gender. That is precisely why, in the 1919 uprising against the British, Egyptians chanted “Saad! Long live Saad!” For them, he was the humble Egyptian citizen who understood the poor, and at the same time, the Pasha who fit in with the aristocracy. Zaghloul’s ability to manage this delicate balance was crucial for his success and for the popularity of his party, which continued after his death under the leadership of his successor, Mustafa al-Nahas. Even after Gamal Abdel Nasser disbanded all political parties in 1954, Egyptians did not forget Wafd and its positive role in Egypt’s contemporary evolution.

Later, following Nasser’s death, the Wafd Party was briefly resurrected during Sadat’s rule, then later during Mubarak’s tenure. The revival of the Wafd triggered some optimism regarding shift from an authoritarian political scene to a pluralistic democracy. I remember how residents of Heliopolis in Cairo warmly received famous composer and Wafd member Kamal al-Taweel when he decided to run for parliament in the late eighties. Many eager voters hoped the elegant, talented composer, whose music captivated millions in Egypt, would bring with his party a new air of elegance to Egypt’s rotting political life.

The high expectations, however, failed to materialize. Instead of revitalizing Egypt’s democracy, or at least pushing Mubarak’s regime out of its comfort zone, the Wafd opted to maintain the status quo, accepting the role of a “decorative opposition” that legitimized rather than discredited the regime. During the 2005 presidential elections, the Wafd’s Noaman Gomaa ran for president alongside Mubarak and Ayman Nour, despite a boycott by other parties. This in turn legitimized the outcome in favor of Mubarak. Gomaa’s poor performance in the presidential election, together with an equally poor party performance in the parliamentary elections, created serious divisions within the party.

Policies of Convenience

Since its creation, the Wafd has shifted its stances on several issues, including religion. In the lead up to the 1984 parliamentary elections, the Muslim Brotherhood and Wafd formed an electoral coalition in an attempt to counterbalance the dominance of the then-ruling National Democratic Party. The two groups managed to win fifty-eight seats in the 458-member parliament. The “new” Wafd put aside its famous slogan “Egypt is for Egyptians, and religion is for God” and adopted a more Sharia-compliant rhetoric in order to survive the rise of political Islam and the Brotherhood’s own slogan “Islam is the solution.” Unsurprisingly, the alliance fell apart after the election. Later, however, in 2010, cooperation between the two groups became more visible, again prompting more internal divisions among party members.

The Wafd also distanced itself from its policy of tolerance, embracing a more anti-Semitic view. As Samuel Tadros points out, Ahmed Ezz al-Arab, the vice chairman of Wafd, openly denied the Holocaust in a 2011 interview with The Washington Times. The only possible explanation for this view is again due to the party’s desperate desire to fit in with the prevailing climate in Egypt that has grown hostile to Jews since Egypt’s 1967 defeat against Israel. Recently, commenting on Norway’s objection to deposed President Mohamed Morsi’s death sentence, Ezz al-Arab compared it to Norway’s execution of Vidkun Quisling, a Norwegian politician who aided Hitler’s occupation of Norway. These deeply illiberal remarks do not reflect Ezz al-Arab alone. The fact that he secured a top rank in the party latest’s High board election, receiving 1,218 votes, indicates that many in the Wafd share his alarming, illiberal views.

During the 2011 revolution, the Wafd, like the Muslim Brotherhood, did not initially join the demonstrations; however, party leader Badawy gave his approval for the youth of his party to participate in their personal capacity. This sit-on-the-fence attitude symbolized his leadership style that neither inspired popularity nor earned the party any revolutionary credentials.

In 2013, the Wafd Party supported Sisi’s roadmap after Morsi’s ouster, but the party leader later lashed out after a meeting with Prime Minister Ibrahim Mahlab regarding the electoral law for the upcoming parliamentary election. Badawy said that the next parliament would be the “worst in Egypt’s history.”

The Egyptian Wafd

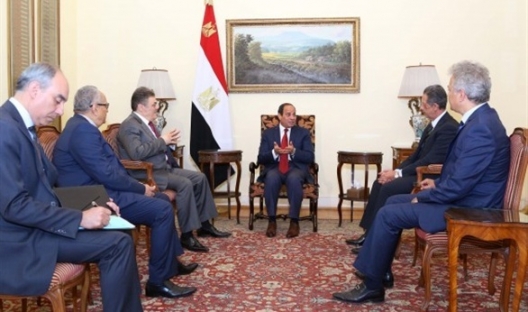

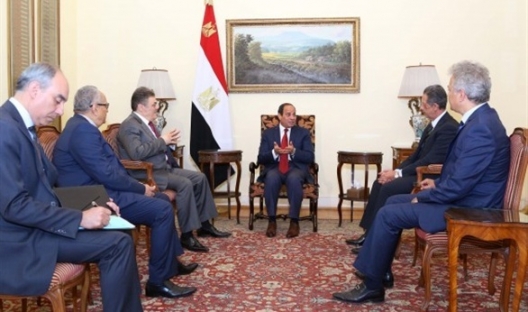

Despite those fiery comments, Wafd’s leadership welcomed Sisi’s intervention following its recent internal rift. A senior member described it as “a lifejacket” for the party. This description provides the best explanation of the relationship between the president and non-Islamist political parties in Egypt. On the one hand, they need him as a patron who conceals their own unpopularity. On the other, Sisi needs parties that compete in the parliamentary election ___ the crucial, final part of his pledged roadmap. Sisi cannot afford for Egypt’s oldest party, the Wafd, to suffer an internal meltdown.

Now the Wafd has a new elected board, which has voted in favor of a bylaw amendment to change the name of the party from “New Wafd” to its original “Egyptian Wafd.” Will this change signal a return to the party’s original values? Unlikely.

Sadly for the Wafd, it is relying heavily on the grandeur of its past, rather than its present achievements – on the old Egyptian Wafd, which was led by true statesmen who stood by their principals. The Wafd Party has shifted from the party that campaigned for freedom to a shallow, go-with-the-flow party that is willing to accommodate everything from authoritarianism and revolution to Islamism and a coup, with survival as its sole aim. The Wafd also suffers from a deep identity crisis. It has become neither liberal nor secular, and enjoys no distinct differences that make it stand out among other non-Islamist Egyptian parties.

In 1965, during the funeral of Wafd’s late leader, Mustafa al-Nahhas, thousands of Egyptians chanted during the funeral procession: “There is no leader after you Nahhas.” With the current colorless, divisive leadership of Wafd, that prediction has tragically proven to be correct.

Nervana Mahmoud is doctor, blogger and a writer. you can follow her on Twitter : @Nervana_1

Image: Photo: President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi meets with Wafd Party leaders (Egypt Presidency)