¡Viva los Arabes!: Underreported stories of the Arabs of the Americas

During a trip as a graduate student to As-Suwayda, Syria in the early 1990s, Dr. Sarah Gualtieri overheard Spanish—a language she was surprised to hear in the region. While in a café catching up with her friend, Dr. Guiltieri thought it was probably just Spanish tourists, but her friend corrected her and said that the “tourists” were Venezuelan-born Syrians visiting for the season.

Dubbed “Little Venezuela,” the southern town of As-Suwayda is known for its Hispanic influence from generations of Syrians who left in the nineteenth and twentieth century for Latin America. They did so for various reasons, including fleeing the Ottoman Empire after World War I and food shortages. Rediscovering their heritage, these émigrés had started to return either permanently or for the holiday season.

“A lot of the ways in which stories of Arab Americans are told is very standard, ‘Well, they came, like so many other immigrants did, to Ellis Island, they congregated in New York and they spread out to other areas, principally in the East Coast and Midwest,’” explained Dr. Gualtieri, now a professor of American Studies and Ethnicity, History, and Middle East Studies at the University of Southern California.

With countries like Syria in a civil war and Lebanon in an ongoing crisis, a lot of these émigrés—especially coming from places also in crisis, such as Venezuela—have found often themselves not returning to their ancestral lands. However, many have landed in the United States to reunite with family members who had already migrated to the US instead of Latin America in the twentieth century. This type of migration to the US has certainly not been the standard among Arab Americans and those of mixed heritage, and it is perhaps more of a recent phenomenon.

“How does that even happen?”

