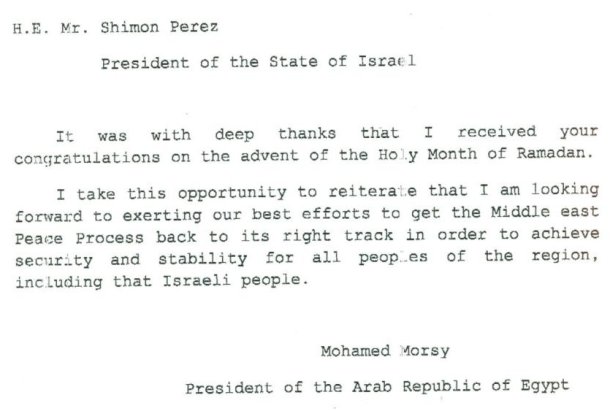

The debate over a letter allegedly sent to President Shimon Peres of Israel from President Mohamed Morsi has recently emerged as one of the more frustrating discussions to receive media attention. Journalists have traced the letter’s path from a fax machine at the Egyptian embassy in Tel Aviv to the Israeli President’s office, published confirmation of receipt from the Israelis, but vehement denials from Cairo and the Muslim Brotherhood. The Egyptian Foreign Ministry remained silent. Some commentators labeled the confusion over the letter as emblematic of the tenuous relationship between Israel and Egypt’s new Islamist government, and an atmosphere of disarray in Egypt’s diplomatic corp. Although most might focus on the former, the latter has farther reaching implications and speaks to a level of confusion within President Morsi himself.

The Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt has built itself up (in part) over its hostility to Israel, allowing it to gain traction among a population that remembers fighting wars with its Jewish neighbors and sympathizes with Palestinians suffering under occupation. For anyone raised in Egypt, it also taps into something subtle and visceral: the historical antagonism between Jews and Muslims during the founding of Islam as taught in schools across the country. Mubarak’s cold but cooperative relations with Israel received much criticism from Brotherhood members, often used as a political barb from the then-opposition to counter the regime. Coming from that paradigm, how could such a cordial letter thanking Peres for his Ramadan well-wishes and urging the resumption of a Mideast peace process possibly be sent from President Morsi himself? Except for one thing: the president is no longer a member of the Muslim Brotherhood… or is he?

There can only be three possibilities to this story:

1. A rogue instigator “fabricated” the letter to create a diplomatic kerfuffle.

2. A member of the Egyptian diplomatic corps responded on President Morsi’s behalf.

3. Morsi ordered the letter written, or wrote it himself, but later denied sending it.

While conspiracy theorists would love to latch onto possibility #1, the other two remain the most likely culprits. If one takes President Morsi at his word, possibility #2 highlights a level of miscommunication within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that at worst is disconcerting, but not catastrophic. One can understand that, in the midst of a cabinet reshuffle and a highly dynamic political environment, certain details may fall through the cracks (as unlikely as that may be in Egypt-Israel relations). Were the issue more serious than a courteous reply, one could imagine a potential fiasco – but this incident certainly isn’t cause for concern.

The last possibility is the most likely, and truly the most troubling. It goes without saying that a president is expected to maintain diplomatic relations with those countries where interests directly cross paths, regardless of personal feelings. Much like the difference between campaigning and holding office, political realities will drive behavior that seems contrary to past positions. The day Mohamed Morsi became President Morsi, he resigned from the Muslim Brotherhood in an effort to “represent all Egyptians” and convince the public that his actions remain independent of any previous affiliation. If one assumes he did indeed write the letter, his spokesman’s adamant denial that he ever wrote a response to an ordinary diplomatic communiqué reflects a disturbing conflict within Morsi. It portrays a man unsure of his position, whether as an objective statesman or an extension of the Muslim Brotherhood in the office of the executive.

Whatever the truth behind a debate as asinine as this, President Morsi can no longer afford the luxury of

campaigner/administrator of or for the Muslim Brotherhood. His responsibilities transcend old tactics played out during the Mubarak era. The bottom line is that he must choose his legacy as the first post-revolution leader of Egypt. This story may end up as a mere blip on the political radar, but a statesman would have taken responsibility as a representative of Egyptian interests, whether he wrote the letter or not. That he insisted on denial does not bode well with regard to perceptions of his independence as a representative of the people.

Tarek Radwan is associate director for research at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East and a blogger for EgyptSource.

Image: letter.jpg