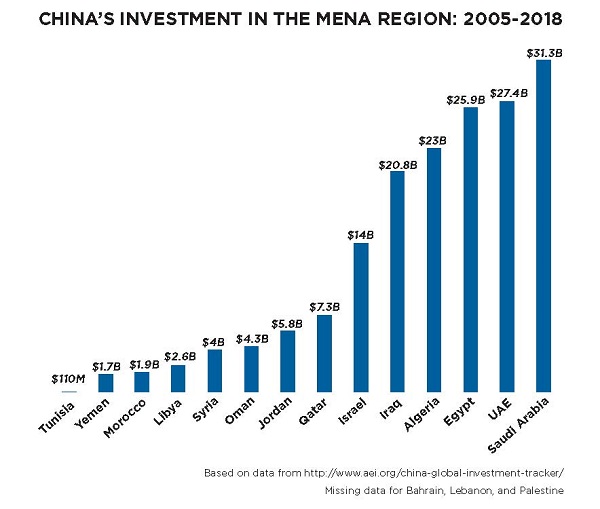

China’s overall strategy to increase its role in world affairs indicates further engagement in its global investments in Asia, Africa, and beyond. It holds the most foreign reserve assets in Asia and is the largest trading partner in Africa. However, China is also continuing to diversify its portfolio by adding investments in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Although these investments are significantly smaller, Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the MENA region is growing rapidly. Since 2010, China invested billions of dollars in nearly every MENA country and in 2016 eclipsed the United Arab Emirates to become the leading investor in the region.

China’s surge in investment is underpinned by the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum (CASCF) and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also known as the Silk Road Economic Belt. The CASCF is a formal dialogue initiative that promotes various types of cooperation, including economic and trade exchanges. The BRI is a major trade and infrastructure project that links some seventy one countries—with high-speed railroads, gas and oil pipelines, and motorways—to promote and facilitate global trade. It includes several proposals to stimulate cooperation between China and MENA countries. Within the BRI, the China-Central-West Asia Economic Corridor (CCAWAEC) and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) offer the most direct routes for China-MENA trade.

Sources: International Road Transport Union, Brookings, Council on Foreign Relations

In many ways, China’s interest in the MENA region is purely economic in nature: the region plays an important role in the BRI, and China relies on energy resources from the Middle East. As the world’s most populous country with the second largest economy, China has enormous energy demands; China’s National Bureau of Statistics reported that China’s energy consumption totaled 4.48 billion metric tons in 2017, more than every European Union country combined. China is the world’s top crude oil importer, and much of its crude oil comes from the Middle East. In 2018, Saudi Arabia was the second largest supplier of crude oil to China, and Iraq was the third largest supplier.

China’s interest in the MENA region is also driven by the belief that economic development can contribute to mitigating certain security problems. The region’s economic performance is severely impacted by terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (ISIS) in countries like Libya, Iraq, and Syria, as well as long and violent wars like the ongoing Syrian and Yemeni conflicts. The region is also plagued by the misuse of government wealth by corrupt and ineffective leaders. For example, Iraq has experienced widespread unrest over poor public services and job prospects, exacerbated by graft.

China sees similar security problems within its own borders. Terrorist groups like the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) continue to grow in size, and there is a persistent widening of socioeconomic rifts along ethnic lines. In response, China not only increased security personnel in the province, but also enacted economic practices meant to bolster lower-income regions and stimulate economic growth. These efforts are meant to mitigate violent uprisings from aggrieved populations.

China’s foreign investment strategies reflect its domestic policies. When Western powers lifted sanctions on Iran in 2016 after the implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), President Xi strengthened diplomatic ties with Iran’s leaders and promised to increase bilateral trade to $600 billion over the next ten years. It is unclear how the US withdrawal from the JCPOA in May and reinstatement of sanctions on Iran on August 6 will affect this investment.

Additionally, despite the ongoing Syrian civil war, China is maintaining its investments in Syria, but at a fraction of its investment across the region. China became a 35 percent stakeholder in Syria Shell Petroleum Development (SSPD) in 2010; which is a subsidiary run in Syria and operated by Shell. SSPD held a 31 percent stake in al-Furat Petroleum Company, and operated three production licenses in one of Syria’s biggest oil conglomerates; until it was sanctioned by the European Union in December 2011. It is set to potentially invest in Syria’s reconstruction, renewable energy, and healthcare. According to Qin Yong, the Vice President of the China-Arab Exchange Association, Chinese companies are eyeing projects to rebuild Syrian infrastructure and industry across the country.

More recently, China opened a new chapter in Sino-Arab relations by pledging $23 billion in loans and financial aid to MENA countries. Loans totaling $20 billion aim to facilitate economic and industrial reconstruction in the Middle East, as well as cooperation on oil, gas, and nuclear energy. China will set up a consortium of Chinese and Arab banks, with a dedicated fund of $3 billion. Finally, China is expected to give an additional $15 million to Palestinians for economic development and $90 million in aid to Syria, Yemen, Jordan, and Lebanon. China has not provided details on when or how the money will be dispersed, and the overall relationship between the consortium, loan package, and financial aid is also unclear.

By 2020, China aims to reach a $600 billion trade aggregate with the Middle East. Undoubtedly, this will be a boon to some countries. Other countries, however, have expressed concern about China’s expansionist ambitions. The United States potentially has the most to lose. Projects like the BRI suggest that Beijing has the desire to augment its growing economic and strategic influence with a “soft power” narrative that presents China as an alternative leader to the global hegemony of the United States. Essentially, China is continuing to use financial mechanisms to become an international player deeply embedded in the MENA region’s geopolitical landscape. As China moves forward with its own agenda, its MENA investments should be closely monitored.

Aisha Han is an intern at the Rafik Hariri Center at the Atlantic Council.

Rachel Rossi is an intern at the Rafik Hariri Center at the Atlantic Council.

Image: Photo: Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and Saudi Arabia's Foreign Minister Adel bin Ahmed Al-Jubeir arrive for a news conference at a China Arab forum in Beijing, China, July 10, 2018. REUTERS/Thomas Peter