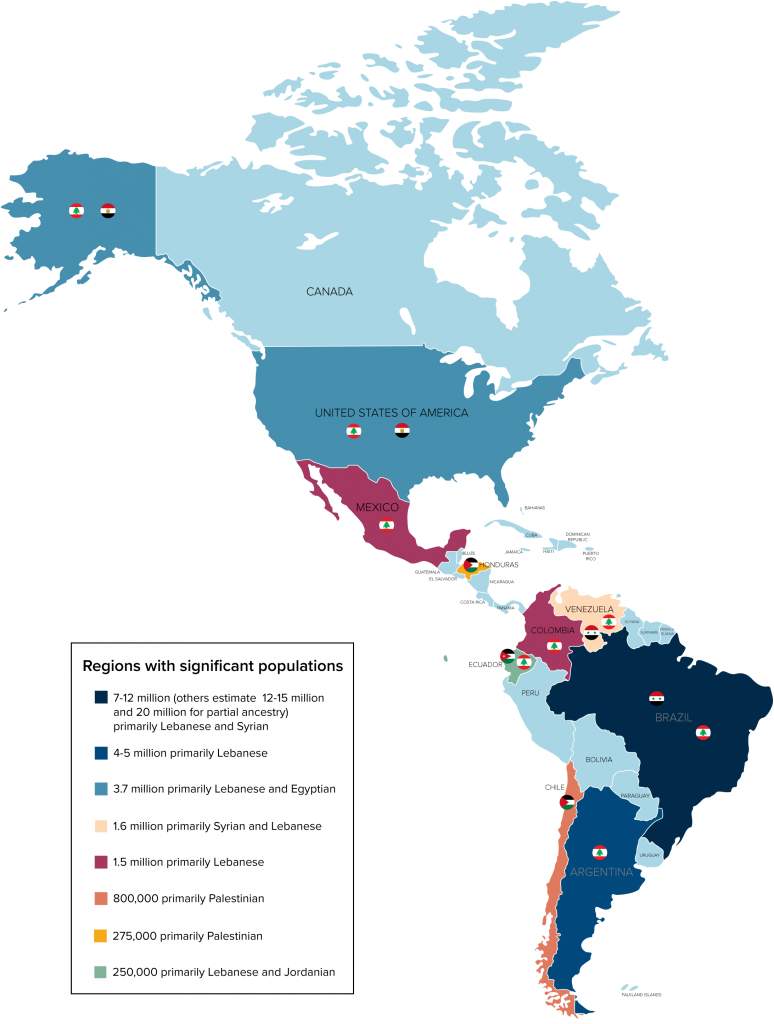

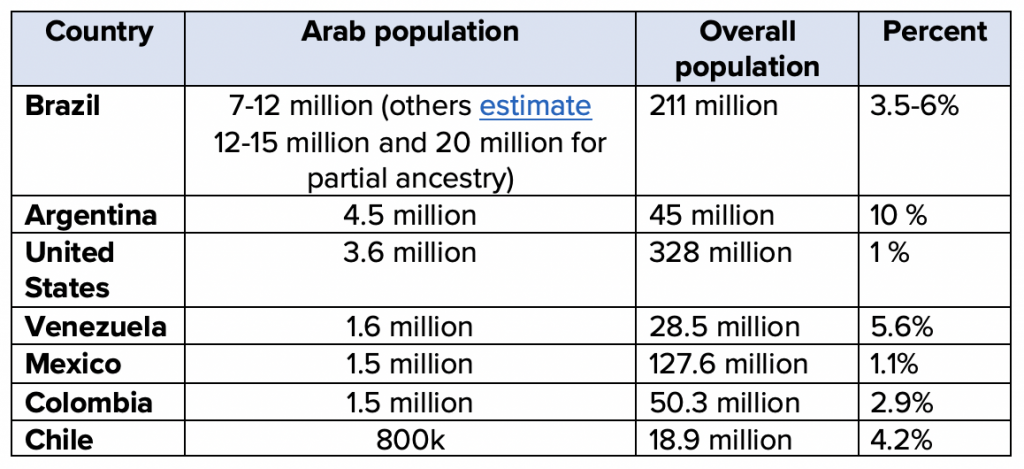

This is the startling question I often get, when mentioning the large migration of Arabs—including parts of my family from Lebanon as well as friends and neighbors—to the southern hemisphere. In fact, Dr. Waïl Hassan, director of the Center for South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Illinois, places Latin America as the host of the largest number of Arabs and their descendants outside of the Middle East, with estimates ranging from seventeen to thirty million descendants. Is it because of America’s obsession with race and group classifications that many cannot comprehend that Latinos can also be Arabs, and that these two do not cancel each other out? Or is it because Americans have mostly been told only one history of immigration since primary school? In any case, the question is always hard to answer without giving a passionate history lesson.

When the 2020 Superbowl happened, many on social media had never been exposed to such ethnic mixes. They were astonished and wondering why Colombian singer Shakira had belly danced or done that “weird thing with her tongue”—aka the zagrouta, a long, high-pitched vocal sound produced by a rapid back and forth movement of the tongue. The comments were probably because most of them had no idea that the multi-Grammy award-winning singer was actually part Arab—of a Lebanese father and Colombian mother—and was paying homage to her heritage. The performance was welcomed with fervor in the Arab American community and an explosion of memes. Shakira’s impact was, of course, massive. It led to many discussions on cultural diversity and the various cultures that have made America the place it is today. After all, Shakira was the first Arab Latina born in Colombia performing at the Super Bowl.

When did significant numbers start to migrate?

Migration in large numbers to Latin America started in the twentieth century with significant amounts of Arab Christians, but also Jews and Muslims fleeing the Ottoman Empire—what is now Syria, Lebanon, and Israel/Palestine. While many left after World War I and due to food shortages, some also departed due to population growth and the decline of the Silk industry in Mount Lebanon, given the rise of much cheaper and readily available Chinese and Japanese silk to European buyers.

Sources include: Arabs and the Americas: A Multilingual and Multigenerational Legacy (2019) by Wail S. Hassan; Arab Regionalism: A Post-Structural Perspective (2015)by Silvia Ferabolli; Arab America; Confederación de Entidades Argentino Árabes (Fearab); Marc Margolis, “Abdel el-Zabayar: From Parliament to the Frontlines,” The Daily Beast, 2017; “Las mil y una historias,” Semana; The Arab American Institute; US Census Bureau 2019 American Community Survey.

