In 2009, the US Ambassador to Tunisia wrote in a cable later published by Wikileaks, “Tunisia is a police state,” where the ruling regime used the police to protect itself rather than citizens. Although they were merely the blunt end of an authoritarian system that extended into all sectors of economic, bureaucratic, and social life, police officers played a key role in maintaining a system of fear and control. Their disciplinary tactics relied heavily on violence, including killing and torture, as well as surveillance. The surveillance capacities of the police—its digital surveillance in particular—should not be underestimated. There is little evidence to show that leadership structures, investigative practices, or the laws governing the security forces have changed since the revolution in 2011. Until the Tunisian government has the political will to undertake difficult structural reform in the country’s security sector, the police will continue to enjoy the kind of impunity that contributed to civil unrest not so long ago.

In 2009, the US Ambassador to Tunisia wrote in a cable later published by Wikileaks, “Tunisia is a police state,” where the ruling regime used the police to protect itself rather than citizens. Although they were merely the blunt end of an authoritarian system that extended into all sectors of economic, bureaucratic, and social life, police officers played a key role in maintaining a system of fear and control. Their disciplinary tactics relied heavily on violence, including killing and torture, as well as surveillance. The surveillance capacities of the police—its digital surveillance in particular—should not be underestimated. There is little evidence to show that leadership structures, investigative practices, or the laws governing the security forces have changed since the revolution in 2011. Until the Tunisian government has the political will to undertake difficult structural reform in the country’s security sector, the police will continue to enjoy the kind of impunity that contributed to civil unrest not so long ago.

After the 2011 uprising, fifty-eight defendants, including former president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, were accused of causing the deaths of protesters. Ben Ali received a life-sentence in absentia, but numerous top security officials received lengthy sentences that were subsequently reduced to three years by a closed military tribunal. Those officials now roam free, along with dozens of others who were simply acquitted from the outset. In numerous interviews over the years, protesters injured during the uprising and the families of “martyrs of the revolution” have said that this lack of justice (extensively documented by Human Rights Watch) is not only infuriating but also dehumanizing. Police violence against protesters has continued since 2011. The police have used birdshot, beatings, and possibly live ammunition to disperse public demonstrations on numerous occasions. In some cases, police violence has resulted in civilian casualties and torture remains endemic in police detention.

One may link the lack of accountability for those in leadership positions and insufficient scrutiny of operating practice to a legal framework that preserves the police state. Although Tunisia passed a largely progressive new constitution early last year, specific laws have not yet changed to reflect the principles inscribed in the new document. Two sets of legal text appear to reinforce an authoritarian-style function for the security forces: the terrorism law and the penal code. The Terrorism Law of 2003 passed under Ben Ali defined terrorism so broadly as to include “disturbing the public order.” Former UN special rapporteur on human rights and terrorism Martin Scheinin said the law was “widely abused as a tool of oppression against any form of political dissent.”

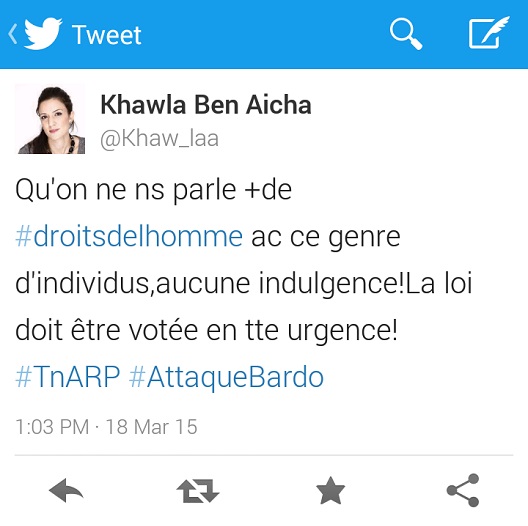

Since the uprising, some legislators have tried to reform this law, but new proposals still contain overly broad definitions of terrorism. Coincidentally, particularly heinous terrorist attacks have occurred just as legislators debate the issue. Delegates from the previous interim legislative body, the National Constituent Assembly, began discussing amending the 2003 law in the summer of 2014, just before gunmen attacked a group of Tunisian soldiers near Mount Chaambi, killing fourteen. Just one day before the Bardo attack, a parliamentary committee met with a representative from the ministry of interior to discuss terrorism in a closed session. At least one legislator had connected the Bardo attack to terrorism legislation, tweeting only hours after the incident, “Don’t talk to us anymore about human rights; with these types of individuals, no leniency! The law should be voted upon with all urgency!”

The penal code also overly empowers the security services’ repressive behavior. It outlaws insulting public officials—a text that has been used on numerous occasions to jail those who insult the police. After the uprisings, this has largely targeted artists and activists, but in its most recent application, has also been used to arrest two media personalities for offending the president.

That security forces still behave as they did under Ben Ali’s police state structure means that their function within the state is still largely one of disciplining subjects rather than protecting citizens from crime or terrorism. Weber defines the state as one that claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory. In that sense, the state itself was rejected, or at least contested, during the 2011 uprising. Protesters called for freedom, dignity, and work—in other words, citizenship. Many towns threw out their Ministry of Interior-appointed governors and some tried to install their own local chiefs. Tensions between citizens and state forces were at their worst in poor towns in the interior, like Kasserine and Sidi Bouzid, where the uprising first started.

On the first anniversary of the uprising, locals in Sidi Bouzid showed me the parts of town where security forces were still too scared to venture. The uprising had not only thrown off the yoke of fear, but had allowed locals to reclaim space from a state that had treated them as subjects, sources of rent, or merely targets of abuse. Locals had emerged as citizens, demanding the rights that accompany citizenship and a say in their governance. However, since then, power has shifted back to the state as security forces gradually reassert their presence in public spaces and commerce. A shift in the public discourse from one of citizenship and rights to one of national security and protecting the “prestige of the state” has helped the resurgence.

Media coverage, saturated with stories about the existential threat of terrorism, has spearheaded this security-centric narrative. Anyone who has travelled by plane from chaotic Libya to relatively tranquil Tunisia over the last few years would have laughed at the local newspapers, full of dire warnings, terror, and death. But yellow journalism is just one indicator of how language is an arena for competition between security forces and citizens. Political speech has also reflected this shift in discourse.

Tunisia’s anti-Islamist politicians have enthusiastically embraced a security-oriented perspective for political gain. In November’s election, now President Beji Caid Essebsi said that his opponent’s supporters included Salafi jihadists. A few days after Essesbsi’s victory, at a politically charged trial of a police union chief for defaming the military, a human rights advocate in Tunis reported a telling incident. According to the activist, a representative from the police union supporting his colleague on trial shouted, “There are no martyrs of the revolution. Do not say anymore that there are martyrs. They are all burglars, thieves. The only martyrs of this country are the security services and the army.”

The activist said, “The will to turn the page and rewrite the history of this revolution—misrepresenting it and dirtying it—is well and truly there, and it is gaining ground.” Tunisia’s exposure to unrest in Libya and extremism (to a lesser extent) internally has produced real security issues that require the service and protection of state security forces. Yet, without a balance between citizenship and security, Tunisia would risk a return to those same practices that sparked a revolution.

Fadil Aliriza is a journalist and analyst who was based in Tunis for several years after the uprising; he is currently a pursuing a master’s degree in Middle East politics at SOAS, University of London. Follow him on twitter @FadilAliriza

Image: A policeman stands guard outside the Bardo museum in Tunis April 8, 2015. (Reuters)