Marcel Kurpershoek served as the Netherlands’ Special Envoy to Syria from August 2013 through December 2014. Ambassador Kurpershoek is a well-respected Dutch Arabist, and was ambassador for the Netherlands in Poland, Turkey, Pakistan and Afghanistan. He also served as a diplomat in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Syria. Before leaving his post as envoy, Kurpershoek delivered remarks on the crisis in Syria to an audience at Casa Árabe, a Spanish public consortium headed by Spain’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation that serves as a strategic center for Spain’s relations with the Arab world. A version of his remarks were published in Dutch in the NRC newspaper on January 3, 2015. Below is the English translation.

Marcel Kurpershoek served as the Netherlands’ Special Envoy to Syria from August 2013 through December 2014. Ambassador Kurpershoek is a well-respected Dutch Arabist, and was ambassador for the Netherlands in Poland, Turkey, Pakistan and Afghanistan. He also served as a diplomat in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Syria. Before leaving his post as envoy, Kurpershoek delivered remarks on the crisis in Syria to an audience at Casa Árabe, a Spanish public consortium headed by Spain’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation that serves as a strategic center for Spain’s relations with the Arab world. A version of his remarks were published in Dutch in the NRC newspaper on January 3, 2015. Below is the English translation.

As the international community grappled in 2014 with resolving the Syrian crisis, two statements by US Secretary of State John Kerry stuck with me. At the outset of the Geneva II meetings—the failed Syrian peace talks held last February in Switzerland—Kerry stated flatly, “When the Assad regime speaks about leading the fight against terrorism, the fact is that Assad himself is the biggest magnet for terrorism in the world.” One month earlier, at the UN donors’ conference in Kuwait, he had said, “It cannot be that one year from now we shall stand here again having to pledge billions because of an unresolved political crisis.”

These two sentences spoken by Kerry were right on target and should have guided the international community in its approach to Syria. Unfortunately, that has not been the case. A year has passed and not only has the cost of the humanitarian crisis increased, there is the added cost of the air campaign against the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS or ISIL). In spite of great efforts by previous UN envoys, and now Staffan de Mistura, we are still waiting for real flexibility to address the political causes of the conflict.

Today, those who argue that President Bashar al-Assad is the “lesser evil” seem to have gained traction. They are, of course, presenting a false choice. No one of sound mind would prefer the so-called Caliph of ISIS, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, leading prayers at the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, yet that does not mean we should invite Assad and his army to join the coalition against ISIS.

The arguments against collaborating with the Assad regime are practical as well as moral.

In practical terms, it is dubious that the Assad regime could serve as a reliable, capable military partner. And, considering the outlook of most nations in the anti-ISIS coalition, any move to partner with Assad would come at the cost of dissolving the coalition. Thus, the military net gain is questionable.

Moral considerations rule out the possibility of rapprochement—Assad is beyond rehabilitation. Never mind that many of his war crimes are committed in secret, while ISIS puts theirs on YouTube. Assad’s crimes are well known—if one has the fortitude to examine the horrible stories of detention, torture, rape, starvation sieges, and general disregard of the Geneva Conventions through indiscriminate razing of entire cities.

Setting aside the above considerations, taking the “lesser evil” approach would mean walking with open eyes into the trap that Assad and his mentors laid in Geneva and before. They insisted that the uprising has no popular basis, but was a foreign plot led by jihadists determined to extend their puritanical vision through violence.

This is a blatant misrepresentation of history, but Assad certainly did his best to make it true. Perhaps he thought that these bogeymen would help him justify opening fire on peaceful demonstrators. His father, Hafez al-Assad, set the example in the early 1980s when a Muslim Brotherhood uprising was put down with massive violence. At the time, I served at the Dutch embassy in Damascus and was admonished to focus squarely on the Syrian role in Lebanon and possible openings for Syria joining the peace process with Israel—how the dictator treated his own people was a lesser concern. We should not make the same mistake now: missing the Syrian-Iraqi forest for the ISIS trees.

Then, as now, the easiest and surest way for the Assad regime to seek sympathy in the West was to brand any Sunni political mobilization as a terrorist plot. Might this stratagem work again thanks to ISIS? Clearly, the Assad regime is betting on that.

We should not join Assad in seeing ISIS as the root problem in Syria. Yes, ISIS should be destroyed, but counterterrorism tools alone are not a long-term strategy to stabilize Syria. Sustainable stability will not arrive without an agreed process for Assad to step down. The alternative is continued destruction, and further rise of extremist factions.

A stopgap solution, like former Iraqi Prime Minister Maliki relinquishing power, is not ideal, but could be an important step towards stabilization followed by real dialogue. This will be a long and difficult process that requires constant pressure from the international community.

There can be no collaboration with this dictator who is at war with a major part of his country’s population. Another starvation siege in Aleppo, as in Homs, cannot be tolerated. The daily bombing of his own cities and people by the air force is in itself clear proof of the regime’s moral and political bankruptcy. Here is a clear parallel with Iraq’s Saddam Hussein who also thought gassing his opponents the cheapest and most effective way. So far, Assad was lucky to get away with handing over the criminal instruments—the chemical weapons—as a ransom for his continued political life.

Before her disappearance, the brave and passionate activist Razan Zaitouneh, wrote: “Syrians will not forget that the international community forced the regime to dismantle its chemical weapons, yet could not force it to break the siege on a city where children are dying of hunger on a daily basis.” Kidnapped in December of 2013 by masked gunmen, Zaitouneh’s whereabouts are unknown. But with Assad at the helm, there can be no future for the Syria that Zaitouneh aspired to, as a unified, pluralistic country.

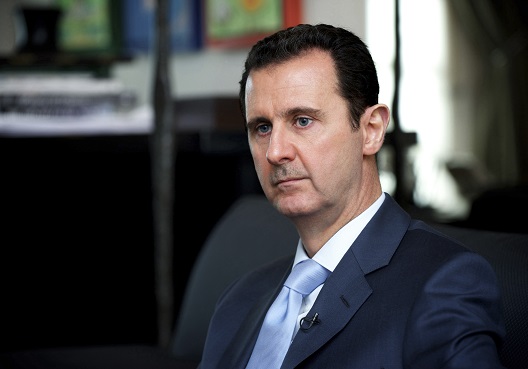

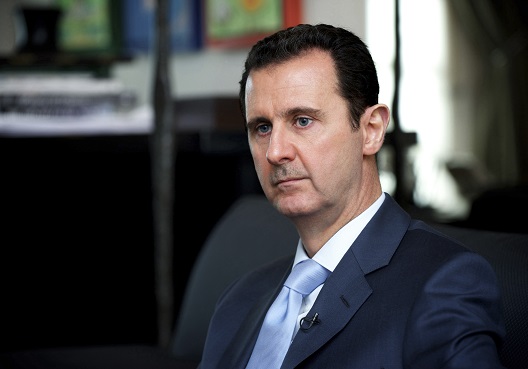

Image: Syria's President Bashar al-Assad is seen during an interview in Damascus with the magazine, Literarni Noviny newspaper, in this handout picture taken January 8, 2015 by Syria's national news agency SANA. (Photo: Reuters/SANA)