More recently, Palestinians who were left dispossessed in 1948 following the interstate war after the creation of the State of Israel fled and the Lebanese Civil War of 1975-1990 caused an exodus of people. In the twenty-first century, Syrian refugees have been the primary migrators. The exact numbers of émigrés remain unclear, as the integration quickly outpaced that of the same communities in the US, thanks to fewer restrictions and greater economic opportunities. Due to the Iberian legacy (Al-Andalus)—Spain and Portugal bringing to the Americas a culture that was prominently shaped by eight hundred years of Arabs, Moors, and Muslims living in the Iberian Peninsula—it is argued that Arabs who migrated to Latin America felt much closer to home than those who migrated to the US.

Integration differs in the US because many immigrants to Latin America were either Christian or converted to Christianity, including Orthodox and Catholicism. Yet, the Muslim community was also significant—going against the myth that most were Christians. The exception is maybe Chile, whose Arab population is mostly Orthodox—contrary to Brazil’s and Argentina’s, which were Lebanese Maronites. Many Arabs also Latinized their names and the majority completely dropped Arabic due to prejudices. Despite being seen as non-Europeans, they were seen as higher up in the Spanish-Portuguese caste or colorist system than other communities. Many, if not most, intermarried with the locals.

What was upsetting for most Arabs in Latin America, however, is that they are still wrongly referred to as “Turcos” or “Turks” by the average local since they migrated with passports from the Ottoman Empire, which used to rule their regions. Thus, the use of “Turks” did not fit any racial categories back then and is merely a tag and a bad habit that has stuck until this day.

Race, ethnicity, and visibility

According to the book, Race and Arab Americans Before and After 9/11, edited by Amaney Jamal and Nadine Naber, most Arab American writers used the trope “invisibility” to describe the place of Arabs within US discourse of ethnicity and race, including the government definitions that classify Arab Americans as “white.” While US popular discourse tends to represent Arabs as the “other” or different to whites, some scholars have argued that this was especially the case after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, which consolidated the nonwhite “otherness” (including in Latin America).

On the other hand, it is argued that counterparts in Brazil and Argentina have been “remarkably visible and successful” as cultural figures; businessman Carlos Slim presides over the region’s largest telecommunications network. Several former presidents are the result of this migration; most notably Michel Temer, the former president of Brazil and the son of Lebanese migrants. Temer’s parents were peasants from Btaaboura—a typical Lebanese small village about an hour north of Beirut—who came to Sao Paulo in 1925. There are other cases of heads of states and vice presidents such as:

- Argentina’s President Carlos Menem from 1989–1999 (born to Syrian parents)

- Ecuador’s President Abdalá Bucaram from 1996–1997 (father was the son of Lebanese immigrants) and President Jamil Mahuad from 1998–2000 (father traced his roots to Lebanon)

- El Salvador’s President Elías Antonio Saca from 2004–2009 (father traced his roots to Palestine) and Nayeb Bukele from 2019–present (paternal grandparents were Palestinians from Jerusalem and Bethlehem)

- Honduras’s President Carlos Flores Facussé from 1998–2002 (mother was of Palestinian descent)

- Colombia’s President Julio César Turbay from 1978–1982 (born to a Lebanese father)

- Paraguay’s Mario Abdo Benitez from 2018-present (father was of Lebanese descent)

- Venezuela’s Vice Presidents Elias Jaua from 2010-2012 (father was of Lebanese descent) and Tareck Zaidan El Aissami from 2017-2018 (born to a Druze Syrian father, and a Lebanese mother; also the great-nephew of Shibli al-Ayssami, former Vice President of Syria and Deputy Secretary-General of the National Command of the Iraq-based Ba’ath Party)

In some cases, you can barely differentiate the Arab names from Latin-sounding ones—many adapt Latin-sounding first and middle names, and very often the spellings for their last names are latinized so that they better adapt to the sounds of the Spanish-Portuguese alphabet. Some others simply lose the Arab last name due to intermarriage. For example, Debbie Mucarsel-Powell—the spelling of “Mucarsel” in Lebanon is “Moukarzel”—a former congresswoman (D-FL) was an immigrant from Ecuador and of Lebanese heritage.

There is a perception that the success of many of these Arab American communities in Latin America is due to the welcoming homes and valuable connections made through the existence and popularity of “Centros Arabes” or “Club Arabes.” These multireligious Arab social and networking clubs—they often contain a restaurant, pool and garden, and hall to host events—are also widely popular in the Middle East. These communities were present in most cities and even towns with significant Arab communities such as Argentina, home to “Confederacion de Entidades Argentino Arabes,” which links more than 150 Arab community groups across the country.

According to Lamia Oualalou, a Mexican journalist of Arab descent, orientalism was “reinvented” by these Arab communities in Latin America by embracing aspects that were highly attractive and acceptable to the local population in order to negotiate their differences: i.e. belly-dance. Belly dancing became a tradition for the Arabs of the Latin American continent, allowing these communities to integrate skillfully and have a significant role in yearly local traditions like Carnival. Another example is the song Allah-la Ô, written in 1940 by David Nasser and Antônio Nássara, who are descendants of Lebanese immigrants. As Lamia explains, the song “evokes the nomadic life of the caravan, the desert, and Islam, set to a samba rhythm. It’s still a classic.”

What the data tells us: the US numbers are actually tiny

Today, Brazil is home to the largest community of Arab descent in the Americas with an estimated population of seven to twelve million (some other estimates range from twelve to fifteen million) or 3.5-6 percent of the population. Habib’s the largest Arab fast-food chain with 475 outlets, also resides in Brazil. In contrast, according to the Arab American Institute, the Arab population in the US is 3.6 million (not counting Latin Arabs) or roughly 1 percent of the US population. However, the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey in 2019 estimates those with Arab Ancestry to be at 2.1 million—a lower figure partly due to the limits on the ancestry question. In Spanish America, Argentina has received the most Arab immigrants (about 4.5 million), followed by Mexico, Colombia, and Venezuela (1.5-1.6 million each). Interestingly, Venezuela also has the largest Druze community outside of Syria, Lebanon, and Israel, whereas Chile has eight hundred thousand Palestinians—the largest Palestinian community outside of those in Israel, Lebanon, and Jordan.

It is a good reminder that this Arab community in Latin America is the closest counterpart to Arab Americans in the US—who are often becoming US citizens and already referring to themselves as Americans. Among the most significant differences between the two communities is perhaps the tendency for those in Latin America to refer to themselves as Brazilian or Argentinian rather than “Arab-Brazilian” or “Syrian-Argentinian.” This may be because the US is by far the largest melting pot of immigrants. And, although there are many parallels, the Arab community in Latin America has had the chance to take on leadership positions such as president and vice president, thereby impacting the national discourse on Arab heritage and what is possible for the Arab community.

This achievement can be seen as an example of immigration and integration to many. This is partly due to the multireligious and multiethnic “Centros/Club Arabes” that has allowed many to remain tied to their history and culture while also taking part in a completely new national identity. Many of these communities have also moved to the US and become increasingly confused when filling out government forms and checking a box for classification purposes. Still, they can find a sense of home in both the Latino and Arab communities, continuing to shape the melting pot that makes the United States such a unique place.

Joze Pelayo is a program assistant at the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative/Middle East Programs. Follow him on Twitter: @jozemrpelayo.

Image: Shakira performs onstage during the Pepsi Super Bowl LIV Halftime Show at Hard Rock Stadium on February 02, 2020 in Miami, Florida. Photo by Lionel Hahn/ABACAPRESS.COM